‘The Movie Man’, A Kind Of Canadian ‘Cinema Paradiso’ And Underdog New Documentary For Film Lovers, Tries To Find Its Way Into Fall Festivals – TIFF And Telluride, Are You Listening?

EXCLUSIVE: The major fall film festivals — Venice, Toronto, and Telluride especially — may be fearing more by the day that the current combined WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes are going to put a serious crimp in their plans for glorious, star-filled fests that also can have an impact in launching awards season (just today, MGM said Zendaya’s Challengers withdrew as the Venice opening-night film and its release moved to late April 2024 due to the actors strike).

With the clock ticking and August just around the corner, these fests have to start planning what life will look like without the buzzy boost of A-list stars and a feeling by distributors and studios that maybe they ought to second-guess current (as yet mostly unannounced) participation with their awards-bait films that could be moving all over the release map. Following the pandemic shutdowns, these festivals got their mojo back last year, and appeared to be headed toward a full return to normalcy — that is until the picket signs came out.

More from Deadline

Well, I have a suggestion, particularly for Toronto and Telluride, in case they find themselves in need of something new, unaffected by the strikes, that just might become the kind of crowd-pleasing word-of-mouth hit these fests love to “discover” and shepherd through the world.

The other day I got a look at a work-in-progress (final audio mix was just completed yesterday) that is the kind of off-the-radar movie that gives me hope for movies beyond all the pandemics, strikes, layoffs, Wall Street forecasts, theater bankruptcies and on and on. So what is it? A documentary five years in the making about one guy deep in the forest of a tiny Canadian town desperately, and singlehandedly, trying to keep his movie theatre alive against all odds. It is called appropriately enough, The Movie Man, and beyond being the story of this one solitary figure and maybe the most unusual movie theater on the planet, it also really is the story of the industry itself in all of its aspects, from the movies to their distribution to their exhibition to technological changes to, well, just trying to survive another season.

It comes from a Canadian filmmaker named Matt Finlin, a Toronto native whose his love for movies began at age 12 when he entered an oddball multiplex called the Highlands Cinemas and saw Terminator 2: Judgment Day, discovering not just a great film but also the experience inside a movie theatre like no other that informed his decision to not just see films, but also make them.

In concert with his day job making commercials and specialty films for his production company Door Knocker Media, which he runs with partner Karen Barzilay, Finlin has taken that early experience and delved a lot deeper into the wild story of this particular hidden cinema and its eccentric but colorful entrepreneur Keith Stata, who himself is a true character, a non-stop raconteur with something to say about everything.

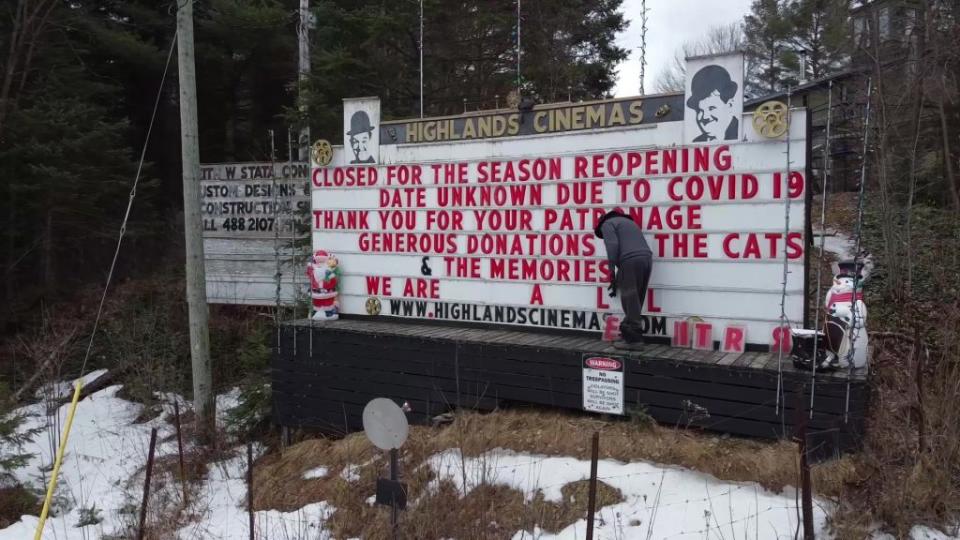

More than four decades ago, Stata, now 75, had a sort of quixotic dream of building a theater in a little town called Kinmount, which has about 200 residents and is deep in the Ontario backwoods. It’s a place that looks like it would have worked well as a location for The Last Picture Show, and has nothing to really showcase — not even a single gas station — except the ever-present Highlands Cinemas, which Stata, whose former career was in construction, expanded out from a single screen in 1979, to two, then three , then four, and now five. The theater only operates from May through Labor Day on a daily basis, and then just weekends until Thanksgiving. The rest of the year Stata has to keep it closed due to the weather; his inability to keep it staffed with young kids who go off to college (damn them); and just the problems that come with declining health, age, global pandemics and the need to keep putting butts in seats.

