From Merriweather Post to Trump: New book by UCF professor details history of Mar-a-Lago

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Mar-a-Lago’s story is much more than that of a grand Palm Beach mansion built by Marjorie Merriweather Post, one of the wealthiest socialites and businesswomen in American history, with her second husband, E.F. Hutton.

It’s more than a palace and private club owned by former President Donald Trump, now notorious as the site where FBI agents scoured its interior for classified government documents.

Mar-a-Lago is a survivor. The property at 1100 S. Ocean Blvd. has withstood hurricanes, threats to subdivide it, the high-stakes divorces of its owners, heirs who didn’t want it, a town that opposed opening it to the public, a rejection by the state of Florida, an abandonment by the National Park Service and financial collapses. It has been visited by U.S. presidents through the years, and a couple of them took actions determining its future.

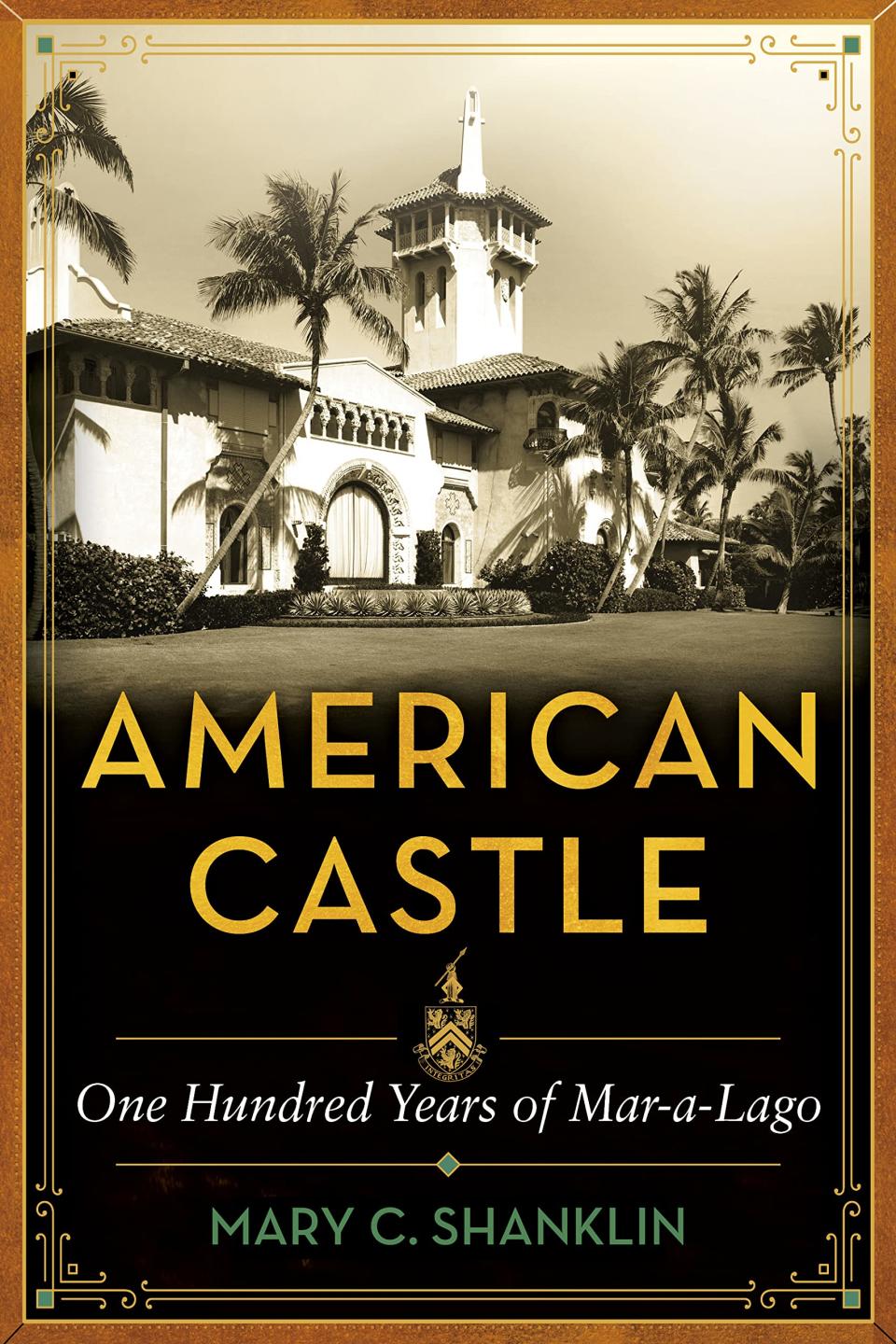

“American Castle: One Hundred Years of Mar-a-Lago,” by University of Central Florida professor and journalist Mary Shanklin, is a fast-paced narrative that takes a detailed look into the 118-room, 17-acre estate’s history. Published by New York-based Diversion Books, the 304-page hardcover book is being released Tuesday (price: $29.99).

