The Meaning of Lil’ Kim

Throughout hip-hop history, women rappers have often been diminished and tokenized by the genre’s male-dominated establishment. The Motherlode serves as a comprehensive corrective: The book highlights more than 100 women who played an integral part in rap’s evolution, from early pioneers like MC Sha-Rock and Roxanne Shanté to underrated boundary breakers including Bytches With Problems and Yo-Yo to modern stars like Azealia Banks and Cardi B. Author and Pitchfork contributing editor Clover Hope tells each of their stories with clarity and a deep knowledge, while vivid illustrations by Rachelle Baker and a series of pithy sidebars—including one called “Nicki Minaj Invented Color” that breaks down the chart topper’s loudest looks—convey hip-hop’s infectious sense of play.

This month’s Pitchfork Book Club features an excerpt from The Motherlode that chronicles how the iconic Brooklyn rapper Lil’ Kim set a sexually liberated precedent that artists have been following for the last 25 years.

Lil’ Kim

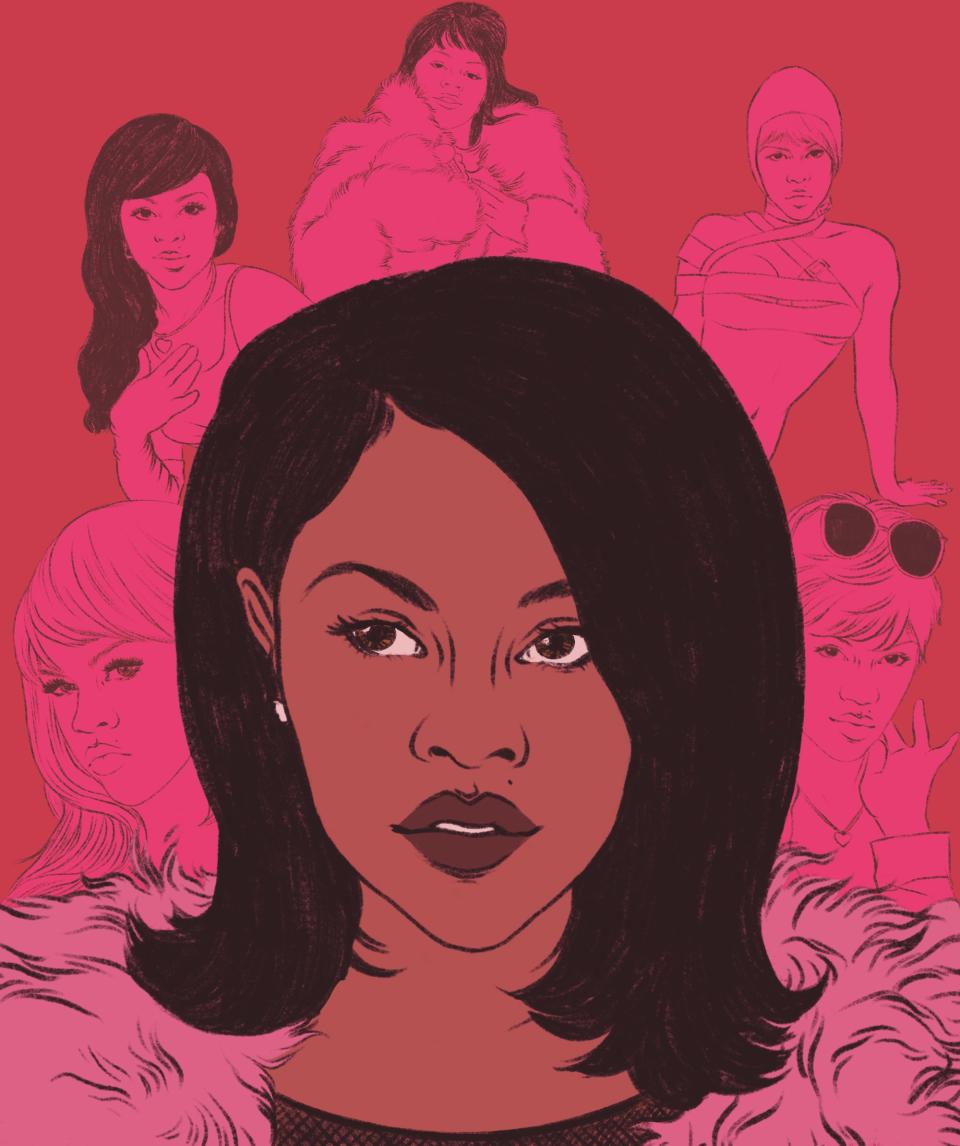

Lil’ Kim illustration from The Motherlode by Rachelle Baker © Abrams ImageThe defining image of Lil’ Kim’s career is a portrait of her squatting in a leopard-print bikini, an outtake from the photo shoot for Hard Core. Her mentor, the Notorious B.I.G., chose the photo for posters leading up to the album’s 1996 release, knowing exactly which pose to use. “He threw the negatives on the table and pointed to the one with my legs open and said, ‘That’s the one right there,’” Kim told XXL, 10 years later. Throughout the recording process, Biggie masterminded Kim’s image and content, telling her to soften her voice, for example, to sound less masculine.

Kim, at some point, decided to own that persona, becoming a dream girl men envisioned, rap’s ultimate sex symbol, praised for both her skills and her salesmanship of fucking. Before Kim, the top-selling women rappers—Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, Salt-N-Pepa—had been all about challenging sexism in hip-hop. Kim brought a raw sexual energy to the genre and became the model for a generation of female rappers caught in a battle between owning their sexuality and exploiting it. She made the new concept of a female rapper—with a sexy visual to go with their music—not a choice but a necessity.

Before Hard Core hit the streets, Kim ran with Junior M.A.F.I.A., the nine-deep Brooklyn crew assembled by Biggie. The first song she ever rapped on, 1995’s “Player’s Anthem,” released when Kim was 17, established Junior M.A.F.I.A. as the latest formidable rap squad and set the tone for Kim as a soloist. Hardly anyone questioned her talent or ability. She raps so hard on the Hard Core track “Queen B@#$H” that she runs out of breath by the end of the verse: “Sippin’ Zinfandels up in Chippendales/Shoppin’ Bloomingdales for Prada bags, female Don Dada has...” Still, fans and critics wondered how much of Kim was really Biggie, which made it hard to talk about Lil’ Kim without talking about him.

“Just being the girl in the group was majestic,” says Kierna Mayo, the founding editor-in-chief of Honey (Kim covered the magazine twice). “Kim was four-eleven. She’s tiny. It made her that much more profound, when you juxtapose the largeness of Big against Kim’s small frame. He was a Svengali of sorts, and she was his loyal concubine. And it was dramatic and sometimes tragic to see.” A week after Hard Core’s release, another rapper, Foxy Brown, released her own debut album, Ill Na Na, creating a double dilemma: Kim and Foxy’s new blueprint for success liberated women’s dirty thoughts, but it was all about male fantasy.

In 1996, Kim appeared on an episode of BET Talk with Tavis Smiley, alongside Luke Campbell of 2 Live Crew fame, to discuss the raunchiness of their lyrics. “It’s my image. If people didn’t see this on me, they probably would walk past me,” Kim said on air. “A lot of men flock to me, they flock to my poster. They flock to my personality as well.”

Kim’s traumatic backstory played into her image. After her parents divorced, a move with her mother to New Rochelle begat a period of homelessness. One of Kim’s favorite books was Alice Childress’s novel Rainbow Jordan, because she related to the foster-child protagonist.

Kim later returned to live with her dad (and her brother) in Brooklyn, where her father, a former military member, ran a strict household. He spoiled her with designer Gucci threads, to the envy of her classmates. But she and her father argued constantly. (Kim once stabbed him with scissors.) Kim eventually left home, couch-surfing with friends and transporting drugs for dealers as her profession. Everything changed after she ran into Biggie on Fulton Street in Brooklyn and rapped for him. This was the man who, she later rapped, “swooped a young bitch off her knees” and served as her mentor and lover.

Lil Kim, Sean Puffy Combs and Notorious B.I.G

Jacob York, the former president of Kim’s label, Undeas Entertainment, met her on St. James Place, Biggie’s home base. “I remember she had black spandex on and these boots and she had a hat on her head, ’cause her hair was short, and she had a halter top on. She just started rapping, and it was this very deep voice,” York says. “She wasn’t as sexual on the Junior M.A.F.I.A. album as she ended up being on her album. What we kept presenting to her were ways to feminize herself more. By the time it got to Hard Core, she began to develop a sound.”

Biggie heard the bass in her voice, too, and reshaped it. The goal for them was to soften her tone. They were building a perfect rap girl. “When I first met Lil’ Kim, her aggression was Fredro from Onyx, and Big hated it,” says Lance “Un” Rivera, who co-founded Undeas with Biggie. “When we were making the Junior M.A.F.I.A. album and she did ‘Backstabbers,’ he heard the tone in her voice and said, ‘This is it.’ He said, now you appeal to my manliness from a music standpoint.”

Kim and Biggie’s tense relationship is part of hip-hop lore. They fought in a recording studio elevator. She watched him marry R&B singer Faith Evans and date Charli Baltimore. Kim became pregnant with Biggie’s child and had an abortion while recording Hard Core at the same time that she was working on Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s debut album, Conspiracy. Her subject matter, as a result, skewed dark (she rapped a lot about death and drugs). York says they had to stop recording because the music was getting “darker and darker.”

“It was kind of a sad album at that point, ’cause she was going through that personal relationship with Biggie,” says York. “If you listen to the original [Hard Core] album, there’s no Lil’ Kim verse on [‘Crush on You’]. It’s just Cease. Because I just said, ‘Fuck it, we putting this single on it, and we gonna use it to propel his career ’cause I’m not gonna get anymore music out of her.’”

Her image, through Biggie and Rivera, was all about the fulfillment of desire. “My strategy was [consistent] when it comes to Kim: She wasn’t the wife. She was the high-end side chick to drug dealers,” says Rivera. “We placed her in a world that we were living in, and it was: You wear all of the finest things because the number one drug dealer, you’re his side chick, and he buys you everything. It’s all driven by the male hormones, the male ego, the fantasy. It’s not about love. It’s about being nasty.” This was an obvious issue, having a cast of men controlling her image, which only fueled the myth that Biggie was writing most of her lyrics.

Kim’s collaborators have all but confirmed that while Biggie coached her on cadence and flow, she wrote most of her own material. Rivera says of Hard Core, “She wrote the majority of the album. Biggie wrote a few songs. All of the singles that she’s ever been on that were hits, she wrote those verses herself.”

The late rapper Prodigy said he saw Kim write the entirety of her verse for Mobb Deep’s “Quiet Storm (Remix)” in the studio. Jacob York says he sat in on most of the studio sessions for Hard Core. It was hard for people to imagine that a woman with access to a gift like Biggie wouldn’t have him writing all her lyrics. But that assumption was ultimately a sign of rap’s low expectations for women.

“She wrote her singles. ‘Get Money’—she wrote that motherfucker. She wrote ‘No Time,’” says York. “It was more about her being taught how to rap. ’Cause Kim always understood what to write, but sometimes she would go places. She goes back to that girl on the block with that deep voice.”

York breaks down the math. “She wrote another verse to ‘Get Money,’ and Big was like, ‘That verse is trash,’” he remembers. “So what he did was, he rapped his verse, she studied it, and she came [up] with a verse. He helped her with the first, like, eight bars of that [and said], ‘Yours should match mine.’ That little part after ‘You wanna get between my knees,’ that was the Biggie influence. After that, you can tell that the flow completely changes. And that’s Kim all at her own devices on that record.”

