How Mohammad Rasoulof Escaped Iran and Why He Will Continue Fighting: “I Will Never Forget That the Islamic Republic Is a Terrorist”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Mohammad Rasoulof has arrived. The dissident Iranian director is at the Cannes Film Festival to present his new film, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, in competition, just weeks after he dramatically escaped Iran on foot, fleeing an eight-year prison sentence.

Details of the director’s harrowing escape were made public last week after he was safely away, ensconced in an undisclosed location in Germany. He made the decision to leave, to abandon his homeland and walk across the mountainous borderland after the authorities sentenced him to a lengthy prison term.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

His sentence also included a fine, the confiscation of property, and a flogging as punishment for bottles of wine the police discovered during a raid on his apartment.

Rasoulof had been arrested and imprisoned in Tehran’s notorious Evin jail in July 2022 for signing a petition calling on security forces to “Lay Down Your Arms” and exercise restraint in response to street protests. He was released temporarily on health grounds in February of last year and had been under house arrest ever since. But the threat of the original sentence still hung over him.

“I knew this sentence was going to be made public sooner or later because the case had been open for a while,” says Rasoulof, speaking to The Hollywood Reporter in Cannes. “So I was always asking myself: ‘How will I react when I finally find out that I’m sentenced to prison?'”

It wasn’t jail that frightened him. Rasoulof had done time before. But the thought that prison would prevent him from finishing his new movie — The Seed of the Sacred Fig was still in postproduction — was too much to bear.

“It was quite clear for me that what mattered most now was to go on making films and telling my stories,” he says, “I had more stories to tell, and nothing could stop me from telling them.”

Rasoulof chose Germany for his exile because he had lived in the country before —the German authorities had his papers on file and were able to ID him even without a passport, which the Iranian police had seized — and because The Seed of the Sacred Fig, a German co-production, was being edited in Berlin.

Regarding his escape, Rasoulof says that in Evin Prison he had heard about a secret route over the mountains to freedom and contacted his old cellmates.

“In retrospect, I think that I was extremely lucky and privileged to go to prison because that’s where I met people, very useful people, who helped me to cross the border,” says Rasoulof, smiling. “I wouldn’t have been able to do it otherwise.”

The Seed of the Sacred Fig was shot in secret and without permits. Rasoulof has been banned from making movies in Iran since 2017, when his feature A Man of Integrity screened in Cannes and upset the Tehran regime. (The film looks at endemic corruption in provincial Iran and the struggles of a good man caught between doing the right thing or joining the ranks of the corrupt elite.) His last film, There Is No Evil, which examines how ordinary citizens can resist Iran’s authoritarian regime, was made with funding help from Germany and the Czech Republic and screened in Berlin, in 2020, winning the Golden Bear for best film.