“Everybody has heard of Mar-a-Lago by now,” said Shanklin, who lives in Winter Garden, and toured Mar-a-Lago in 2018. “What people do not understand is that by virtue of the government they actually owned Mar-a-Lago at one time. It was government property.”

Shanklin spent four years researching the book, and her extensive bibliography lists close to 200 sources, from the presidential libraries to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Marjorie Merriweather Post’s archives, the Congressional Record and newspapers.com. The Historical Society of Palm Beach County also was extremely helpful, she said. Many were previously untapped interviews, documents and recordings.

Starting in the 1950s, many of the monumental Palm Beach residences built with pre-Depression wealth were being “crushed out of existence by New Yorkers who pined for new seaside villas,” Shanklin writes, but Mar-a-Lago escaped that fate.

“Grab, chop up and build anew was the mantra for prized pieces of property across the country and particularly on a tropical peninsula that drew monied Northerners like human flesh draws mosquitoes,” Shanklin writes.

The book is about Mar-a-Lago, but also includes extensive treatment or mentions of many other subjects, such as the 1920s Florida land boom; Post’s other residences, Hillwood and Camp Topridge; The Breakers fire; Post’s four husbands; and other famous estates such as the Stotesburys' El Mirasol. It provides details about how the super-rich lived then, and after Trump acquired the estate in 1985. Trump’s renovations increased the number of rooms to 126 and added a spa.

Post, who inherited the Postum Cereal Co. that would later become General Foods, died at age 86 on Sept. 12, 1973. She bequeathed the property to the National Park Service, but Mar-a-Lago was returned to the Post Foundation in 1980.

“What has happened at that place over the last half-dozen years, nobody could have guessed,” Shanklin said.

Mar-a-Lago’s saga began in 1922 when Post began a search for land to build her winter trophy estate and found it in 17 acres of jungle on a coral reef between the Atlantic Ocean and Lake Worth with 500 feet of oceanfront.

Shanklin quotes Post: “It had to be unoccupied land from the ocean to the lake and well-wooded,” she said almost four decades later, describing the bug-infested jungles. "We became quite used to following the animal paths, sometimes on our hands and knees.”

In the book, Shanklin writes: ”Decades later, Interior Secretary [Stewart] Udall could have told her that the location would be revered by her guests, coveted by developers and controlled by neighboring islanders. The very attributes that would make it a celebrated stop for royalty, power brokers and socialites would ultimately make it impossible to save for the enrichment of society, as Post had worked for during much of her adult life.”

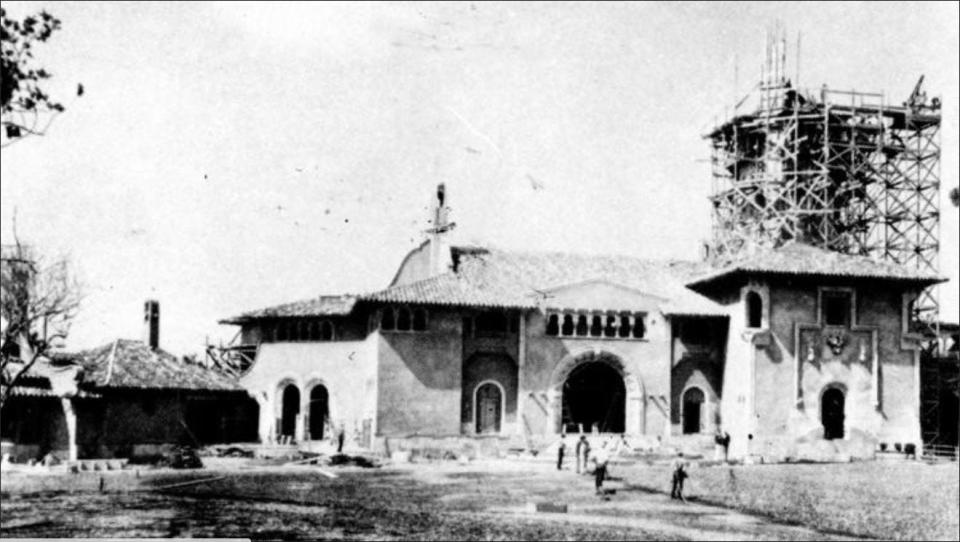

From 1923 to 1927, about 600 workers constructed Mar-a-Lago, designed with eclectic Spanish, Venetian and Portuguese styles. Artisans installed 36,000 Spanish tiles in the entrance hall, patio and cloisters. Tons of Doria stone from Italy were carved into wall facings, archways and sculptures.