York says he and Rivera wrote the porn star reference in Kim’s verse on Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s “I Need You Tonight,” where she name-drops Vanessa del Rio. But for “Big Momma Thang,” he says Kim wrote the references to two famous black mid-’90s porn stars, Heather Hunter and Janet Jacme. “I don’t think it was that we forced the words into her mouth as much as we emancipated what she felt she could and couldn’t do. Kim is what you heard in those records.”

But Kim was shaped by men who got to dictate how she would be marketed. If she was constantly being molded and if being any other way than sexy wasn’t a viable choice, she couldn’t have a complete sense of power. What’s remarkable is how rappers like Kim and Salt-N-Pepa, despite being under the guidance of male producers, still used their voices as tools of liberation.

Although Biggie’s involvement will always be a point of contention, he is a big reason her best album was her first one. What Kim accomplished on her own, despite his input, is still monumental. Her lyrics (“No licky licky, fuck the dicky dicky”) became shameless mantras for women who were both discovering and engaging in sex. “If you look at the adult sex business from the beginning of time,” says Heather Hunter, “the whole idea was to open the doors so our culture could embrace it and, as African-American women, to be proud of your sexuality and be proud of your temple. To see Lil’ Kim, the Wanda Dees of the world, the Foxy Browns, to see these people open these doors and embrace it and move forward, to me, was a beautiful thing.”

When asked about control of her “hard-core” image, Kim told bell hooks in a Paper interview, “We all had a lot to do with my career; we all have our input. I would say that it was me who just started it, because I would have to do it and feel comfortable, you know what I mean? You can’t really just make someone into something and it works all the time; that person has to be a natural.”

