Moon’s surface ‘formed from huge impacts’ with asteroids, new research shows

Parts of the moon’s crust formed in the fiery aftermath of an impact with a huge asteroid or comet, according to new research.

Analysis of moon rocks collected by the Apollo 17 mission in 1972 show that the rock formed at 2,300C as the moon’s outer layer melted in a blazing impact event.

Scientists now believe that impacts could have been key to the formation of the moon’s surface billions of years ago.

Previously scientists believed that the lunar surface was actually formed by magma rising from within the moon, and that asteroids and comets merely dented the surface.

Read more: Life on the moon? It could have happened billions of years ago

Dr James Darling, of the University of Portsmouth, said: "The discovery reveals that unimaginably violent impact events helped to build the lunar crust, not only destroy it.

"Going forward, it is exciting that we now have laboratory tools to help us fully understand their effects on the terrestrial planets."

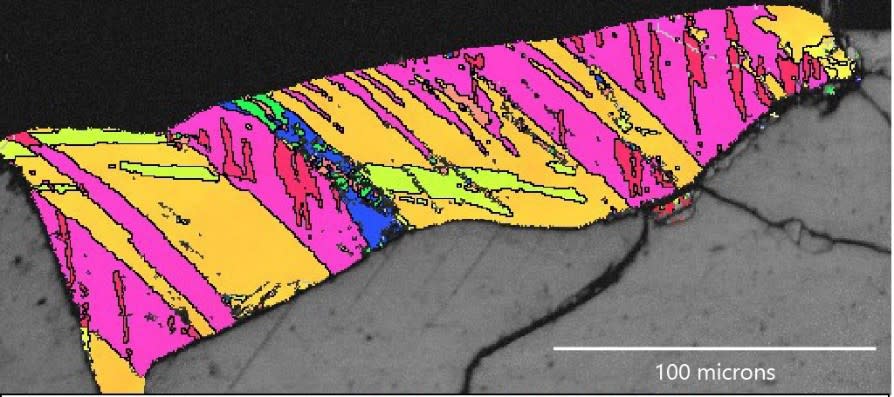

The team used a technique called electron backscatter diffraction to discover the former presence of cubic zirconia, a mineral phase that would only occur in rocks heated to above 2300C.

While looking at the structure of the crystal, the researchers also measured the age of the grain, which reveals the baddeleyite formed over 4.3 billion years ago.

Read more: Europe to start mining the surface of the moon

The high-temperature cubic zirconia phase must have formed before this time, suggesting that large impacts were critically important to forming new rocks on the early moon.

Fifty years ago, when the first samples were brought back from the surface of the moon, lunar scientists raised questions about how lunar crustal rocks formed.

Even today, a key question remains unanswered: how did the outer and inner layers of the moon mix after it formed?

This latest research suggests that large impacts over 4 billion years ago could have driven this mixing, producing the complex range of rocks seen on the surface of the moon today.

"Rocks on Earth are constantly being recycled, but the moon doesn't exhibit plate tectonics or volcanism, allowing older rocks to be preserved," explains Dr Lee White, Hatch postdoctoral fellow at the Royal Ontario Museum.

"By studying the moon, we can better understand the earliest history of our planet. If large, super-heated impacts were creating rocks on the moon, the same process was probably happening here on Earth."

Researchers from the universities of Portsmouth, Manchester and The Open University, were funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council for the study.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News