Building Mar-a-Lago: Marjorie Merriweather Post’s Palm Beach showplace

As Mar-a-Lago was being built, the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 damaged towns to the south, raising awareness of what storms could do. The even more devastating 1928 hurricane did major damage in Palm Beach County, drowning thousands of people, mostly around Lake Okeechobee. Mar-a-Lago survived mostly intact. The storm downed a few dozen palms and shattered a large, Roman-style window.

Post was, of course, protective of the mansion, and handed out shoe covers to women who arrived with stiletto heels. Then there were the un-Palm Beachy square dances she held that ended promptly at 9 p.m., but were quite popular.

Memory Lane: Marjorie Merriweather Post loved to dance

For a number of years, Mar-a-Lago “went dark,” Shanklin said. Instead of coming to Mar-a-Lago for the season starting in 1932, the Huttons sailed the world.

“When she and E.F. Hutton had that extraordinary yacht, all of a sudden, they did not have to go back to the same place,” Shanklin said. “It was a hit on the Palm Beach economy, not just on the workers staffing Ma-a-Lago. It was the social hub.”

When Post married Joseph Davies, a diplomat more at home in Washington, D.C., than in Palm Beach, it was almost five years into their marriage before they opened their winter home.

As Post fought to preserve Mar-a-Lago by urging the federal government to buy it, in 1968 she invited Lady Bird Johnson, then the first lady, for a visit. Johnson, who called Post “the last of the queens in a setting that probably will not continue or be duplicated in this country in the lifetime of my children,” was convinced it should be preserved and become federal property.

Shanklin uncovered a little-known provision tied to the property by the National Trust for Historic Preservation that requires allowing a small select group of people to visit Mar-a-Lago one day a year, opening it to scholars, children and others who would not normally go there.

Trust officials told her that with so many events and fundraisers at the estate, they felt the obligation was fulfilled.

When Trump first became president, Shanklin started “poking around” into its history. She found a National Park Service public forum where someone referred to an out-of-print book by a former National Park Service administrator, Dwight Rettie, called “Our National Park System: Caring for America’s Greatest Natural and Historic Treasures.”

“He laid out a well-documented fascinating case about how Mar-a-Lago became part of the National Park Service and suffered the rare humiliation of being divested from the Park Service. Before it was the Trump White House, there was President Nixon signing the act for it,” Shanklin said. “It was (President) Jimmy Carter who signed the approval to have it divested.”

While people thought the rejection was because of the expense in maintaining Mar-a-Lago, the truth was the town did not want it open to the public. Robert Grace, then a Town Council member, led the fight against the proposal and would also later file a lawsuit against the property becoming a club.

Preserving Mar-a-Lago: A look at historical features Trump can’t touch

One of Shanklin’s favorite parts of the story is when Florida Congressman Dan Mica, who was trying to figure out how to get Mar-a-Lago out of the National Park Service, was confronted by California Congressman Phil Burton. Burton, who was considered bombastic and crude, wanted Mar-a-Lago to remain part of the Park Service.

When Burton found out there was a rider attached to a land partition act that booted Mar-a-Lago from the Park Service, Burton confronted Mica. He grabbed him by the lapels, picked him up and said, “I will get you, Mica, I will get you.”

The concern about visitors coming to and from Mar-a-Lago is ironic, considering the crowds that have gathered in the Trump era.

Trump was able to preserve the property by turning it into a club, which was the idea of his attorney, Paul Rampell. The money from the club memberships and special events has made it possible for Mar-a-Lago to be kept in impeccable shape, Shanklin said.

What lies ahead for Mar-a-Lago isn’t known.

Oops! Eric Trump denies Mar-a-Lago sold for $422 million; Zillow admits listing error

“We really have to appreciate that it is still there, and that it is still in its original setting,” Shanklin said. “I do feel like even though the Trump era has meant the streets are filled with MAGA people and balloons, all this stuff has added a certain cachet and helped make it more marketable and attractive.

“The last half-dozen years have shown us, if nothing else, that you can’t predict anything. That place could still end up in public hands and be done in a respectful way,” Shanklin said.

Mar-a-Lago’s story is filled with ironies, Shanklin said, and she feels that history repeats itself.

“We don’t know where this is headed. The only thing we know is that change always happens,” she said.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Daily News: A Palm Beach survivor: New book explores Mar-a-Lago's rich history