Meet Georgia Gilmore, the cook turned activist who fueled the Montgomery Bus Boycott with her Southern cuisine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Netflix's "High on the Hog" celebrated Georgia Gilmore's contribution to the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Gilmore created the Club from Nowhere, which sold meals that raised money for the 381-day resistance.

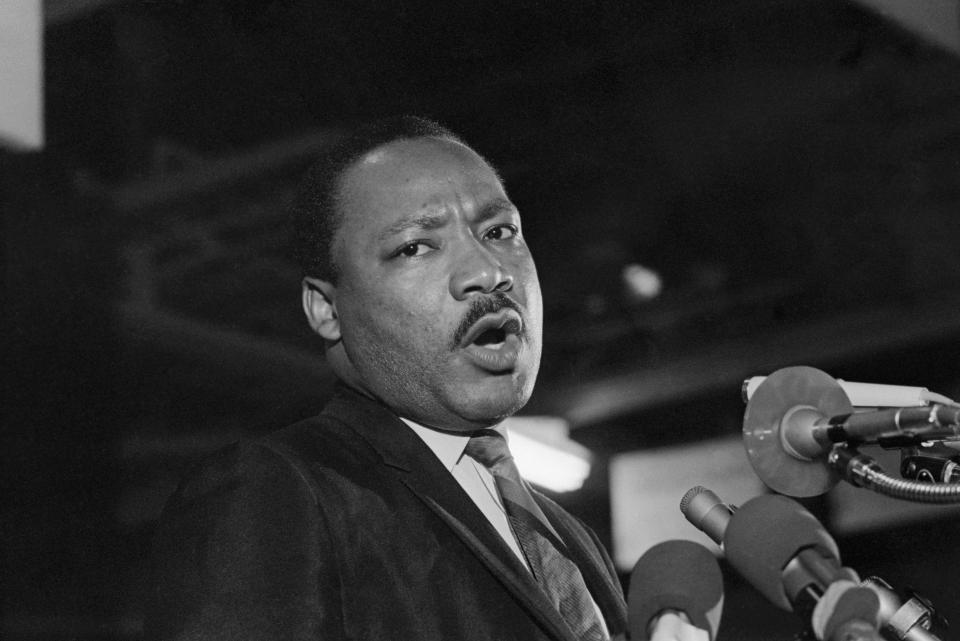

She later opened a restaurant in her home with the support of Martin Luther King Jr.

Georgia Gilmore was cooking in her Montgomery, Alabama, home in December 1956 with gospel music playing in the background when a radio announcement declared the Montgomery Bus Boycott was over.

Gilmore recalled the monumental moment during a 1986 interview with PBS' "Eye on the Prize." It took place just one year after activist Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man in Alabama's capital.

