Meet the remarkable subject of Dave Eggers' new book The Monk of Mokha

Dave Eggers is telling the remarkable true story of a Yemeni coffee farmer for his next book.

The Pulitzer Prize finalist’s upcoming The Monk of Mokha marks his first nonfiction work in nearly a decade. He traveled the world for research in his portrait of Mokhtar Alkhanshali, a Yemeni-American who grew up in San Francisco, moved to Yemen at 24 and immersed himself in its coffee farming culture, and survived a deadly civil war which continues on to this day. What results in The Monk of Mokha is a vibrant depiction of courage and passion, interwoven with a detailed history of Yemeni coffee and a timely exploration of Muslim American identity.

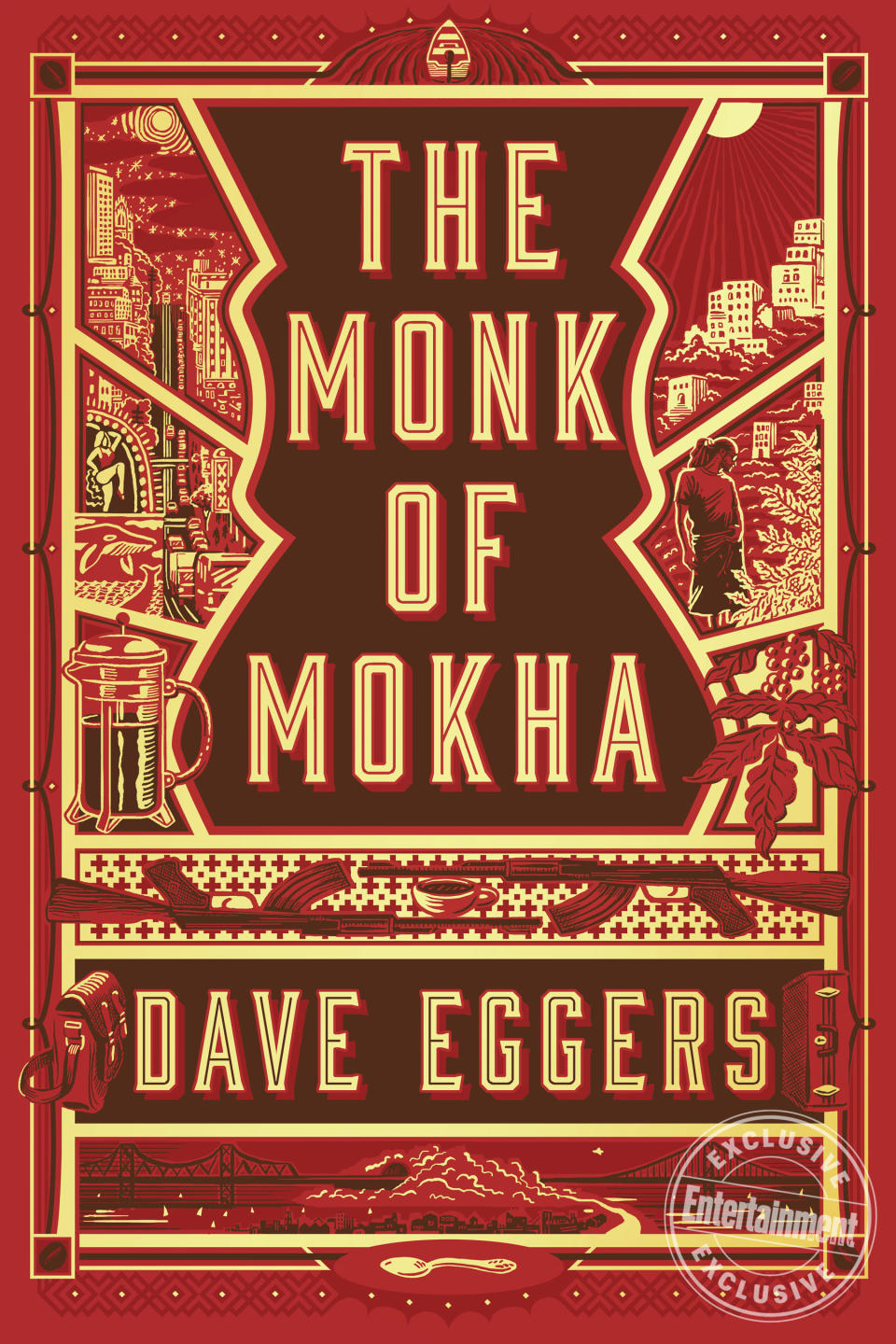

Alkhanshali, now back in San Francisco, spoke to EW from his hometown in a frank interview, in which he revealed how he worked on the book with Eggers for years, reflected on his harrowing but transformative experience living in Yemen, and explained why he thinks The Monk of Mokha is a vital story to tell in the Trump era. Read on below, where you can also check out an exclusive look at the book’s cover. (Pre-order here.)

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: Can you talk a little bit about how you decided to get together with Dave Eggers for this project?

