Michael Ian Black wrote a book for his son about how to be A Better Man. Has he read it yet?

Why is it boys that are pulling the triggers?

That question rang inside Michael Ian Black’s head in the aftermath of the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., that killed 17 innocent people. The author, comedian, and father of two lived near Sandy Hook, C.T., in 2012 when a similarly devastating shooting took place. Once again, the shooter was a troubled young man. By 2018, Black was set on finding a semblance of an answer by pouring his heart out in a letter to his son, Eljiah, who was leaving for college at the time.

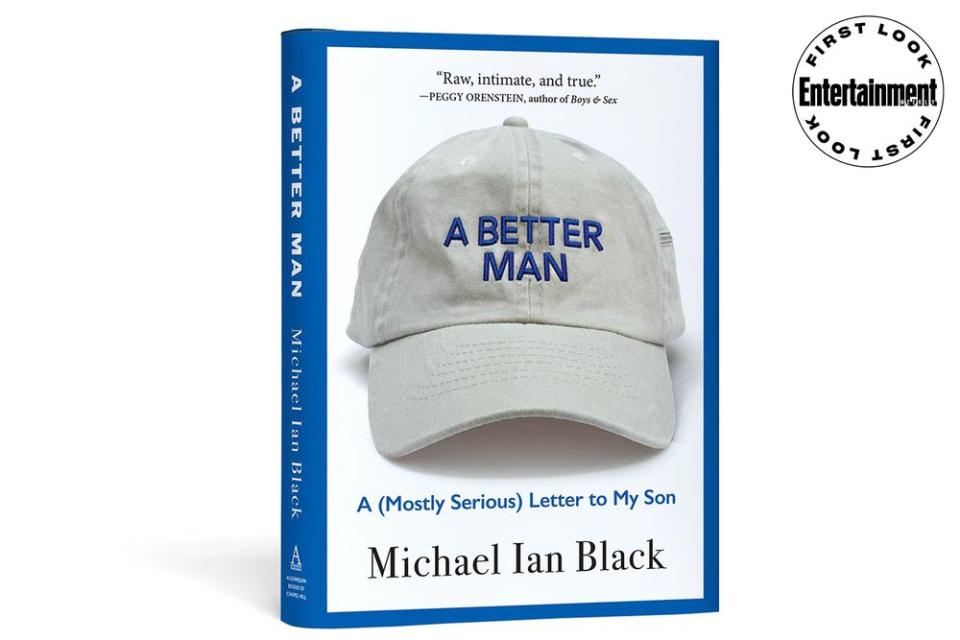

That letter eventually became the upcoming book A Better Man: A (Mostly Serious) Letter to My Son.

“I didn’t want to pretend to be an expert on something that I’m not an expert on,” Black tells EW. “I’m not an expert on gun violence. I’m not an expert in gender theory or gender studies. But what I am an expert on is being a father to my son. I’m an expert in understanding my own struggles with what it’s like to try to be a man. I’m an expert in those questions. I don’t know that I’m an expert in the answers.”

A Better Man doesn’t hit bookshelves until May, but EW can exclusively reveal the cover below. We also spoke to Black about why the cover features a subversive take on Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again hat, the state of being an older white man in comedy, and whether his son has read the book written for him.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: You wrote children’s books around the time you had young kids. Now you’ve written this candid book about showing your son the right path in what can be a very confusing world. How did you first decide to explore your writing career, since you started out as a comic?

MICHAEL IAN BLACK: Well, I’ve always written. I didn’t really realize that I had always been writing until actually fairly recently, when I found myself writing again. I wrote when I was a kid, I wrote stories. And when I was in college, I wrote sketches and TV shows. And then I started writing books. The only thing that changes from over the years is either the format, or sometimes the tone. Like, this new book is pretty serious, for the most part. I remain unconfident that anyone is going to want to read it.

It can be difficult to be that vulnerable. What was it for you that made you want to get into this more serious writing?

It was the Parkland shooting in Florida. It really got me thinking more deeply about boys. Being a boy. Being a man. Having a son. It’s always been in my comedy. Questions about what it means to be a guy. There was always jokes about stuff like that. But I never really spent any serious time ruminating about my own feelings on the subject and what I wanted to impart on my kid as he left home. It was the Parkland shootings that sparked that. Before that was Sandy Hook. And we live right next door to Sandy Hook. That happened when they were littler. My two kids [Elijah and Ruthie]. That got me interested in just the phenomenon of gun violence. It was gun violence that led me to ask the question, “Why is it boys who are pulling the triggers?” That was the question started the book.

