‘There’s Some Music Coming Out of the Bronx Called Rap,’ How the Village Voice Championed Hip-Hop and Changed Criticism

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

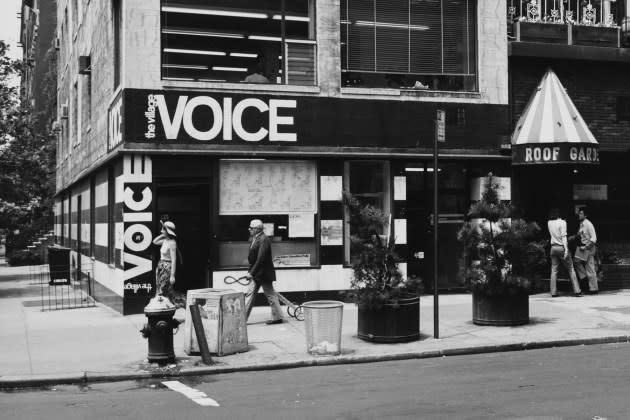

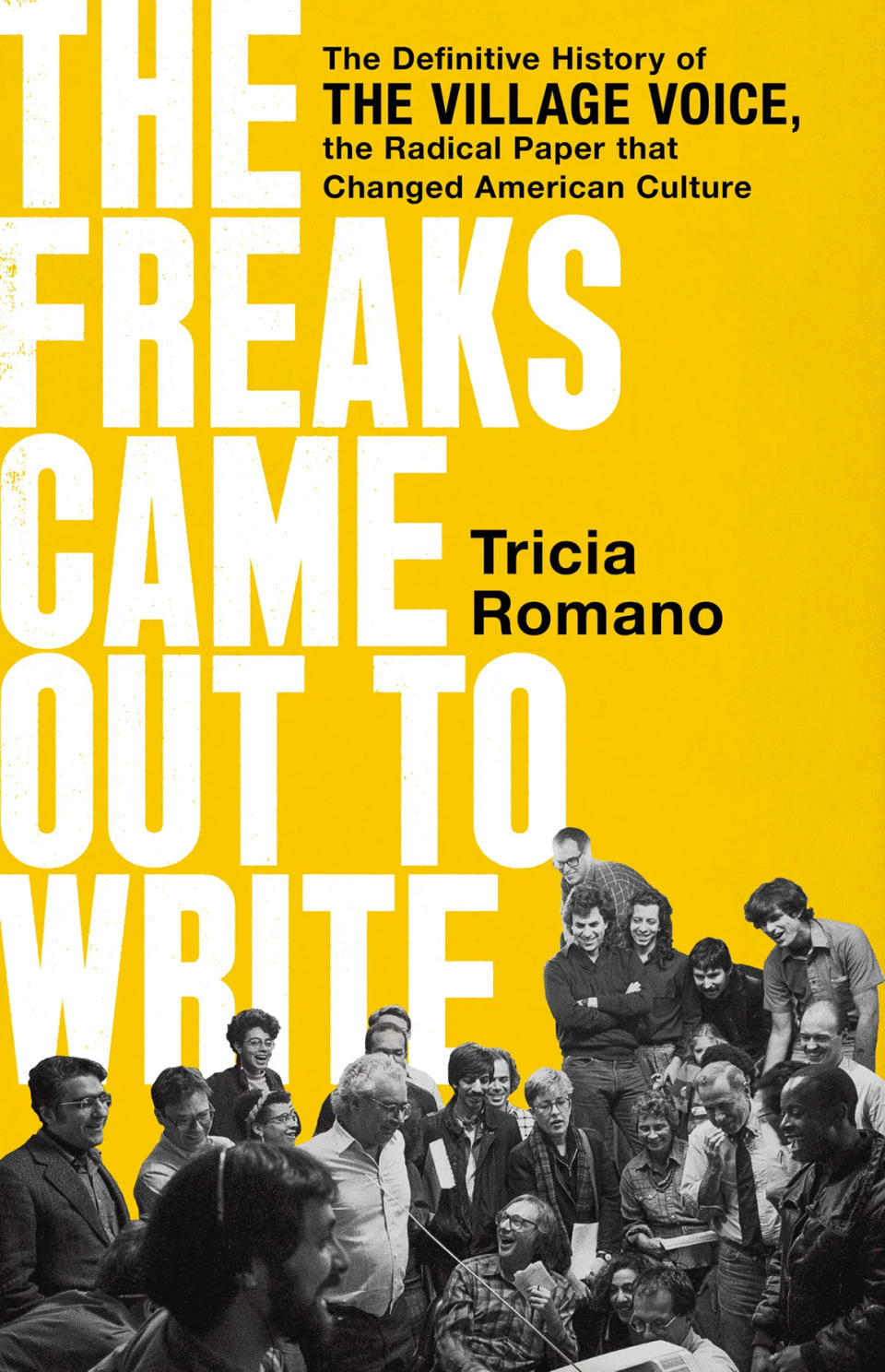

Almost immediately after its founding in 1955, the Village Voice became the most raucous, irreverent and important alternative newspaper in America. At one point the Voice was the most read weekly in the country, serving as Andy Warhol put it “the entire liberal thinking world.” In her excellent new book The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture, Voice veteran Tricia Romano has compiled an oral history of the seminal alt-weekly. Romano’s book is a vital and wildly entertaining read — documenting six decades of American life from the cultural heart of New York City. (Sample chapter title: “We’re against gentrification, and we’re for fist-fucking.”) In this exclusive excerpt from ‘Freaks Came Out to Write,’ Romano recounts the Voice’s pioneering coverage of a musical genre coming out of the Bronx in the early ’80s and the paper’s irascible and brilliant music critic Robert Christgau, who helped shape music writing for a generation.

BARRY MICHAEL COOPER: I had this conversation with Bob Christgau in January of ’80. I said, “There’s some music coming out of the Bronx called rap music. This is going to be a game changer.” He said, “I don’t believe that.” I said, “I’m telling you, there’s a group called Funky 4 + 1 — these four guys, a girl who’s a rapper, Sha-Rock. They got a record called ‘That’s the Joint.’ This thing is phenomenal.” And two days later, he called me to come down to the Voice. “You were right. This is something.”

More from Rolling Stone

VINCE ALETTI: I was at Tower Records. I was a buyer there, but I also started writing occasionally at the Voice with Bob. My first real editing job was when Jeff Weinstein took a three-month break, and I filled in for him as the art editor.

