How Myra Breckinridge became Raquel Welch's wildest movie role

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Raquel Welch, who died Wednesday at age 82, will likely be remembered as one of the greatest sex symbols of the 20th century — the image of her clad in a fur bikini from 1966's One Million Years B.C. launched her to international stardom.

But just four years later, one of the most interesting and downright bizarre products Hollywood ever unleashed on the world nearly ruined her career.

Based on Gore Vidal's acclaimed 1968 novel of the same name, 1970's Myra Breckinridge starred Welch as a transgender woman who tries to subvert gender norms and dismantle the Hollywood patriarchy — while looking great doing it. The film brought cinema legend Mae West out of retirement, marked the film debut of Tom Selleck (as one of West's himbos), and was Farrah Fawcett's second appearance on the big screen.

Everett Collection

The plot goes something like this: Myron Breckinridge (played by noted film critic Rex Reed, with the caveat that he refrain from writing about the film during production) flies to Copenhagen to have a gender affirmation surgery, or as they called it back then, a sex change. Returning as the beautiful Myra (Welch), she tracks down her uncle, Buck Loner (John Huston), and claims to be the widow of the late Myron. Loner, a conservative former Western star and the proprietor of an acting school, is skeptical but agrees to give Myra a teaching job to help her make ends meet.

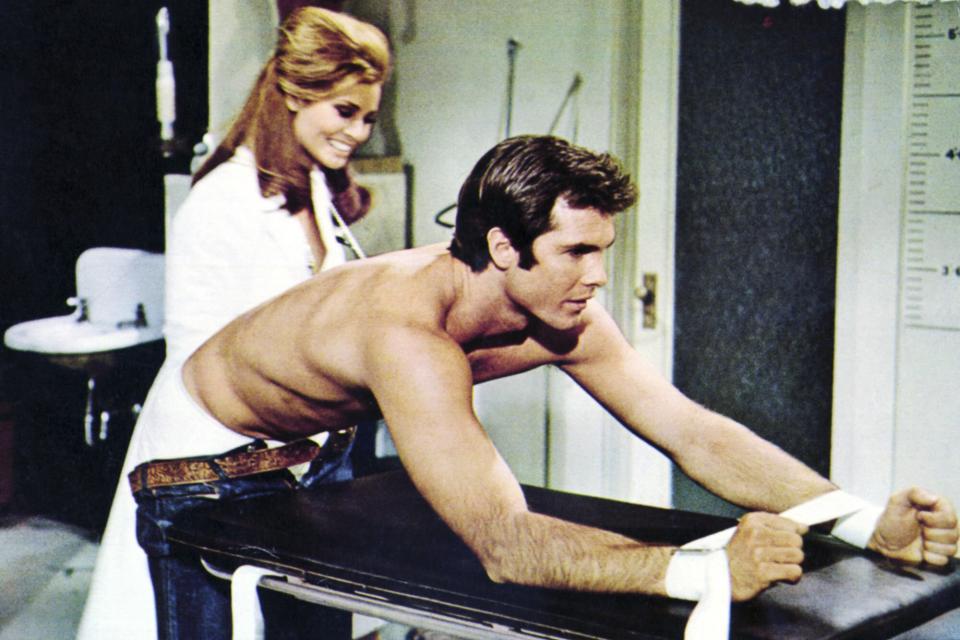

Myra is supposed to teach a simple class on etiquette, but instead uses the opportunity to deconstruct the social order of the Golden Age of Hollywood and introduce dominatrix practices into the curriculum. She goes on a well-coutured tear through the campus, seducing a pair of lovers she believes embody traditional gender norms: the macho Rusty (Roger Herren) and the submissive Mary Ann (Fawcett).

Over the course of her shenanigans, Myra converses with a physical manifestation of Myron, revealing her ultimate plan is "the destruction of the last vestigial traces of traditional manhood in the race in order to realign the sexes, thus reducing population while increasing human happiness and preparing for its next stage."

Everett Collection

In one of the film's many controversial scenes, Myra rapes Rusty with a strap-on, which in turn causes him to break up with Mary Ann, leaving Mary Ann freed up for Myra's advances. Myra's sexual appetite is juxtaposed with that of glamorous, singing, wise-cracking casting agent Leticia van Allen (West), who seduces many young actors seeking an audition.

Eventually, Uncle Buck finds out that there's no death certificate for his nephew Myron and confronts Myra, who then strips naked in front of her horrified uncle, revealing, shall we say, the last vestigial traces of her traditional manhood. After this revelation, and Myra's continued seduction of Mary Ann, the Myron manifestation runs Myra over with a car, claiming she had become too ambitious. Myron then awakens in the same Copenhagen hospital, admitted not for a sex change, but for a car accident, with Mary Ann as his attending nurse — as if it was all some sort of dream or hallucination.

