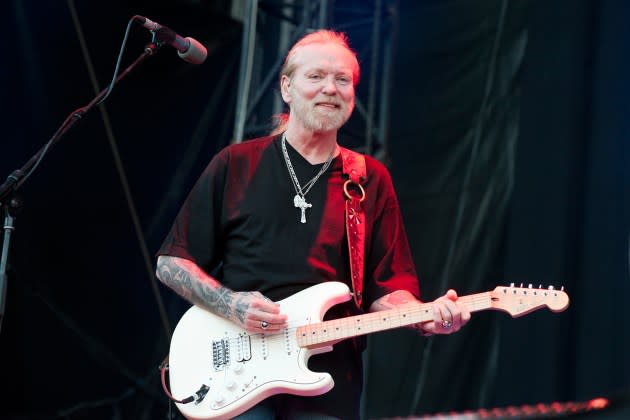

In Memory of Gregory Allman: Writer Alan Light Recalls His Time With the Midnight Rider

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Gregg Allman’s devoted manager, Michael Lehman, first spoke to me about working with Gregg on his autobiography, I was skeptical. I had written a few stories about Gregg before, and knew that he was a reluctant interview — he could be serious and thoughtful, but was far from a life-of-the-party raconteur. We discussed at length whether Gregg was really prepared to commit to the requirements of this process, and open up sufficiently to give such a book what it would need to succeed.

Once we decided to move forward, we were already on an accelerated schedule. Our first session was set for sometime in the spring of 2011, less than a year after Gregg’s liver transplant. And then, before we met up, he suffered another medical emergency — this time going Code Blue in the hospital after blood had seeped into his lungs. Still, Michael assured me that Gregg wanted to proceed with the book.

More from Billboard

Geffen Records & David Dollimore Launch New Electronic Label, Disorder

New Ticketing Bill Requiring All-In Pricing, Refunds for Canceled Shows Takes Key Step Forward

We first sat down in northern Florida, where Gregg had gone to rest and recover. He needed a walker to move around, and he looked old and very fragile. As soon as I turned the recorder on, he told me about a vision he had while he was unconscious in the hospital — a dream in which he came to a bridge and someone with long hair (his late brother Duane, he assumed) stood on the other side, but he decided that it wasn’t time to go across. It was eerie, and ended up being the prologue to the book that was eventually titled My Cross to Bear. But I was still convinced that this project would never actually happen.

But soon enough, Gregory — his preference as a moniker; he said that he felt like “Gregg Allman” was just a brand name — returned to his home outside Savannah, Georgia. Every few weeks I would fly down, check into a Motel 6 next to a Waffle House off the highway, head down the road to his house and spend a couple of days talking through his astonishing history. He got a little stronger each time — though he couldn’t talk for a minute longer than two hours. I didn’t even need to check the timer on the recorder to know when he would start to tire and drift off.

Whatever his physical limitations, though, and whatever his usual attitude was toward interviews, Gregg was fully committed to the book. Maybe his medical problems had given him the incentive to get his story down one time, in full, but it was clear that nothing was off the table, that he was ready to talk about anything and everything he had been through.

We would sit on the couch, and he was often proudly wearing the purple psychedelic booties that his mother, already in her 90s, had knitted for him. His beloved “house manager,” Judy, kept the coffee on and meticulously laid out the dozens of pills he needed to take to keep up his immune system.

His dogs always cheered him up. No matter what he was recounting — his father’s murder when Gregg was just 2 years old, the years of substance abuse, the bandmates he had lost along the way — he would perk up when his two little puffball pups would skitter into the room. And while he expressed regret for the pain he had caused others in his life, for the chaos of his six marriages — with deadline approaching, we realized that we hadn’t even mentioned one of the wives in the book, and he struggled to come up with any memories of her at all — and his messy relationships with his children, he never made excuses.

It was stunning how present Duane seemed to be in Gregg’s mind. He would bring him up constantly — he had notes from Duane framed on the walls of the house, and always emphasized that The Allman Brothers Band was Duane’s vision and would always be Duane’s group. Maybe it’s not surprising that, 40 years after his death, his brother was still so important to Gregg; think about what it must feel like to go out night after night fronting The Allman Brothers Band as the only living Allman Brother. Gregg clearly felt some kind of survivor’s guilt, but Duane’s memory also seemed to give him a drive and a purpose for his musical gift.

Make no mistake: Gregg was proud of his band, and despite his laid-back persona, he was competitive when it came to making music. He understood the Allmans’ legacy in helping to create both the southern rock and the jam band movements, but he also knew that his group could play circles around most everyone often classified as their peers. He bristled at any comparisons to Lynyrd Skynyrd or the Grateful Dead — as far as he was concerned, The Allman Brothers were in another league.

A big part of that distinction was, of course, his magnificent voice. Gregg belonged to the blues tradition first, and he loved talking about B.B. King or Little Milton, and always traveled with an iPod filled with a custom-programmed, all-blues playlist. He spoke of Otis Redding with an almost religious fervor, recounting how the night he and Duane saw Otis sing was the moment that changed their lives, and convinced them to be musicians.

Drawing on that kind of soul, and the authentic blues feel that came directly from a lifetime of hardship, separated the Brothers from the pack at least as much as their brilliant musicianship. His songwriting, especially early in his career, pulled from that same hard-fought place, expressing emotions and ideas that seemed impossible for someone of such a young age.

We didn’t become real friends from working on the book. We were both there to do a job, and he wasn’t the sort to want to hang out. We did a few public events together after it was published in 2012, and then I would see him for a minute before shows in New York City. Then, after a while, I would just go to watch and marvel at the power of the music.

Gregg had a hard time slowing down. He would take me out to his garage and show off his motorcycles, dreaming of being able to get back in the saddle and open them up on the highway. But as I drove away from the house, I would see him and Judy in my rear-view mirror, climbing on to bicycles for a careful lap around the block, helping him build back his strength.

Material for a book gets stitched together out of order sometimes, so I don’t know when Gregg said the words that come near the end of My Cross to Bear. But I sure do remember him saying them: “When it’s all said and done, I’ll go to my grave and my brother will greet me, saying, ‘Nice work, little brother — you did all right.’“

He damn sure did. He walked through so many fires that we all started to suspect that he was unstoppable. Now that time has inevitably caught the Midnight Rider, I’m honored and grateful that I got to be along for part of the ride.

Best of Billboard