God knows how it became me — well, I wrote one of the first pieces for Bob about hip- hop. I reviewed a hip-hop concert that was at what’s now Webster Hall.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU: We were covering hip-hop before anybody except for the Amsterdam News. Robert Palmer, who had been at the Times, was not insensible to how good hip-hop was, but we did more of it. I certainly am not going to be so modest to suggest that some other music editor would have been as quick on it as I was. I was very quick on it.

GREG TATE: Bambaataa used to be the DJ for the Village Voice Christmas party for about six or seven years running. Bam really knew how to promote hip-hop as a thing. He knew the value of the press.

It was such a small world then. Everything happening in New York was happening below 23rd Street to Canal. On Fifth Avenue, it was Peppermint Lounge, Danceteria, and then on down, CBGB’s, and then Mudd Club. Everything that mattered in culture was happening in the East Village, about the twenties on down, east and west.

The first hip-hop show I went to was one that Bob asked me to review, a midnight show at the Ritz. I was still living in DC. He wasn’t paying for a hotel. I took the Amtrak up and then took the Amtrak back after the show. It was for a group, the Fearless Four doing “Rockin’ It,” one of the great one-hit wonders of early hip-hop.

CAROL COOPER: In the mid-’80s, the level of hip-hop writing that new Black writers were bringing into the Voice was intense. And part of that was because Robert Christgau loved hip-hop. He loved hip-hop more than he ever, ever loved house or any other marginal music. So, the combination of his editorial support, and a bunch of new writers that he was cultivating who were similarly enthusiastic about it, makes hip-hop a natural pivot point. The amount of writing that we did on world music was equally significant.