In 1970, the entire film must have felt like a hallucination. Myra Breckinridge was one of several movies given an X rating, including that April's Best Picture Oscar winner, Midnight Cowboy. Another was the Roger Ebert-penned Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, which was also critically derided upon its release. Sentiment has softened for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, now a certified camp classic, but Myra Breckinridge hasn't quite attained the same status. But if the onscreen hijinks were wild, the production was a circus.

Everett Collection

Vidal's novel was a hot property in a Hollywood giddy over its new, relaxed movie rating system, which made room for more adult fare at the box office. Twentieth Century Fox bought the rights for $750,000, paying the author an additional fee for writing the first draft of the script. Studio head Richard Zanuck didn't care for Vidal's draft and hired TV writer David Giler to turn in another one. Vidal liked Giler's version, but that mutual good feeling didn't last for long.

According to TCM, both Audrey Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave turned down the lead role of Myra, while Elizabeth Taylor, Anne Bancroft, and Angela Lansbury were also under consideration. In an alternate reality, there's a version of Myra Breckinridge starring Angie Lasnbury and I'm ready to Everything, Everywhere All at Once myself to see it immediately. In what would have been a uniquely prescient Hollywood casting decision, Andy Warhol superstar and actual transgender woman Candy Darling fought to play the role of Myra, albeit unsuccessfully.

That "honor" went to Welch, who campaigned extensively for the role, hoping it would change her image as a sex symbol and bring her credibility as a serious actress. It definitely did not do the latter. Instead, she had to contend with both a costar (West) and director (Michael Sarne) from hell. According to TCM, Sarne referred to her as an "old raccoon" and told her she had only been cast as a joke. Welch reportedly spent much of the production in her dressing room, crying.

Sarne had replaced Bud Yorkin, co-creator of Maude and All in the Family with Norman Lear, but the studio feared his version of the film would be too tame. Desperate to appeal to the kids, producers chose Sarne, who'd just scored a small cult hit with 1968's Joanna. Sarne's contract stipulated he couldn't be fired before turning in the first cut of the film, and he used that stipulation to alienate the entire cast and crew.

Sarne, however, got along famously with West, whom he suggested for the role of Leticia van Allen after an appalled Bette Davis turned it down. West hadn't appeared in a film in 27 years, but on advice from a psychic, met with the young director who convinced her to make a triumphant-ish return.

Everett Collection

West agreed to do the film, with a number of stipulations: She would be paid $350,000; she could write her own dialogue; she would have a 5 p.m. start time; she would have two musical numbers, despite the film not being a musical; the character's name would be changed from "Letitia" in the book to the "tit"-less "Leticia"; and she would get approval over not only her wardrobe, which would be designed by the legendary Edith Head, but also Welch's. Each day she showed up to the studio surrounded by young, muscular men.

West, perhaps threatened by the sex symbol du jour Welch, was reliably unfriendly to her younger costar. In interviews, West would refer to Welch as "Rachel Woosh," "Rock Walsh," or a variation thereof, and once quipped of Welch's casting, "Of course, no real woman would play this part." The two women never shared a single frame of the film, despite appearing in the same scenes.

Sarne reportedly spent up to seven hours at a time just thinking, while holding up production. He once spent eight hours photographing a cake. He didn't want to do the film, hated the novel, and thought Vidal would make the film "too gay." He referred to Huston, an esteemed filmmaking veteran, as a "decrepit old hack," mistreated Welch, and constantly re-wrote the script, leaving the narrative all but incoherent. Inevitably, Zanuck shut down production, forcing Sarne to crib together whatever he had.

Everett Collection

The final product was, unsurprisingly, universally loathed. Time said it was "about as funny as a child molester." Vidal outright disowned it. Myra Breckinridge, made on a budget of $5 million, grossed $4.5 million. Sarne's name became anathema in Hollywood. Vidal, never one to hold a grudge, once wrote that Sarne had been reduced to working in a pizza parlor, calling it proof that God exists.

Perhaps the wildest part of this whole story, however, is that the U.S. government demanded scenes of then-ambassador Shirley Temple be removed from a montage of classic film stars intercut with Myra's rape of Rusty. Loretta Young also successfully sued to have her scenes removed.

Yet despite its controversy and nearly unparalleled ignominy, Welch seemed to warm to the picture in her later years.

"The making of the movie was fun, in a kind of a way," the actress told Out magazine in 2012, in anticipation of a retrospective of her films, including Myra Breckinridge. While she thought the film paled in comparison to the book, which she thought was "so extraordinary," Welch had kind words for Sarne, calling the way he told the story and developed the premise "clever and witty and entertaining." Of West, Welch said she didn't think the screen legend was "very happy on that set" but gave her the ultimate Hollywood seal of forced ambivalence: "She was something...."

Ultimately, though, Welch was kind of proud of having made what Leonard Maltin called "as bad as any movie ever made."

"I'm so very glad I made it," she told Out, "because I think it means that someday, someone somewhere will have the cojones to come along and really do it the way Gore intended it. And make it the funny, erudite movie it really should be."

Related content: