Meet the Cirque du Soleil Veteran Who Taught ‘The Last of Us’ Infected How to Move

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Back in April of 2020 — before the video game he co-created, The Last of Us, was a smash HBO series and was simply a cultural phenomenon on its own — Neil Druckmann set a long fan-debated topic to rest. After a Jeopardy clue about the game referred to its Infected (people afflicted with the fictional, widespread cordyceps brain infection) as “zombies,” Druckmann tweeted, “I mean…they’re not zombies” (before adding that the game show reference was still cool). Fast forward a couple of years, and the Infected are more vividly imagined than ever on The Last of Us, an Emmy frontrunner as balloting begins. And if it’s especially clear now that they are, indeed, not zombies — and instead clearly humans trapped by an invasive, deadly fungus — one man deserves particular credit. Over the course of season one, movement choreographer Terry Notary coached a group of 50 stunt performers, helping them transform into the Infected after immersing themselves in a “boot camp” of sorts in which they learned a technique he’s developed over years of conceptualizing movement onscreen. That work reached a stunning apex in the Infected influx of episode five, “Endure and Survive.”

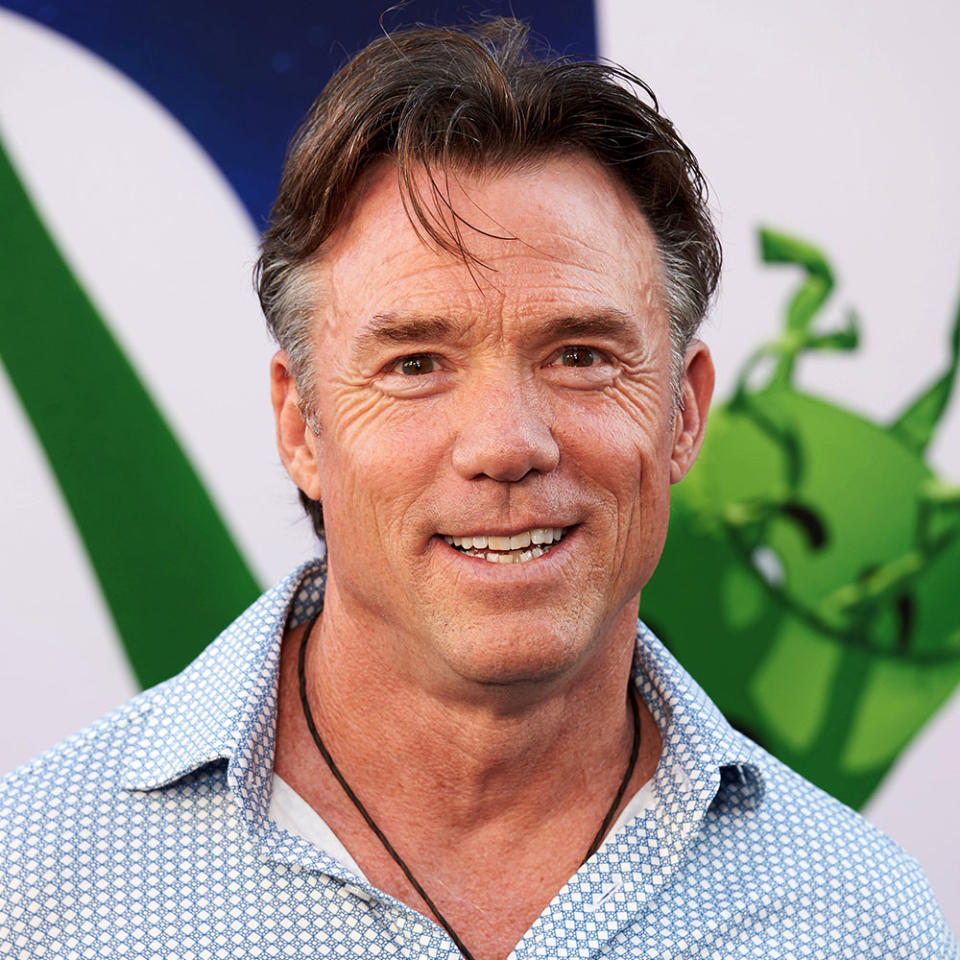

Speaking to Notary — whose most memorable onscreen appearance may have been his hilarious/disturbing simian turn in Ruben Östlund’s The Square — it’s easy to see why he was able to develop that cohort into episode four’s terrifying horde. A former gymnast turned Cirque du Soleil performer who found himself working in film almost by accident, Notary exudes an energy that’s part go-get ’em coach, part beatific spiritual leader, and he describes his work on The Last of Us more as existential quest than incredibly taxing physical feat (though, yes, he acknowledges it was that, too). He spoke to THR about finding the humanity of the Infected through movement — and how one very profound interaction with a chimpanzee more than two decades ago set him on a path towards The Last of Us.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