NELSON GEORGE: In ’81, I got my first real job at Record World. Sometime in that year, I sold him a piece about Lovebug Starski, an early rapper. Then I sold them another short piece on Grandmaster Flash. That was the beginning of my relationship with the Voice.

BARRY MICHAEL COOPER: Greg Tate and Nelson George became a paradigmatic shift, not only at the Voice but in writing and journalism, period. I couldn’t hold their Gatorade. They were — and still continue to be — two of the greatest writers that came out of the Village Voice, and the Village Voice is filled with great writers.

Nelson was critical theory, period, all the way down the line, talking about Black bohemians, talking about hip-hop, and Nelson’s way of contextualizing things made all the difference. He made you really, really sit down and think about Public Enemy, about Russell Simmons, about hip-hop — and from top to bottom, from the basement to the penthouse, he would give every layer of what his subject matter was.

Nelson George: I made it my mission to write about R&B artists. That particular branch of Black music was really atrophying. Tate was really interested in jazz and avant-garde jazz. Barry was interested in funk and different kinds of hip- hop, but also keyboard-driven funk. And then I was really interested in mainstream R&B, which I always felt never got any respect. Carol Cooper was also interested in reggae and Latin music.

GREG TATE: We’re all about the same age. We had it covered from three different sides. We never really tripped over each other.

NELSON GEORGE: It was amazing that Bob could edit all of these different people. He also was editing Stanley Crouch. See, because Stanley Crouch was musicological, elevated, “I’m telling you what the real shit is.” And Tate is really in his “Ironman” phase, so he’s writing crazy, psychedelic shit. I’m like white bread in there, just trying to get my shit in there.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU: I tell people Nelson used to write on the fucking subway. People would see him sitting there on the subway scribbling in his notebook.

NELSON GEORGE: I had some writing skills, but Bob taught me how to think about making an argument. And not just to write about lyrics, which is one of the things that was wrong with rock criticism, was that it was all about lyrics, and not enough about music. And Black music was about music. If you weren’t writing about syncopation or polyrhythms or how bass and drums interact, then you really weren’t writing about the music. You were just dancing around.

RICHARD GOLDSTEIN: There’s this whole tradition of white liberals writing about Black music that goes back to jazz— Hentoff, Leonard Feather— and they didn’t do a bad job, they introduced the music to the public, but the fact is, they weren’t Black. The Voice really pioneered this school of expressive Black writing— almost coming close to postmodernism.

VERNON REID: The Voice had actual Black writers writing about Black art. That was a big deal. That wasn’t happening at the New York Post and the Daily News. The Village Voice actually had Black writers writing about Black stuff, writing about Basquiat and writing about Spike Lee and writing about Chris Rock, you know? They were writing about just- emerging, talented people, and that was important.

Much of the credit for the Voice’s pioneering coverage belongs to Robert Christgau, the “dean” of music criticism. Christgau’s Consumer Guide practically invented the capsule review. The tight and precise writing became essential reading for music fans and helped set the industry standard for criticism.

“An A+ record is an organically conceived masterpiece that repays prolonged listening with new excitement and insight. It is unlikely to be marred by more than one merely ordinary cut.

An A is a great record both of whose sides offer enduring pleasure and surprise. You should own it. . . .

E records are frequently cited as proof that there is no God. . . .

An E– record is an organically conceived masterpiece that repays repeated listening with a sense of horror in the face of the void. It is unlikely to be marred by one listenable cut.”

— Christgau’s Record Guide: Rock Albums of the ’70s (1980)

ERIC WEISBARD: The Consumer Guide is one of the great masochistic acts of criticism ever perpetuated.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU: The idea was that there is more “product,” let’s call it, than there is space and time to write about it. I decided I would call this column where I did these capsule reviews of records the Consumer Guide, and that I would do another thing that hippies weren’t supposed to do and offer letter grades at a time when pass/fail was at its peak. It was just a way to be contrarian.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU, CONSUMER GUIDE, VILLAGE VOICE, 1980:

Prince, Dirty Mind (Warner Bros., 1980)

After going gold in 1979 as an utterly uncrossedover falsetto love man, he takes care of the songwriting, transmutes the persona, revs up the guitar, muscles into the vocals, leans down hard on a rock-steady, funk-tinged four-four, and conceptualizes — about sex, mostly. Thus, he becomes the first commercially viable artist in a decade to claim the visionary high ground of Lennon and Dylan and Hendrix (and Jim Morrison), whose rebel turf has been ceded to such marginal heroes-by-fiat as Patti Smith and John Rotten-Lydon. Brashly lubricious where the typical love man plays the lead in “He’s So Shy,” he specializes here in full-fledged fuckbook fantasies — the kid sleeps with his sister and digs it, sleeps with his girlfriend’s boyfriend and doesn’t, stops a wedding by gamahuching the bride on her way to church. Mick Jagger should fold up his penis and go home. A

COLSON WHITEHEAD: He’ll pack so much into those five-line reviews. He knew everything. I didn’t always agree. I didn’t know what he was talking about half the time, but the stuff he liked, he really championed and made me want to buy it.

CHUCK EDDY: I don’t know how many people over the years have told me that Christgau is unreadable. I understand that — my ticket into being interested in people writing intelligently about music was figuring out what the hell Christgau was talking about.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU: I didn’t want to be a rock critic. My idea was to be a journalist. My ideal was A. J. Liebling. I love sportswriting in general. Some of the sportswriters were great writers. I was a baseball fan; baseball fans love charts and statistics. So, I kept rock ’n’ roll statistics. I worked for an encyclopedia company in ’64. That taught me compression.

FRANK RUSCITTI: Christgau was hated by bands because he was so honest, and he was so brutal. There’s a single out there, I forgot who did it, called “I Killed Christgau.”

I don’t know why

You wanna impress Christgau

Ah let that shit die

— “Kill Yr Idols” (aka “I Killed Christgau with My Big Fuckin’ Dick”), Sonic Youth

CLEM BURKE: A lot of people would take an antagonistic attitude toward Christgau, but I always thought he was pretty right on and honest in his views and very credible.

ROBERT CHRISTGAU, CONSUMER GUIDE, VILLAGE VOICE, JANUARY 29, 1979

Lou Reed, Live: Take No Prisoners (Arista, 1978)

Partly because your humble servant is attacked by name (along with John Rockwell) on what is essentially a comedy record, a few colleagues have rushed in with Don Rickles analogies, but that’s not fair. Lenny Bruce is the obvious influence. Me, I don’t play my greatest comedy albums, not even the real Lenny Bruce ones, as much as I do Rock n Roll Animal. I’ve heard Lou do two very different concerts during his Arista period that I’d love to check out again— Palladium November ’76 and Bottom Line May ’77. I’m sorry this isn’t either. And I thank Lou for pronouncing my name right. C+

Critics! What does Robert Christgau do in bed? You know, is he a toefucker?

— Lou Reed, Live: Take No Prisoners

RJ SMITH: Steve Anderson was his intern and would open his mail at home. Bob had panned the Swans— noise, East Village, dirge-y, Michael Gira, droning, pretentious, whatever. He slammed them in a Consumer Guide. So, Michael Gira jerked off in a baggie, sealed it up, and mailed it to Bob with an angry letter — or witty letter, he would probably think. Bob opens it, reads the letter himself, pulls out a bag of cum, and he hands it to Steve and says, “OK, file this under G.”

James Wolcott started as a music writer and was writing for Bob. Somewhere along the way, they started sniping at each other through print. At least, Wolcott took shots at Bob, and then Bob started writing about his sex life a lot and problems he and Carola were having, and then Wolcott weighed in on it at least once, and talking about putting up bleachers and having people watch them have sex. That was the classic Village Voice arguing with itself in public. It’s what we had instead of getting paid well.

GREG TATE: He got really interested in feminism and sex, and he would write these pieces where he would be talking about his own sex life. In one of them he said something like [laughs], “I’ve been fucking the same woman for twenty years, and hopefully I’ll be fucking her until she dies.” Like, “Not till we die.” [Laughs.]

DAVID SCHNEIDERMAN: We didn’t have the money for everyone to have a computer then. One day, Bob is complaining that at four o’clock, when he wants to do his work, the computers are taken. I said, “Bob, when I come in in the morning, for hours no one’s on these computers.” Bob puffs up and says, “I will not change my diurnal urges.”

NELSON GEORGE: You’d go to Bob’s apartment, and the place is crazy: a warren of records everywhere, and clothes, and you had to duck to get down the narrow hallway. And then he had that little office, which is legendary. There’s five records on the turntable playing at any given time, all stacked up. Ornette Coleman, then the sounds of West Africa, then a blues band from England, and then, you know, Olivia Newton-John. And they just come one after another while you’re in there trying to edit with him at his little typewriter.

He and his wife were so lovely. When they were trying to have a kid, you could only edit with him during certain times. It was like, “She’s ovulating.” Bob always gave you a little more information than you wanted.

RJ SMITH: I was to bring my story over to his home. I knock on the door. He buzzes me into the building, comes to the door on the second floor. He’s in his underpants with a garbage can, like, right in front of where I’m glad he had a garbage can. And he said, “Put it in the garbage can! Just put it in the garbage can! Quick, quick!”

RJ SMITH: If Bob had never become a writer, never done the Consumer Guide or anything, and was just an editor, he still would be such an influential figure.

GARY GIDDINS: We became great friends, and he’s the best editor I’ve ever worked with. I learned so much about writing from him. Every time I handed in a piece, I walked away knowing something I didn’t know before. And he liked working with me because he never had to tell me anything twice.

NELSON GEORGE: He was incredibly blunt, so you’re a little scared, but at the same time he was incredibly nurturing once you got past the bluntness.

CAROL COOPER: He was an obsessive line editor. Which meant that at the early stages of working with him, if you were used to the places that left your copy more or less alone, it could be either annoying or humbling, depending on how you felt about it, that he would want you to change almost every other word in something you had already worked on for a week.

COLSON WHITEHEAD: I actually had only one Christgau edit, and it was over the phone. I thought I missed out. But my then girlfriend, Natasha Stovall, was an interim music editor, so, he did Pazz & Jop in our house in Fort Greene in January of ’97. It was like Jesus had come to my apartment. Like, “Oh my god, Christgau’s in my house.”

JAMES HANNAHAM: My mother was dying of Alzheimer’s. It took her a very long time to get through it, and I was panicking. People were offering sympathy without help. Bob took me to lunch, and he gave me the name and number of an eldercare lawyer. He was one of the only people who just did something. It was so small, but it meant so much to me that I feel forever indebted to him for just this one little gesture.

GARY GIDDINS: I remember one guy saying, “You know, people are going to be writing books about Bob.” And we all knew what he meant, because Bob is a character. He called himself the dean of rock critics.

I was still writing movie reviews at the Hollywood Reporter. And there was a movie called Looking for Mr Goodbar. Remember that? Diane Keaton. It was a pretty bad movie. And Bob walked in — this is when he had this long, straight hair that went down his back — and he walked in very briskly, like, “I’m here — you can start the film!”

And at one point, the Diane Keaton character says something like, “How can you really understand or come to grips with reality?” And Bob said, “Well, for a start, you could stop watching this film!” We all just fell out.

“Excerpted from The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture by Tricia Romano. Copyright © 2024 Tricia Romano. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Book LLC., a publishing group of Hachette Book Group, Inc. New York, NY, U.S.A. All rights reserved.

Best of Rolling Stone