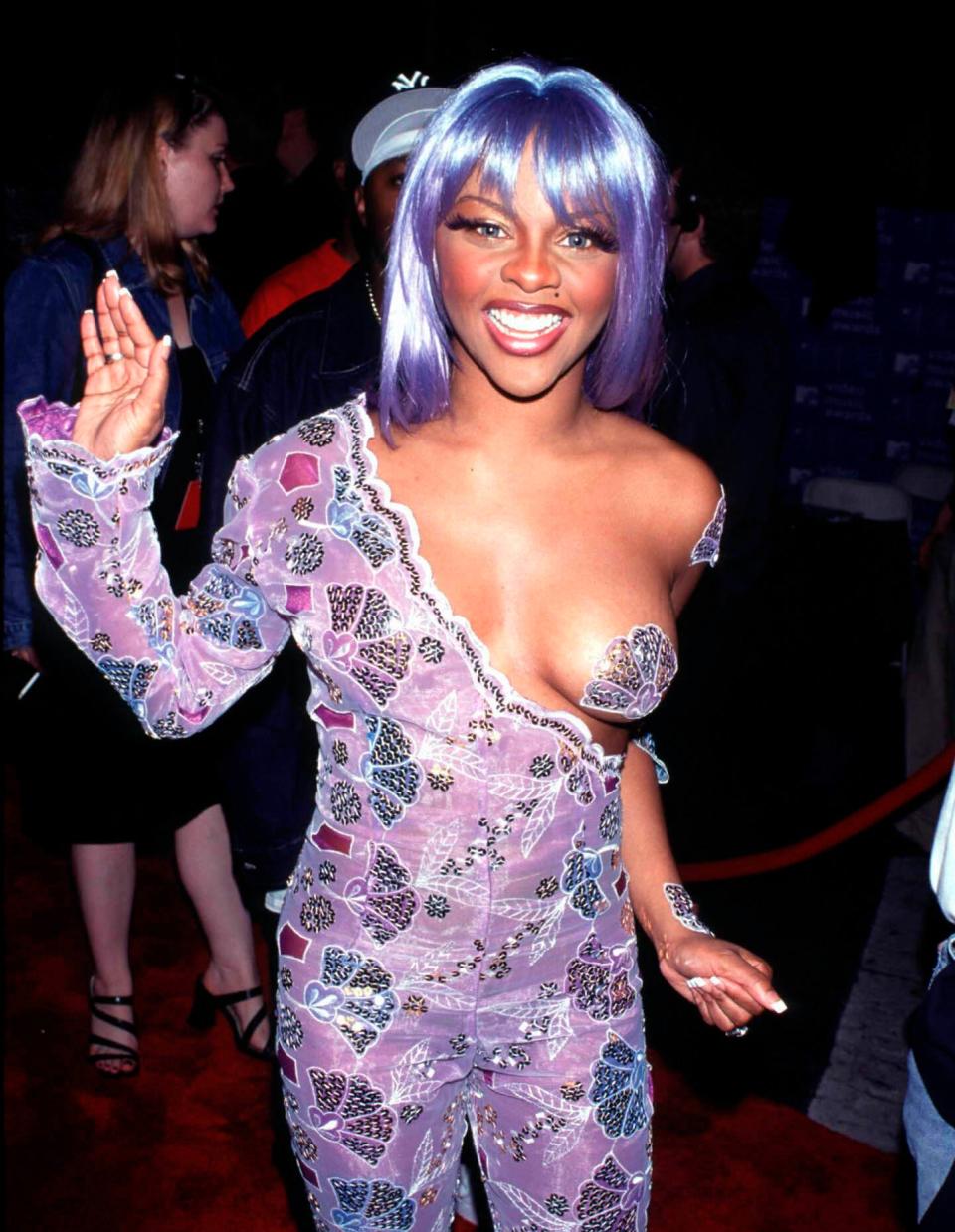

Some of the control she might’ve lost elsewhere, she regained by crafting her own designer image as a black Barbie. Lil’ Kim would wear anything anywhere to stand out: a red leather biker outfit with matching helmet, a sheer I Dream of Jeannie gown with a mask, full-on lingerie, mink wrist cuffs, a purple seashell pasty on one lonely breast. During photo shoots, she would do anything: dress like a blow-up doll; transform into a living, breathing Louis Vuitton accessory; and, yes, squat in a bikini made by designer Patricia Fields. She wore vibrant furs and 1950s-housewife wigs in the video for her single “Crush on You” (the theme of which was inspired by The Wiz). She rocked hot pants while riding a World Trade Center escalator in the video for “No Time.”

MTV Video Music Awards At The Metropolitan Opera House At Lincoln Center

“Everybody wanted to dress her, photograph her, put makeup on her. Annie Leibovitz, Bruce Weber,” says Christina Murray, the head of black music publicity at Atlantic Records for Kim’s first two albums. “You have artists that would say no, but Kim was not like that. ‘Kim, they wanna do your hair like this.’ Kim was never, like, ‘No.’ She saw what they saw in her, and she was open to all those things.”

Kim’s stylist, Misa Hylton Brim, made customized looks and gave Kim the shock value needed for fashion to embrace her as a pliable muse. (The furs and jewelry Kim wore in “No Time” came from Brim’s personal collection.)

“Because Kim’s lyrics were risqué and because at the time she was in a relationship with Big, Un’s idea was to create her image as the mistress of rap. And he gave us the freedom to take that concept and run with it,” says Hylton Brim, who saw Kim’s style as a reflection of Kim’s inner self, which said it was okay for women to want to dress like a doll, or drape themselves in rings and things. It was okay for women to create fantasy.

“If Kim had not taken the risks in music and fashion that she did, female rappers today would probably still be underplaying their looks just to legitimize their music,” says Brim. “Kim created another lane, allowing women to shape their own images and express themselves in any way they want through style. We don’t have to be just one way as women. We get to choose what we wear and how we wear it.”