'The Last of Us' Co-Creator Says Matthew McConaughey Was in Talks to Star as Joel

How HBO Lost 'Yellowstone' to Paramount: "You Can't Make This S*** Up"

'And Just Like That' Boss on Samantha's Cameo, Aidan's Return and the Evolution of Che

Your own professional journey to becoming an in-demand movement choreographer was an unusual one. How did you get started, and how did you ultimately arrive in the world of film?

I started as a gymnast and went to UCLA, and right after that I got called from Cirque [du Soleil] saying, “Hey, come and audition.” So I joined Cirque and did that for four years — I was in the original cast of Mystère. Then my wife, who I met in Vegas, got a job as a Rockette, so we moved to New York and I became a photographer and was directing circus shows at the same time and performing at the Met[ropolitan Opera]. I was in my limbo zone like: what am I gonna do, what am I gonna be? And then Ron Howard’s company called me and said, “Do you wanna come out to L.A. and work on a film called The Grinch?” Like, yeah, I’m comin’ out!

He brought on five of my friends from Cirque, and we had about five weeks to play around in Whoville, and what [Howard] liked he said he’d put in the movie. When it came to coaching the extras, I just figured I’d help them like I would have in the circus. And Ron Howard saw that like, “Hey, what’s he doing?” “Oh, he’s teaching the extras movement…” “Call him into my office…” I thought I was gonna get fired — like, dude, you’re gone, man! But he said, “I like what you’re doing, and I want you to teach the whole cast. We’ll give you a soundstage and we’ll call it Who School.” I came up with a stupid list of everything I needed — spring floors, unicycles, treadmills, all kinds of mats, the list went on and on — and a week later, it was all there.

And then they called me for Planet of the Apes and asked, “Hey, can you do Ape School like you did Who School?” “Sure, I can do that!” And that eventually turned into, “Can you do superheroes?” And it just became a thing where the more I taught, the more I learned. Seeing the actors’ blueprints, what their habits are; I’ve developed my own technique to get through that. I call it “deconditioning,” pointing out all the things that are social behaviors we’ve been conditioned to [use]. When you break all that down and wipe it away, you can start from a clean canvas — the neutral body, and that’s what you need to create something original.

Did you take particular lessons away from the Planet of the Apes movies that helped you develop that technique?

For Planet of the Apes, at first I was trying to imitate apes. And I just kept asking myself, why is this not working? Then I got to work with two chimpanzees, Jacob and Jonah, and Jacob and I became friends. He was special. He jumped in my arms one day before we were going to rehearse, and he looked in my eyes, and he literally looked into my soul. I was like [gasps], “Oh my God, I see you!” He was looking right into me. I freaked out. It was a life-changing experience. He taught me about vulnerability, about gravitas, about strength in vulnerability, openness, being like a child, power. All at once.

I realized that if I can teach that, then that is my higher purpose in this world. You can teach people about who they are, where fear comes from, why it inhibits us and we let it become true. That’s the nemesis of acting; trying to mask or disguise fear or hide it, or decide what the end goal is before you get there. I really embrace the idea of embracing fear and using it as fuel to allow us to go into the unknown. If you have a loose idea, the path will be organic and it won’t be acting; it’ll be being. That’s basically what I learned from an ape.

I’m struck by what you said about not imitating an ape but becoming one. When you have a real-life example of what you’re trying to emulate, that’s one thing — but when you’re coaching an actor in becoming a fictional being, like one of the Infected on The Last of Us, there’s the added challenge of not just acting “like a zombie.” And it’s very clear, through their movement, that the Infected were once human, and maybe still are in some way.

