‘Moonage Daydream’: How Brett Morgen Cut His Mind-Blowing David Bowie Documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When director Brett Morgen began his acclaimed David Bowie documentary, “Moonage Daydream” (Neon), he had no idea where the journey would take him. His goals were rather narrow: “I was hoping to create a theme park ride [in IMAX] around my favorite musical artist, something that would be intimate and sublime and experiential,” he told IndieWire.

“But the film became something much deeper and richer, which I didn’t expect to encounter,” he added, “because prior to starting the film, I only listened to David’s music — I hadn’t really listened to his interviews. So the film became more life affirming than I anticipated.”

More from IndieWire

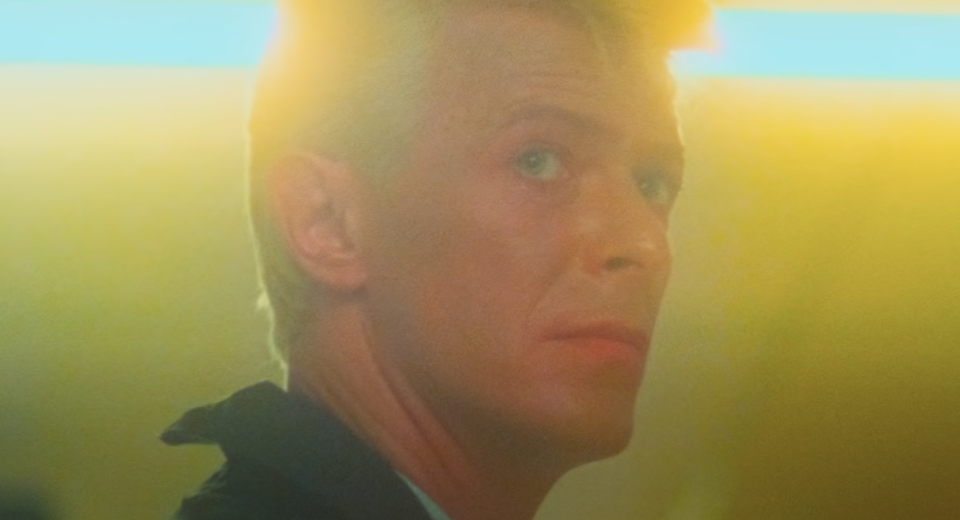

It became a kaleidoscopic, mind-blowing journey about the chameleon of rock, built around Bowie as narrator (culled from pre-existing material), performer, and philosopher about the transience of life and the promise of the new millennium. The ambitious doc is interspersed with concert footage, interviews, music, Stan Brakhage-inspired animation, sound effects, and clips from Bowie’s favorite films (including “Metropolis” and “Nosferatu”).

“Moonage Daydream” was several years in the making, with Morgen serving as his own editor for both financial and creative reasons. He spent four years assembling the film and another 18 months working on the soundscape. He first pitched the idea of an unconventional documentary to Bowie in 2007; fortunately, the project got the blessing of the artist’s estate after his 2016 passing. Morgen was granted full access to Bowie’s personal archives, which encompassed all of his master recordings and hours of discovered 35mm and 16mm film of his stage performances, including rare footage of the final “Spiders from Mars” show at London’s Hammersmith Odeon (featuring guest guitarist Jeff Beck), the Buffalo and DC shows from the 1974 “Soul Tour,” and the 1978 “Stage Tour” stop at Earl’s Court in London.

Neon

The script gave Morgen the theme of transience to build on. “When I broke that theme down into its sub-categories,” Morgen said, “I realized a lot of the [Bowie] ideas that I wanted to explore: mortality, aging, time, gender fluidity, spirituality, mobility, chaos, fragmentation. They could connect to that central theme.”

Part of Morgen’s immersion into Bowie included the building of a database concerning his creative process and taste in music, film, art, literature, and philosophy, which Morgen made use of throughout “Moonage Daydream.” But as he was finding his groove, the director faced a major crisis: he suffered a heart attack in 2017. This forced him to not only put the project on hold while he recuperated, but also look more deeply at his own life using Bowie as a role model. Spontaneity became the takeaway.

For example, in looking at a 4K scan of “The Hearts Filthy Lesson” music video — in which industrial rock meets artistic mutilation — there’s a scene where Bowie paints and dances on a stage. Morgen often listened to music while watching the archival material, and, in this case, he randomly popped in a Philip Glass orchestral piece. To his astonishment, Morgen noticed how Bowie’s movements seemed to sync up with this new soundtrack, and inserted the Glass music into an eventual scene of “Moonage Daydream.” “David was in shadow in this crouch and emerges out of it and reaches for the heavens,” said Morgen. “I can’t even say I edited it. It sort of happened.