MOKHTAR ALKHANSHALI: I don’t know if I would use the word “decided.” I met Dave maybe seven years ago, six years ago. It’s funny because I didn’t know he was this famous author. A friend of mine was working on a script for a TV series about an Arab cop, and the main character was Yemeni. So they wanted somebody to give an accurate portrayal of the Yemeni community and make sure it was accurate. They asked me to read the script; I read it. If you ever meet Dave, he’s so, so humble and the quintessential writer. He has an old cellphone, he doesn’t like social media. I came back from Yemen, and I had just escaped my life. I met up with him and I was going through a little bit of my journey. I was still trying to process a lot about what had happened to me, and he made his notes. The next day he called me, and he’s like, “Listen, your story’s incredible and it’s really inspirational, and I would be honored to write a book about your life.”

I didn’t understand. I was like, “What are you going to write about?” I initially told him no. I remember like a week later, I told a friend of mine about this. And didn’t even say the name correctly: I said “David Edgers.” He’s like, “Who?” And I said, “You know, this author,” and my friend was like, “He’s one of the most incredible authors alive. This is an amazing opportunity to tell the story of coffee, your work.”

So you weren’t familiar with his work?

No, I wasn’t. When you have accessibility to somebody — I had him in my phone for years, four or five years before that — you just don’t assume this person’s famous. And also, he’s extremely humble in person. He’ll leave to go to a meeting, and you’ll only find out later he was meeting John Kerry or Emma Watson or something.

Did you have any concerns, regardless of whether you knew who Dave was as an author, about making your story public and how it would be told?

When I had worked with him previously, I got to know him as a friend. That’s how I first knew Dave: I knew him as a friend. He’s led a really remarkable life and is a really, really great guy, so I wasn’t too hesitant about that. Even before he began writing … he spent a long time talking to me about this. In the process of three amazing years, he’s gone to Ethiopia, to Yemen, to the coffee farms — he’s really immersed himself in my life. Anyone who’s met him, my friends and family, will tell you what a good person he is. I was more concerned about my personal life — and I still am, you could say — and how people would [react].

What was your process with Dave like, working on and shaping this book?

I was living my life. I’d just come out of a war zone, I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to run my business and help my farmers — the ports are still closed, there are still airstrikes going on in Yemen even today. I’m just figuring out my life while he’s behind me, following in and being a part of it in that way. The first year was pretty intense because we would meet like five days a week and have these long interviews, and he would voice-record my interviews. Then he would take notes and would go into everything. After a while, this thing that happened to me, he would ask about it at different times, different months. He’d interview all the people involved, like my friends and family. There were news pieces about them, there were pictures, and I was pretty much like an open book for him — just kind of go into my life and piece it together.

The book is really about how you were drawn to Yemeni coffee, and that culture and industry. Why did it become so central to your life?

A lot of immigrants will tell you this: Your parents leave those countries for another opportunity, and nobody has the idea of going back. So my parents would tell me, “Mokhtar, if you don’t do good in school, we’re going to send you back to Yemen and work on a farm.” That was my family’s threat. I didn’t even think about going to Yemen. My background was like, I wanted to do something with social impact, and so I did a lot of work around civil rights issues, and I worked with groups like the ACLU here in San Francisco. And so I thought that the best way for me to do social impact was to be a lawyer. I thought that’d be great, my parents would always want to have a lawyer as a son. And all my work in school and my efforts were about becoming a lawyer.

And then one day I walked into a coffee shop … and I had a cup of coffee from Ethiopia. It blew me away how it tasted. I tasted blueberries, and was like, “This is not normal coffee.” I’m used to drinking diner coffee where you have to put sugar and cream to make it drinkable. Growing up in San Francisco, there’s a huge food culture — I was a foodie. So I learned about how they are different varieties, and seasonality. And I learned, more importantly, about direct trade — and how if you paid more to farmers, they could produce better-quality products, and you could pay for things better. I thought, “How cool would it be to start a business where it’s really a model of social impact?” My family’s from Yemen. I grew up hearing stories about the Port of Mokha, this ancient port in Yemen called Mokha. Most people don’t know that there’s a port called Mokha. So they told me about the Port of Mokha, and when I went back in 2013 to start this project, I’d tell my family, “I just want to see how this works out, I think there’s something cool over here. I’m not going to lie and say I had this master plan to start this huge business, just wanted to work with coffee. Just kind of happened as I went.

Your story has a darker component too, as you mentioned. Did you feel it was important to tell this story as a Muslim American, and particularly in this political climate?

For me, the two big things for me in this book are, one, the story of coffee — everything we eat and we wear and we use, they come from somewhere that someone produces it, and with coffee, there’s the reality of people working really hard to produce our coffee, and if we’re not careful in how we source our coffee, people can get exploited for that.

What do you hope readers take away from your and Dave’s portrait of Yemen?

I hope people can understand that this country is more than what’s in the headlines of Fox News. It’s a beautiful country with rich history, and one of the things the country did is it brought coffee to the world, from this port. Particularly, I want them to understand that Dave did an incredible job going through that. There’s parts of this book that are really wonderful and there are parts that aren’t so wonderful — getting into the war, to airstrikes, escaping on small boat on the Red Sea. You hear all these stories of people who leave these long sea voyages and go into Greece and Italy. You don’t want to leave the land, to go by ocean if they have no other choice. Looking back, what I did was stupid and crazy, but I had no choice and I made it here. I hope people can see that story of coffee, and the story of people around the world — they all have these difficult realities, but I hope that through this book, they can understand the reality of being a Muslim American and being someone who is between two countries.