You have a quote in the beginning of the book from the Village People song “Macho Man,” and masculinity is something you definitely dissect. Was there any specific reason you decided to start your book with the Village People?

There’s a couple reasons. The first is because the book is literally about “What does it mean to be a macho man? What is that? What does that mean? How do we evaluate what that is? How do we evaluate what masculinity is?” Then there’s obviously the irony of the fact that it was the Village People asking that question, a group that was embracing both every hyper-masculine stereotype while being gay icons. I’m not saying those two things are in opposition. You can be obviously a very masculine gay guy. But at the time, especially when that song came out, there was total ignorance of who they were and what they were saying in a straight world. In the same way that people don’t understand the masquerade, the almost drag-show element, of being just a being a regular dude. All gender itself is so performative. We put on essentially costumes and signifiers that say, “This is the kind of man I am. This is the kind of woman I am.”

What was your involvement in the cover art, and how did you decide to have a hat with the A Better Man title on it?

The concept was presented to me and I really loved it right from the beginning, because I thought it was really clever and a little bit subversive. Clever because that ball cap is so ubiquitous in the culture, and the kind of dude culture. Then [the cap] was co-opted in the 2016 presidential campaign, which came to represent something much more, I would say, corrosive. It went from being something that Hootie and the Blowfish fans wore to representing the worst of our national character.

In the book, you touch on the idea of white men feeling like they’re losing their sense of control over the culture. Is this letter to your son something you’re putting out there not only for him, but for those white men who may be feeling like they’re lost?

Yes, i’m trying to make the argument that men’s place in the culture is changing. And rather than shrink from that, there’s a real opportunity for guys to embrace it, and to let it work to our advantage. If you’re looking at it from a very narrow point of view, which is the point of view of the status quo — an example of the status quo would be, let’s say, a 48-year-old heterosexual white dude, and I’m just describing myself. If you’re just looking at it through that narrow point of view, you can look back at the last 60 years and say, “Oh gee, African-Americans have made tremendous progress. Women have made tremendous progress. The LGBT community has made tremendous progress. And all of it feels like it’s coming at my expense.” That interpretation, I don’t think is a correct interpretation, but it is one interpretation. And it’s a prevalent interpretation. I would argue, and this book is trying to argue, that all of those movements, and in particular the feminism movement, create opportunities for 48-year-old straight white dudes. The work that women have done to move forward in the culture is work that we can piggyback onto. We don’t have to fear those changes, we can welcome them and learn from them. And then help propel them.

Let’s talk about comedy for a second, because this idea plays a part in your book. There’s a segment of comedians, who tend to be older and white, that are against what has been called PC culture, where you can’t say this and you can’t say that. Is it because, like you write in your book, there are men trying to grasp the last ounce of control that they thought they had?

Well, maybe that might be part of it. What’s different now, and the reason that that debate is happening in the comedy community, as it’s happening in the larger culture, is that they’re undergoing some of the same changes. There are now opportunities for people in the comedy community that didn’t exist even five years ago. You’re seeing an explosion of women and people of color and gay people and trans people and disabled people. Whoever the gatekeepers were in comedy, you’re seeing those gates come crashing down. It’s no surprise that all the white dudes who have essentially owned comedy since its inception are going to feel threatened by that. And the answer is: Everybody’s game has to get better now. Because there is so much more talent out there that just hadn’t been visible until now, for the first time in American entertainment history. It’s a good thing that we have this problem. I’m thrilled that we have this problem. I’m less thrilled about my own professional prospects as a result of this problem. Because again, like, I’m the dude that benefited from it. I’m one of those dudes that has spent 30 years benefiting from an entrenched system that rewarded dudes like me. Now I have to up my game.

Have you shown your son A Better Man? If so, what was that like?

I gave him the book. He knew I was writing the book honestly. I said, “I wrote a book for you.” I gave him the PDF of it because that was all that existed right before he left for this freshman year of college. To my knowledge, he has not read a single word of it.

How long was that ago?

That was in late August. What I suspect is happening is he’s saving it up for when I die. And then he feels so guilty that he never read it that he’ll finally crack it open. And after 10 pages say, “Yeah, this doesn’t work,” and put it away.

Is it because he feels like he’s read these pages before? He’s gone through the experiences, he doesn’t need a rehash them.

I suspect that has a lot to do with it. I also think it has to do with, it’s hard for a kid to read about their parent’s vulnerabilities. Even when the kid is an adult or becoming an adult, I think it’s hard to read about your dad’s fears and insecurities, and at times deep sadnesses.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Related content: