The Midterm Elections Could Be Hacked and We Won't Know Until It's Too Late

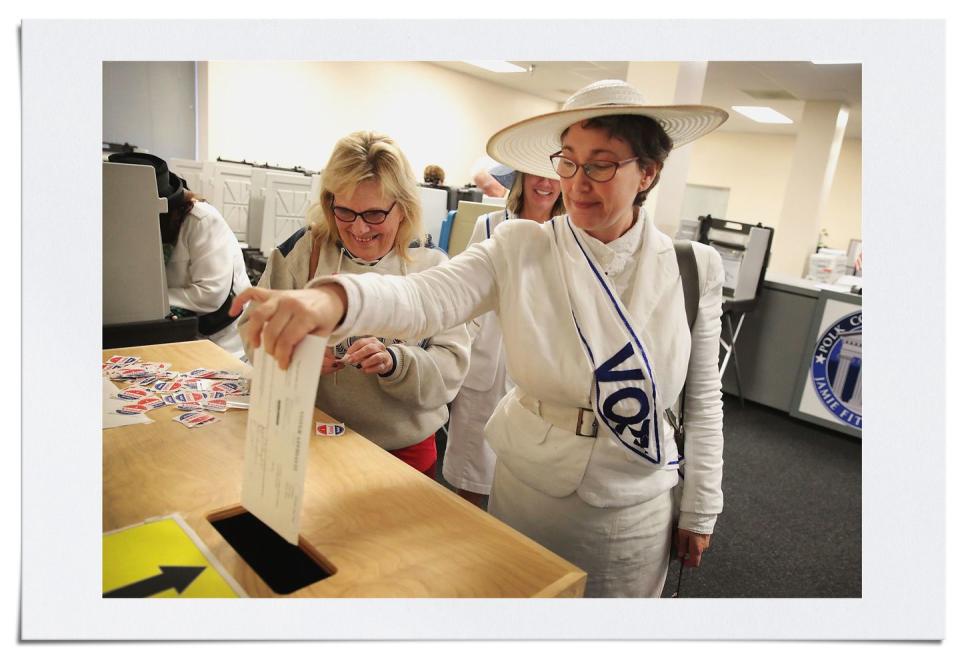

Millions of Ohioans will flock to the polls on Tuesday. They will wait in line, shuffle to the front, and give their name. Most of them will cast a ballot and carry on with their day. But thousands of others will be told they’re not on the list. They might think they’ve gone to the wrong polling place. If they haven’t voted in a while, they may assume they’ve been purged from the rolls. According to Ohio Voter Project, a nonprofit that collects and shares data about voting in the state, between five and ten thousand Ohioans are removed from the rolls every week.

Maybe they don’t know much about the laws around voting, and don’t know they can ask for a provisional ballot. And anyway, they have to return to work or pick up their kid from school. They’ve already been here a while, and they can’t afford to spend any more of their day at a polling station. Maybe they leave without casting a ballot.

Election security experts consider this one of many nightmare scenarios facing the American voting public-and thus, American democracy itself-on the eve of the 2018 midterm elections.

Ohio is a ground zero for their concerns because it has the most punitive voter-purge laws in the nation, which allow the state to remove registered voters from the rolls if they do not vote in three consecutive elections with a federal office on the ballot and fail to respond to a mailer. That's faster than anywhere else, and the Supreme Court's conservative wing upheld the "use it or lose it" measure, 5-4, in June. But that’s the mechanism to purge Ohioans legally. What concerns election-security types is the potential for something far more sinister. There's a chance, and not a particularly small one, that citizens could be struck from the voter rolls not by any legal or official mechanism, but by a hacker.

"I'm concerned that an effort to attack the voter registration system would go unnoticed," says Allison Berke, executive director of the Stanford [University] Cyber Initiative. "If some people showed up to a polling place, and they thought they were registered, and they're turned away, the assumption would be that they were unaware of these new requirements [like voter ID], or that they had been purged from the rolls through one of these other efforts to remove duplicate voters or voters who haven't voted in a long time. And so it wouldn't necessarily be immediately obvious that that was the result of a cyber attack."

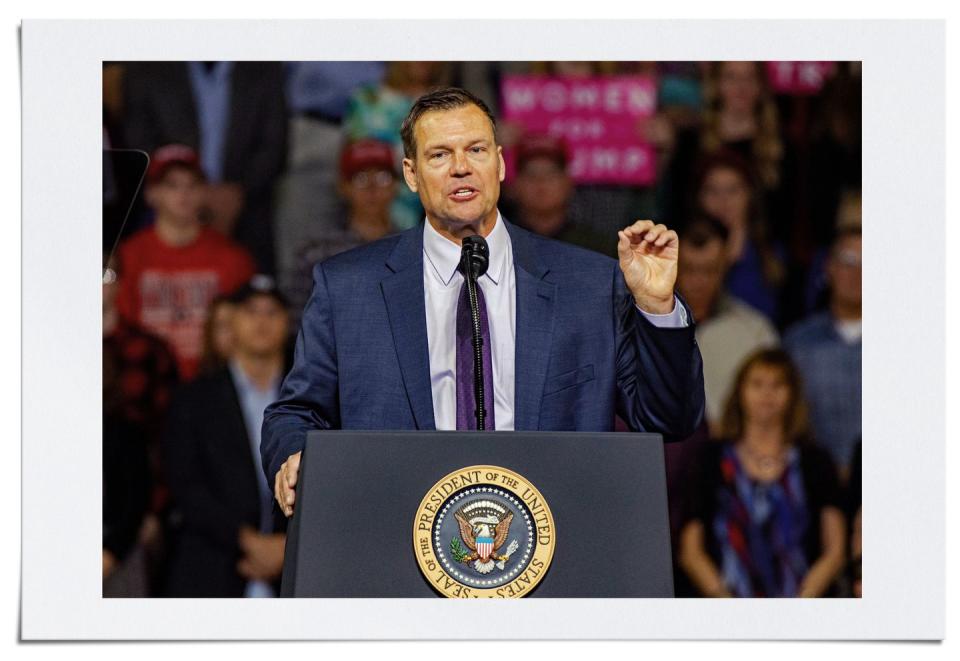

Ohio has opted into the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program, a scheme of laws and regulations developed by Kris Kobach-the Kansas secretary of state, now running for governor, who has distinguished himself as perhaps the country’s premier vote suppressor. Republican-controlled states across the country have adopted a swathe of policies to try to depress turnout, particularly among groups-people of color, younger people-who tend to vote for Democrats. All were enacted under the guise of combatting supposedly widespread voter fraud, of which there is no evidence. Among these are voter-ID laws, including “exact-match” policies like the one in Georgia; North Dakota’s residential-address statute, which targets Native American communities; and aggressive voter-purge programs like Ohio’s.

In a sick twist, these efforts may actually provide some of the very best cover for potential election hackers. Were you targeted by a Republican legislator, or, as the president has said, a “400-pound” guy sitting on a bed somewhere? The Ohio system also does not provide publicly available information on why a voter was removed from the rolls, according to the Ohio Voter Project, and removed voters are not informed of their change in status before Election Day. This lack of transparency only adds to the risk someone will be struck unjustly. When the right to the franchise is under assault by vandals both foreign and domestic, legislative and digital, it's hard to know just who ratfucked you.

And make no mistake: the digital vandals are coming. They might already be here. Russia's influence campaign in the 2016 election cost a few million bucks. That's some return on investment, and other actors-nation-states and otherwise-will have taken note. More than one analyst has stated publicly that hackers could have embedded themselves in our election systems months ago, forming sleeper cells in voting systems or voter registration databases. According to The Boston Globe, hackers have targeted "voter registration databases, election officials, and networks across the country" more than 160 times since August 1.

"In the 2016 election, adversaries only realized quite late in the year that maybe they should [interfere],” says Andrew Appel, a Princeton University professor who co-authored a report from the National Academy of Sciences focused on America's election-system vulnerabilities, released this September as a guide for policymakers.

“They didn't have a lot of time to prepare their attacks, and they only got a little bit into a few states' voter registration systems, for example, and not necessarily even into the systems that count up the votes. But now they've had a full two years."

At least one House races in Ohio is considered a toss-up, according to The New York Times: the 12th district contest between Troy Balderson and Danny O'Connor. The same two candidates faced off in a special election just last month that remained too close to call for three weeks afterwards. Eventually, Balderson was declared the winner-by a margin of barely more than 1,500 votes.

That is razor-thin, and the sad fact is that the results of an election do not even need to be changed, or that change does not need to be proven, in order for an election hack to prove effective. For some, including Russia in 2016, fomenting chaos and undermining the American public's faith in democracy would be a victory in itself.

The voter-registration systems are just one potential target, of course. The election hacking story that’s earned the most headlines is the possibility that the voting machines themselves could be hacked. Any actor with sufficient resources could probably pull it off, according to election security experts. They could program the machines to spit out a pre-ordained set of vote tallies, or to stop counting votes for a certain candidate at a certain threshold, or ensure the result falls outside the window that triggers an automatic recount.