Exactly right. They’re trapped within themselves, looking out from inside from some distant place. There’s’ an intelligence to them. They can’t just be bad guys, you have to feel sympathetic to them a bit.

How did you start to think about what their movement style would be like? Did the showrunners give you a sense of something they wanted?

They gave me all kinds of reference videos for the game, and that was pretty much it. I had to pay homage to the game, and I watched the game and the play, but at a certain point it was enough; I didn’t need to see any more. It was about creating chaos but as a cohesive group. I was thinking of how birds flock and move in ebbing and flowing patterns, but more in this chaotic, broken cadence, so it felt like in the chaos there was some interconnectedness. When I started working with the actors, I wanted to create a one-minded mentality. When one person moves, the whole group moves. No one led, no one followed; there was no ego or self-separation amongst each other. I wanted to explore the idea of how intelligent the cordyceps is, how [the Infected] can talk to each other through their roots, how they have this higher intelligence really, an ability to communicate without words, rather than being these mindless zombies. There was this otherness that made them feel dangerous in their collective camaraderie.

You had ran an Infected “bootcamp” to train the actors playing them. What exactly did that entail?

It was about four and a half weeks we had everybody preparing — but that was after a crazy month of casting, like [across] all of Canada and narrowed down to 50 people. I went through hundreds and hundreds of videos, then had Zoom calls with each person, saw what they were about, then met them. It was a long process just to get that core group I was going to work with, and then the training started.

At first it was just, “Everybody sit in a chair.” Everyone’s used to working really, really hard and being diligent, and it was about undoing that, getting back to breathing, sitting, presence. It was mind-blowing for a lot of people to start being present like that and just allow it. You just dissolve away, and the next thing you know, you’re going, “I gotta figure out who I am.” It’s so simple but so difficult. Then everyone’s one group, and we’re in it, and we can start the choreography, the techniques and exploring the broken [movement] cadence and the angles and the tempos and arrhythmic sensibility that would just surprise you into making mistakes.

We’d go out on these fields — I had this huge double soccer field — and we’d do a big group warm up. Start with group exercises, flowing and moving through piles, then breaking off from the piles and working with each person individually. Building a little village, where I’m in the trenches with them.

Were the actors you cast typically coming from some kind of dance or movement background?

Stunt background. All stunt players. Cause we needed them to jump over cars, come out of holes, quadruped, get hit, take shots. Heavy duty. Some are great movers, some are not. Some guys were incredible at running and just breaking through. Some guys were great at just hitting these positions on the ground when they died — doing that last sort of digging in. Some were just great at flowing as a group. Some guys were great at just taking car hits! [laughs].

We learn over the course of the season that there isn’t just one kind of Infected; there are varieties with different defining characteristics. Were you figuring out how movement distinguished them as well?

Yeah. The more evolved they became in their infected state, the more removed they became; the more they lost the conscious self that’s looking out going, “Help me! I’m stuck in here! I can’t control what’s going on here, I’m being taken over!” All the way to just being gone, like the Bloaters.

It seems like really physically taxing work….

It was freezing cold, and most of those shots were at night. It was pretty uncomfortable for those guys.

How did they take care of themselves?

Well, the guy at the hotel we were staying at would keep the bar open early in the morning, so when we got in at 7 a.m., that helped! (Laughs.) And then we’d have Segway races, that helped too. But yes, we took care of ourselves. Lots of foam rollers, lots of stretching the next morning, lots of, “Okay, how hard are we going today?”

Will you be back to work on the movement for season two?

I don’t think so, because I’m busy this year. I’m working on like five projects right now: two films in India that I’m directing action sequences on; another big series for television, with a showrunner whose work I really love; a film in England; and a Disney show in the States I’m excited about. I’m pretty booked up and busy!

It was a moment in time, and I loved it. And it was great, but [that team] knows it now, and they’ll pull from that pool [of actors who already trained]. I mean, they did their own training! I just guided them. Those guys worked so hard on those scenes — you see it as one four-minute scene, but that took two weeks to shoot, all night every night. Everyone pulled their weight and then some. But we all felt like, “This is gonna be a good show. This is gonna rock.”

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Tom Holland Breaks Free: Talking Zendaya, ‘The Crowded Room’ and the Future of Spider-Man

Critic's Notebook: Jerry Springer Didn't Just Reflect Our Debased Culture — He Helped Create It