“I remembered an interview with Michael Apted for the film ‘Inspirations,’ where David talked about his first experience with Fats Domino and the mystery of art. He didn’t understand it, but that’s what he loved about it — the mystery. It was one of those remarkable things, and the lesson from David was: ‘Yeah, that’s it — leave it alone.’ This was an example of the spontaneity that he was trying accomplish.”

But then came a creative dead end in 2018, which compelled Morgen to channel his subject even further. Bowie wrote some of his best music while traveling by train in the American Southwest in the early ’70s; following his lead, Morgen flew to Albuquerque and rode the rails back to L.A. As the train started to move, the floodgates opened. “One of the lessons I learned from Bowie was change your environment so you don’t get too comfortable and too static,” Morgen said.

screenshot/Neon

“I needed a structure and I knew this was a mythical film and David was a superhero for the alternative set,” he added. “So I was thinking a lot about Joseph Campbell and the hero’s journey.” If you view Bowie as creating his own challenges for himself, Morgen said, then his frequent collaborator Brian Eno could be seen as a Yoda-like figure, guiding him through various trials. The creative rebirth of the “Berlin trilogy” Bowie recorded with Eno — “Low,” “Heroes,” and “Lodger” — was proceeded by the addled, paranoid Los Angeles stopover that yielded “Station to Station” and Bowie’s star turn in “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” “so L.A. and Berlin became these movements,” Morgen said.

Then Morgen began the editing process. But he had to unlearn everything he had learned editorially to crack Bowie. He needed to be more spontaneous, more surreal, like one of his favorite films: Errol Morris’ “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control,” about a lion tamer, a robotics expert, a topiary gardener, and a naked mole rat specialist. Morgen happened to be in a relationship with the editor of “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control” while it was being cut; it was her first time editing a film, and her lack of experience became an asset.

“I think there was some of that naïveté that was critical to capturing that spontaneity that David expresses and talks about. But how do you put that into form? It needed to feel like a dream state. I think the fact that I’m not very refined in that realm actually was necessary to access something that would feel the dream state of Bowie.”

So Morgen would often wake up in the middle of night and cut a few hours on his Avid. That’s how he found the ending, which is a mash-up of the Bowie tracks “Memory of a Free Festival” and “Station to Station.” “That became a critical part of the experience; there was full immersion. Almost everything else was like heading into a cul-de-sac. There was fine tuning and additions and subtractions built around ebbs and flows.”

Bowie’s headlong dive into cocaine and debauchery circa “Station to Station” became another creative dead end “because there was no footage of David being really naughty, so to speak,” Morgen said. “Somehow I needed to figure out a cinematic language to convey this kind of underworld. Finally, I realized that I needed to build it, not off images of Bowie, but of Kenneth Anger and this smash up of sounds and fragrances.

screenshot/Neon

“And I found this crazy off-camera interview with David from a radio thing and when they stopped the interview, he starts riffing on fascism. He’s really high and all over the place. So I took that and mashed it with all this chaos. Suddenly I had all these other images [from the database] to pull from. That could be our way in.”

The sound design and mix (for all formats) proved integral, and Morgen wanted to especially reinvent the IMAX experience. The sound team was led by “Bohemian Rhapsody” Oscar winners John Warhurst (supervising sound and music editor), Nina Hartstone (supervising sound editor, sound designer), and Paul Massey (re-recording mixer), along with “Ford v Ferrari” nominee David Giammarco (re-recording mixer).

“There’s no orientation for the sound in terms of the front of the room and the back of the room,” Morgen said. “This film was designed to be a theme park ride so you were inside of it. So we were going to activate all of the speakers as part of the reason for the film to exist. And because of the nature of the film, the sound had to emanate from the room so you could feel it instead of hear it. The film was literally written three times: in the pre-production stage, then during the nine spotting sessions on the sound design with Nina, which then translated into the mix with Paul and David. We were working in uncharted waters and had to figure out the language. So that becomes something tenuous and a bit dangerous because everything was abstract from an editorial point of view and a sound point of view.”

Best of IndieWire

From 'Barbie' to 'Babylon,' Here's Everything Margot Robbie Has in the Works

New Movies: Release Calendar for September 2, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.