And they’ll have plenty of opportunity to do it. Election administrators like to claim machines are not connected to the internet, but that’s not exactly true. They have to be programmed before the election with the candidates and layout of the ballot, which administrators often do by inserting a memory stick.

"The computers they use for programming these ballot definition files [on the memory cards] are typically just Windows laptops that are often connected to the internet,” Appel says.

Another vulnerability emerges when it's time for machines to "phone home" the results of an election. Some voting machines will send the final results over a cell phone modem, which administrators claim is fine because it's not the internet. But the phone system is connected to the internet. (Hello, dial-up sound.) And finally, there's the possibility that someone could go up to the physical voting machine, unscrew the back panel, and mess with it. Voting machines are delivered to polling places days before the election. They sit in that school or church or municipal building until they're picked up shortly after the election. If they're left unsecured at any point, they could be compromised.

All these scenarios can be remedied as long as voting machines include some kind of paper ballots-which is somehow still not universal, including in Georgia, but has been widely adopted as the standard-so local officials can conduct audits of results. In the scheme of election hacks, a direct assault on voting machines might be the easier variety to detect.

The far more diabolical, and less detectable, route could be to mess with the voter rolls-the list of names in a poll book that, depending on the state, may also include information such as your address. If you tamper with the rolls, people could be unjustly turned away when they show up to their local polling place. And it might not even be that a person is directly removed from the list.

“They could change the data in any way you could imagine,” Appel tells me. Hackers could change the polling place to which you’re assigned, according to Appel. They could alter your address so it doesn’t match the one listed on your ID-the same ID you might need to present to vote, if your state is run by Republicans who’ve taken an interest in voter suppression. For that matter, they could tweak your name in some way, such that it doesn’t match. They could change anything.

Any of these inconveniences might cause people to leave without voting at all. Or it might cause huge numbers of people to file provisional ballots, which take much longer to complete. Most polling places are equipped to deal with a dozen-or-two provisional-ballot requests at most. What if they get several hundred? Even if they can handle that, it will lead to longer lines. People may then leave without casting a ballot, or look at the line and keep on driving. All of that creates a perception of chaos, which undermines faith in the process and the results. To make things worse, the voter registration hack could go down as the election is happening. In some jurisdictions, election officials use an iPad or other electronic tablet to access the voter rolls. Those devices would be connected to the internet, which means they could be hacked. If there’s no physical voter roll as backup, there’s no way to know until it’s too late.

In fact, the biggest problem facing the voter registration systems is that they are connected to the web. Unlike with voting machines, this is absolutely necessary, because voters should be able to check their registration status online. They should even be able to register to vote online, although that isn’t available everywhere. But a jurisdiction that only uses electronic voter rolls, via tablet or other means-and doesn’t have paper records of those files-is playing with fire. And as it stands, the private companies that supply the voter registration databases are not always legally required to report when they are hacked. It mostly went unnoticed in the public consciousness, but these systems-like the one run by VR Systems, for example-were attacked in 2016.

There are ways to secure the voter-registration systems. First and foremost, states have to aggressively defend their systems on the cybersecurity front, and hold the private companies that create and maintain the systems accountable when they fall short. That should include compelling vendors to report hacking incidents by law.

The chances that states can keep up with the escalating capabilities of hackers-a constant demand in cyber warfare-are not high. So, as a contingency, experts recommend that administrators continually take snapshots of their voter rolls at various points, particularly as the election fast approaches and most voter-registration periods end. They should then use these lists, whose accuracy they can be sure of, on Election Day, and have paper copies available in case any electronic database goes haywire. None of these practices, however, are standard across the nation.

You can also play an active role yourself by checking your registration online, to be sure your status or polling place hasn’t changed. Then, above all, show up-and do whatever it takes to vote. If you’re told you can’t, demand a provisional ballot. A wide-scale election attack could lead to a high volume of provisional ballots, and it would then be ruthlessly litigated in the courts whether they should be included in the vote tallies. But that’s better than having no voice at all.

The state of Ohio announced a $12.2 million investment in election security initiatives in September. The money, acquired through the Help Americans Vote Act, or HAVA, which Congress introduced after the Florida recount debacle in 2000, will pay for an update of the state’s voter registration database, bolster cybersecurity for county boards of elections, and carry out audits after Election Day, according to a press release. The Ohio secretary of state’s office declined to comment beyond that release, but a report from the left-leaning Center for American Progress suggests the state’s audit requirements do not test election outcomes with a high degree of confidence, and that the state’s voter registration system is around 10 years old. That’s a lifetime in the cyber wars, and if it’s accurate, it’s a serious problem.