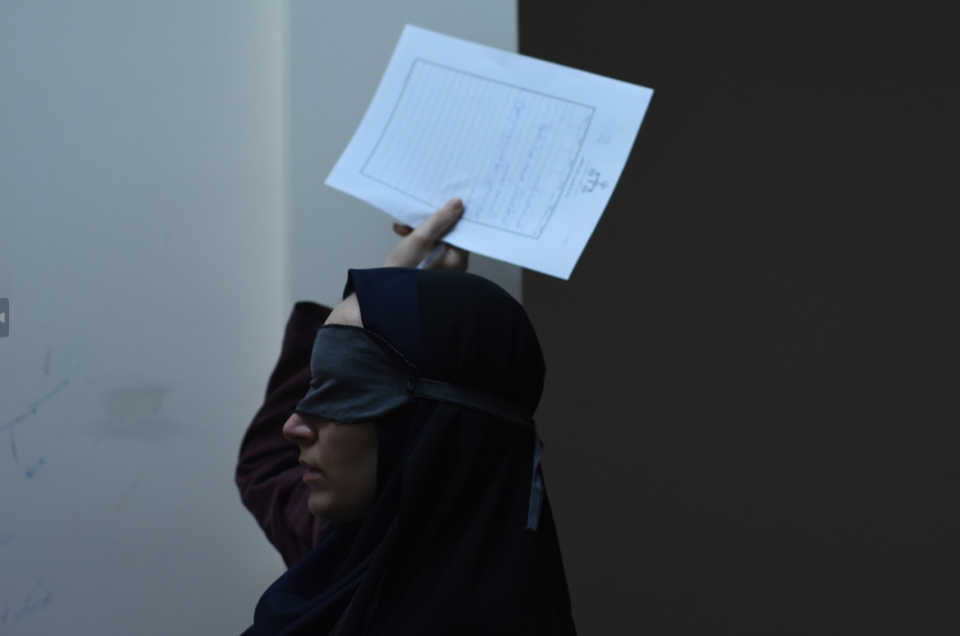

Both A Man of Integrity and There Is No Evil show the insidious impact of the Islamic Republic on the personal lives of ordinary Iranians. The Seed of the Sacred Fig goes deeper, following a single family enmeshed in the regime. Misagh Zare plays Iman, an investigator for Iran’s Revolutionary Court who is fiercely loyal to the government but has begun to question the arbitrary and summary nature of the death warrants he is asked to sign. At home, his wife Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) and daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki) become caught up in the Women, Life, Freedom protests sparked by the death, in custody, of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in 2022. Amini had been detained for allegedly not wearing her hijab properly and was reportedly beaten by the police.

Rasoulof says he decided to shift his focus from the victims of the regime to those enforcing repression after an incident in Evin Prison.

“There was a political prisoner on a hunger strike in my cell,” he recalls. “Things looked really bad at one point and the authorities were concerned. Some important figures of the administration came to meet him. While they were there, one of them took me aside. He took a pen out of his pocket and gave it to me, saying ‘This is my gift to you.’ I was very surprised, and he said: ‘Don’t think that we are happy doing this. Every day, when I enter this prison, I look at the gate and think: When am I going to hang myself in front of that door? Every day, my children ask me: What is your job? What do you actually do?’ That was the seed of this story.”

The Seed of the Sacred Fig, which Neon picked up for release in the U.S. ahead of its Cannes premiere on Friday, traces Iman’s struggles as he tries to square his conscience, and his love for his family, with his loyalty to the Tehran regime. Slowly, the fear and paranoia, the injustice and violence at the core of the authoritarian system, bleed into his private life.

“I used to observe the Iranian regime as a whole as a system and not really pay attention to its function,” says Rasoulof. “But with my last two films, A Man of Integrity and There Is No Evil, and here more, I’m getting closer and closer to the elements that make this machine work. Who are these people who help the regime? What are their motivations? I’ve tried to really get close to them to understand the psychology, their relation to this system they nourish.”

The Seed of the Sacred Tree violates pretty much every rule of Iranian state censorship. It shows its lead actresses without the hijab — the three young actresses in the film have now left Iran to avoid harassment or persecution — and it is directly critical of the regime. Rasoulof includes extensive cellphone footage posted on Iranian social media of police cracking down on Women, Life, Freedom protestors: beating young girls and women, dragging them across the street by their hair, tossing them into vans and driving off. It is unlikely the director will be able to return home soon.

“It is difficult for me to think about going back to Iran,” says Rasoulof. “I’m still in shock of having left the country. But now that I’m here, in Cannes, exactly the same place where I was seven years ago, I realize how much things have changed. And I see being Iranian doesn’t necessarily mean being in Iran geographically. Millions of Iranians have had to flee the country because they weren’t able to carry on with their lives as they wished. Now there is a culture of Iran that is all over the place in the world. And I’m one of them. This is a new way of living, a new way of creating. It will mean new restrictions. But I’m used to creating in spite of constraints and restrictions. I will keep telling my stories. If I have to do it using puppets or clay figures, I will not stop.”

Even in Europe, Rasoulof knows he can’t feel fully safe.

“Of course [the regime] can reach me if they want,” he notes. “I try not to think about it, while at the same time. I will never forget that the Islamic Republic is a terrorist. And terror has different ways of being applied. They can suppress people physically, and they can destroy them through their media, through their lies, and their discourse. This is something that I have in me, always. I don’t forget who the adversary is.”

But despite it all, the director says he feels “extremely hopeful” for the future of Iran. The Women, Life, Freedom protestors were driven off the streets, but the movement “has just gone underground, what was started is still growing,” he says. “What matters is that individuals have seen they can resist, they can do things differently. And we have extraordinary people, extremely brave women in my country. I know that change will come from women in the world, and more specifically the women in Iran.”

Best of The Hollywood Reporter