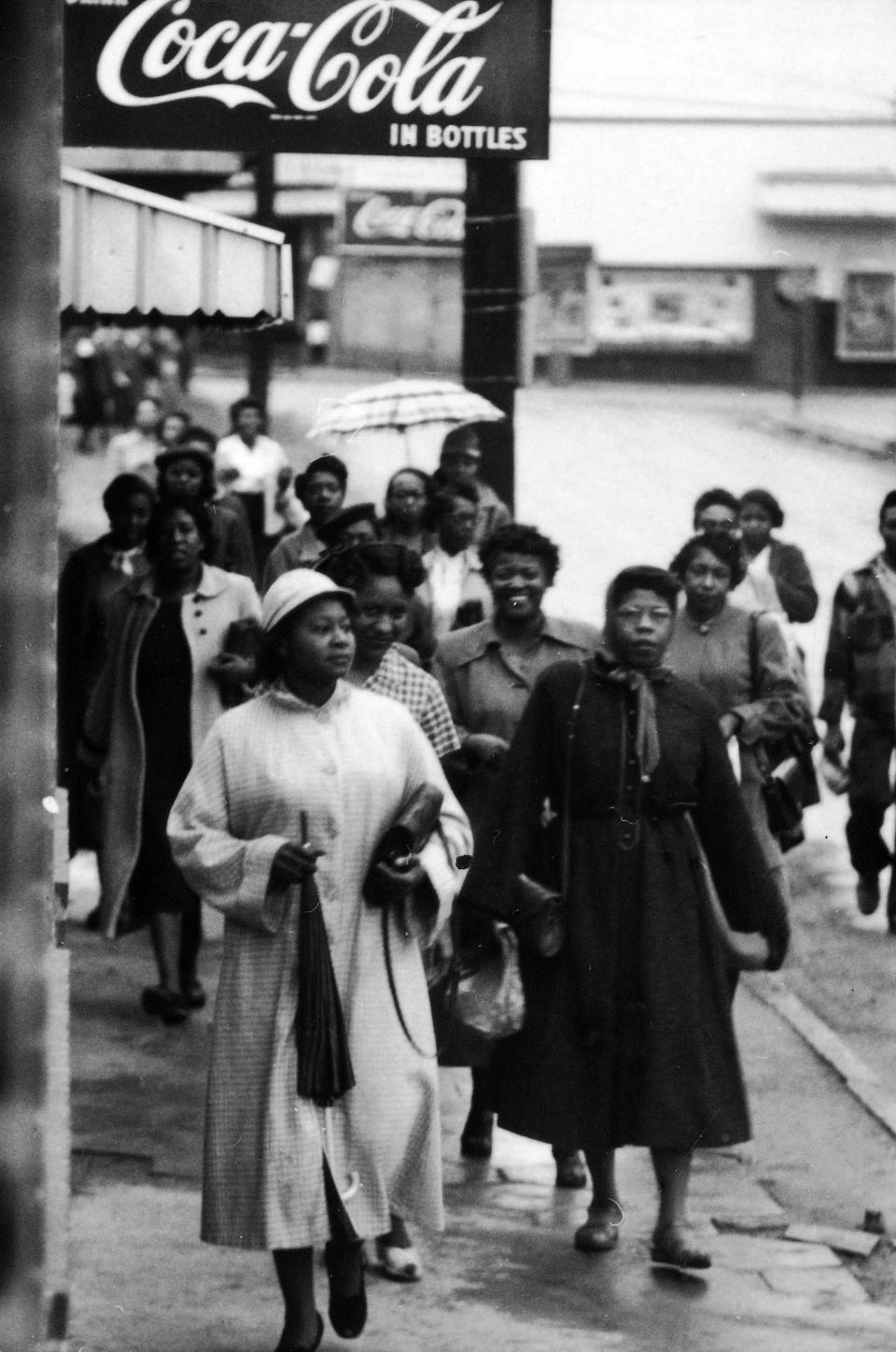

Parks' arrest inspired the city's Black community to boycott the public bus system for 381 days (December 5, 1955 - December 20, 1956) — a feat that would have been impossible without Gilmore. The boycott is considered the first large-scale demonstration against segregation in the US, per History.com.

During season two of Netflix's "High on the Hog," her legacy is highlighted when host Stephen Satterfield discusses how food and social justice are often intertwined. In episode three, Satterfield and Back in the Day Bakery owner Cheryl Day reminisced on Gilmore's undeniable contributions.

"All across the country, the civil-rights movement was being fed by chefs and bakers who met the moment. Not just by feeding the movement, but by funding it," Satterfield said.

Gilmore was subjected to repeated instances of racism before the Montgomery Bus Boycott

John T. Edge wrote in "The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South" that Gilmore was born in Montgomery in February 1920, according to a 2019 report by The New York Times. Edge added that Gilmore, one of seven siblings, worked at the National Lunch Company restaurant when the boycott began.

Gilmore and her fellow Black Montgomerians were often subjected to repeated instances of racism in the South. The NYT reported that Gilmore was kicked off a public bus in October 1955, two months before Parks' arrest, because she refused to enter through the back door.

Even after the boycott ended, Gilmore continued to face — and fight — racial discrimination. In 1957, she fought for her son's freedom after police arrested him for walking through a whites-only neighborhood, per the outlet. In another instance, she confronted a white store clerk who refused to sell her grandson bread and a box of detergent by taking his pistol and hitting him with it, the NYT reports.

She joined the Montgomery Bus Boycott after attending a community meeting about Rosa Parks' arrest

Gilmore told PBS that a meeting of Black community members was called at the Hope Street Baptist Church following Parks' arrest. That night, attendees — including Martin Luther King Jr. — swore they would not ride the buses beginning on December 5, 1955, until they gained equal rights.

Gilmore had concerns that some Black community members wouldn't join the boycott, but she was proven wrong. About 5,000 people attended the meeting, according to the outlet.

"It was really surprising," Gilmore said in the PBS interview. "We thought, maybe, some of the people would continue to ride the bus. But, after all, they had been mistreated and been mistreated in so many different ways until I guess they were tired and they just decided that they just wouldn't ride."

According to History.com, about 40,000 Black bus riders, who made up most of the city's riders, participated in the boycott on the first day.

Gilmore founded the Club from Nowhere, which sold meals and desserts to help fund the boycott

Black Montgomerians rallied together during the boycott in several ways, including staging protests, holding meetings, and launching a carpool system to help people get to work without public transportation. Each effort required money, which is where Gilmore came into the picture.

Recognizing her skill in the kitchen, Gilmore volunteered to prepare and later sell food out of her home to help cover costs. She told PBS that other local women soon joined her, and she founded the Club from Nowhere.

"In order to make the mass meeting and the boycott be a success and the carpool running, we decided that the peoples on the south side would get a club and the peoples on the west side would get a club," Gilmore said. "We decided that we wouldn't name the club anything. We'd just say it was the Club from Nowhere."

The NYT reported that the Club from Nowhere sold fried fish, pork chops, lima beans, fried chicken, and baked goods like pound cakes.

According to a 2018 report by NPR, the Club from Nowhere's profits went toward car insurance, gas, wagon and vehicle repairs, and more. Gilmore told PBS they also collected monetary donations from community members who couldn't attend the meetings.

Gilmore added that the club raised as much as $200 a week, "which was very nice of the people because so many of the people who didn't attend the mass meetings would give the donation to help keep the carpool going."

Gilmore was fired after participating in the boycott but pursued a new path with encouragement from King

The NYT reported that Gilmore was still working at the National Lunch Company when a Montgomery County grand jury indicted King for his role in the boycott in February 1956. However, Gilmore decided to testify on King's behalf, leading to her being fired.

"All these years you've worked for somebody else," King told Gilmore, per Edge. "Now it's time you worked for yourself."

Gilmore opened up a restaurant inside her home that served both Black and White patrons with the help of King, who gave her money to purchase necessary supplies. Edge wrote that prominent figures like Presidents Robert F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson were among her guests.

She continued her activism after the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended in December 1956

The United States Supreme Court desegregated public buses in November 1956, and King ended the boycott one month later.

"We felt that we had accomplished something that no one ever thought would ever happen in the city of Montgomery, and being able to ride the bus and sit any place on the bus that you desire was something that hadn't ever happened before," Gilmore told PBS.

The NYT reported that Gilmore continued to fight against racial injustice during her life, including in December 1958 when she was part of a class-action lawsuit to desegregate local public parks.

Per the outlet, Gilmore died in March 1990 at the age of 70 due to peritonitis. She died while preparing a meal to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery. Her food was served to the mourners, according to the NYT.

Read the original article on Insider