Oh, and did I mention he also created a one-of-a-kind movie and nostalgia museum as part of the admission price that would make the Academy jealous? Oh, and also that he has put together a world-class collection of projectors representing the entire history of theatrical exhibition (collected from Canadian cinemas)?

Oh, and Stata also has 42 cats he single-handedly takes care of and are also part of the ambience for Highlands moviegoers. If he ever sells the theater or passes it on, the cats are part of the deal. Stata is a showman in the best sense of the word, a guy who has weathered it all (literally, as we watch him shovel snow out of the way in the harsh winters), became quite sick and broke his foot, had to shut down Highlands permanently during Covid, and every year now just hopes the people will come back for one more season.

“Highlands Cinemas is one of the most unique moviegoing experiences in the world,” says The Movie Man executive producer Ed Robertson (member of Barenaked Ladies), a patron for more than 20 years. “The Movie Man is a film that captures the essence of this unique setting, celebrating its eccentric proprietor and the community that has grown around it. It is truly a love letter to the art of cinema.”

Think of it as a Canadian Cinema Paradiso. At least that is what I told Finlin when I talked with him this week. It is certainly a labor of love for this director to bring a one-of-a-kind story to the screen.

“It’s about three hours north of where I grew up in Toronto, and in the middle of nowhere, literally middle of nowhere, and we go camping and my uncle said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna go to the movies tonight.’ And it’s in a guy’s house. And you know I’m 12, and so you’re like, ‘OK’, and you drive up this road. It’s a town of 200 people as you saw, you can’t really tell what the building is and then you walk in and there it is, a labyrinth of movie memorabilia and five cinemas, and I saw T2. And it was really the inspiration to do what I do today,” Finlin told me.

So how did a whole feature documentary come about?

“My parents had bought a lake house nearby when they retired and I called [Stata] and I said, ‘Hey, I’ve been going on and off to your theater since I was a kid. I’d love to come and shoot you know, a little piece or something for something to do over a weekend’,” he says. “I didn’t know him or anything about him and and I was like, ‘Oh, I think there’s something else here.’ And so when I go to the lake house or in between working — my day job to pay the bills — I would just keep doing takes on the film,” Finlin added about the process of shooting on and off over the last few years, even through the pandemic when he thought Keith and his movie house might not survive. He stuck through it though, right up to last year when the theater, a complete mess that had to be restored, finally reopened and Stata wondered aloud whether anyone would come back — not just to his theater but to the movies themselves.

Finlin points out Stata has no family, no partner, no kids. Just him, this theater, and the cats.

“He cares deeply about them. He cares deeply about providing that experience for people that I feel like not too many people care about as much anymore which is really sad,” Finlin says. “He really, really cares about when people come in there that they are building a memory, you know, outside of the movie that they’re seeing. He is rough around the edges, but you know I really tried to dig deep and get him to share. … He is proud of the film.” (At the end we even see Stata watching it.)

“He’s proud of what he’s done,” Finlin continues. “But this summer, he’s struggling with staff and, you know, getting buns in seats is really hard at his age. Like he’s not a young guy.” Just watching him trying to transition the projection booth from film projection to digital, on the phone with an IT helpdesk, is an example of how much this really is a one-man operation.

FInlin is also proud of the musical score he got Kevin Drew, co-founding member of indie rock band Broken Social Scene, to compose. He just incorporated it into the finished cut.

“Kevin understands the power of cinema to transport people, evoke emotions, and spark meaningful conversations,” Finlin says. “As a result, his music for The Movie Man aims to capture the essence of this profound connection between Keith and the quixotic cinema he built.”

It was more than just a gig for Drew.

“As a child of going to the cinema I have watched the decline of movie theaters unfold. I find myself ashamed that I am watching more films on my phone than in the theaters as Hollywood scrambles to find solutions to keep the movie theater experience alive,” Drew said. “When I saw The Movie Man … it was such a simple and beautiful tale about the magic of going to the movies and the sadness around how cinema is dying. We are all attracted to dreamers, and this is a story of a man who acted on his dream through the passion of film and now finds himself in the modern world of how to continue. It works as a wonderful metaphor into how we need community support for dreamers and how dreamers are the ones who rescue us from the war against art.”

And so the dream continues, not just for Stata to keep his theater alive but for Finlin, who hopes to get this film out into the world, maybe at Toronto (for which he applied through Film Freeway) but even Telluride, which beyond its annual Labor Day weekend festival has itself invested in a small-town movie theater by buying the only commercial theater there, the Nugget, a single-screen old-style theater they are putting funds toward upgrading.

I can’t think of two fests that would be more perfect for a movie that has all the makings of a crowd-pleaser. Finlin fears, though, he may have missed the submission deadline for Telluride, but there are a host of fall fests out there around the country that will be scrambling amidst all the strike-related changes. He also hopes to get in one that would be an Academy qualifier. Hopefully he can. This is a movie that might have great personal appeal to a number of Oscar voters.

Says Finlin: “Keith said to me, ‘I hope you get something out of this,’ and I said, ‘I did. I mean I got to make it’. Of course it’d be amazing to get it into festivals and all these things. I want people to see it and feel the way I did when I walked in there. I wouldn’t do what I do today if I didn’t walk into that theater when I was 12 years old.”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.