The press framed Kim’s career with varying degrees of praise and concern. For its February 1997 magazine cover, The Source featured Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown back-to-back, with the cover line “Sex & Hip-Hop: Harlots or Heroines?” For its October 2000 issue, Ebony published a piece about Kim as an American sex symbol, asking, “Is Mainstream Ready for Lil’ Kim?” Essence put Kim on the cover that same month, with the line “The Big Problem with Lil’ Kim.”

There were women who found her image offensive; others felt freed by it. And both men and women wanted the fantasy. For women writing about hip-hop, discussing Lil’ Kim was like deciphering a quantum entanglement. She seemed to exist solely as a topic for debate about hip-hop’s worst traits, not just as a medium for sexual liberation; she was a subject to advance conversations about misogyny in rap and a reflection of black girls’ insecurities. It wasn’t just her image, but her physical exterior, which changed over the years; she has admitted to plastic surgery and once had a second nose job after her boyfriend assaulted her. These complexities made her fascinating and also contributed to making her a star. She wanted to be pretty, to be sexy, to be not Kimberly Jones, but Lil’ Kim. And by being Lil’ Kim, she looked to free herself and others.

Aliya S. King, a former staff writer for The Source, was in her early 20s and teaching history at a high school in East Orange, New Jersey, in 1996 when Hard Core dropped. She remembers the girls in her class dancing like Kim and wearing the same bright wigs. “They were definitely liberated in a way that I wasn’t,” says King.

“She reminded me of girls I grew up with who were all about the fashion, all about the boys, and those are the kind of girls who got talked about,” says Karen Good, who interviewed Kim for the September 1997 edition of Vibe. “There were rumors, and they were called all kinds of ‘hoes’ and ‘bitches,’ and they were just, like, ‘Well, I’ll be the best bitch.’”

Hard Core dropped when I was 13 years old, learning about sex ed through detailed anatomy books, YA novels, and Lil’ Kim saying, “I used to be scared of the dick/Now I throw lips to the shit,” which sounds like a coming-of-age story on its own. Kim’s music helped girls feel comfortable talking about sex. Most impressive, she was the world’s most tireless advocate of men eating pussy. She refused to settle for less and gave us Smithsonian-worthy lines about it:

“Lick up in my twat/Gotta hit the spot”

“No licky licky? Fuck ya dicky dicky and ya quickie”

“Got buffoons eatin’ my pussy while I watch cartoons”

“You ain’t lickin’ this? You ain’t stickin’ this”

“Only way you seeing me is if you eatin’ me”

“All I wanna do is get my pussy sucked”

Et cetera. This was language that changed the game; it was adult film refurbished as rap, which set a precedent for future artists like Khia and Trina.

“I remember that kind of language being liberating and exhilarating, and it kind of put all of us on blast, those of us who hadn’t felt free enough, during that time, to have these contradictions in our public persona,” says Kierna Mayo. “It just kind of blew everybody’s mind.”

After Biggie’s death in 1997, Kim’s subsequent albums became litmus tests for her ability and whether she could rap on her own and still sell. She could and she did. Think of her pussy-eating manifesto “How Many Licks,” featuring the thong man Sisqo and a music video that leans fully into Kim’s manufactured-doll imagery. Think of her professing to be a “black Barbie dressed in Bulgari” and rapping about deep-throating on her spastic single “The Jumpoff,” from her third album, 2003’s La Bella Mafia. While the precision wasn’t the same as with Hard Core, she could definitely rap on her own. Kim’s very public contradictions and the spectacle of sex around her allowed the rappers after her to take the most valuable parts of her blueprint and leave the rest. The fruits of her labor were seeded through rappers like Cardi B and Nicki Minaj, who modeled her colorful wigs after Kim’s (Nicki also recreated Kim’s squat pose early in her career, before they began beefing). Kim was, in every way, an experiment, a muse, and a sacrificial lamb.

The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop

$25.00, Amazon

Originally Appeared on Pitchfork