For its part, the Department of Homeland Security is attempting to help state and local election officials grapple with a series of unprecedented demands. American elections are now a battleground for international combat. The best argument for federal intervention in elections is that it’s a vital national security issue. Consequently, election infrastructure should fall under the purview of the federal government, which is bound by the Constitution to protect the homeland from foreign adversaries.

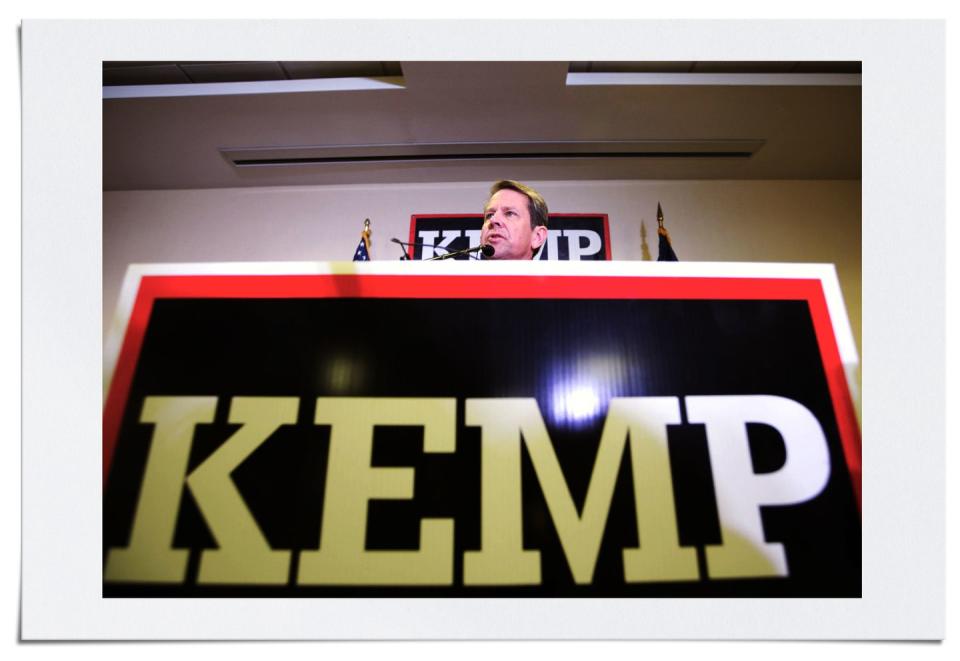

That’s what President Obama’s Homeland Security Secretary, Jeh Johnson, tried to do in the run-up to 2016-except he faced a volcanic response from Republican state officials, who called it an attempt at federal overreach. (Brian Kemp, now running for Georgia governor in a closely watched election, was one of 11 secretaries of state to reject federal cybersecurity assistance of any kind. In related news, Kemp’s office purged 1.5 million Georgia voters from the rolls between 2012 and 2016.) After the intelligence community’s January 2017 assessment determining that Russia had meddled in the election, however, the “critical infrastructure” designation was granted.

That was part of a larger softening from Republicans towards the federal government involving itself in election security. In Congress, they acquiesced to a funding boost to the tune of $380 million. States have gotten to work spending that, too, but it’s how it’s spent that matters. In Ohio, it’s not clear that the money will prevent someone, or some country, from tampering with voter rolls.

It’s also unclear whether the DHS, which declined to comment for this article, has the resources to put out all the fires that may flare up around Election Day. There are surely scores of people dedicated to protecting free and fair elections in America, but the agency at large has a host of other issues to which it must attend. Often, these problems are more politically volatile-or, in some cases, valuable-to the head of the Executive Branch. Certainly, what’s happening at the border, for instance, gets far more daily scrutiny from outside, including from the media, than does the security of our elections.

And that, in the end, is the dark undercurrent of all this. Even after an election in 2016 that was critically marred by foreign interference, the avalanche of shiny objects cascading daily into Our National Dialogue in the Trump Era has all but obscured the vital threats awaiting our election system. Some candidates could be buffeted by an influence campaign. Voting machines could be hacked. Or, perhaps most perniciously, people could be robbed of their registration-and thus, their voting rights-and never even know it.

The core of our democracy is at stake in this election, and not just because the Republican Party has embarked on a shameless campaign to limit the ability of Certain People to vote, and to dilute the power of those votes through structural tools like gerrymandering. There is a legitimacy crisis throughout the many institutions of our democratic republic, as Americans lose faith in Congress, the courts, the media-pretty much anything that isn’t the military. If they lose the faith that our elections are free and fair, you can’t help but despair for a nation already teetering on the brink. It could happen-and not with a bang, but a whimper.

('You Might Also Like',)