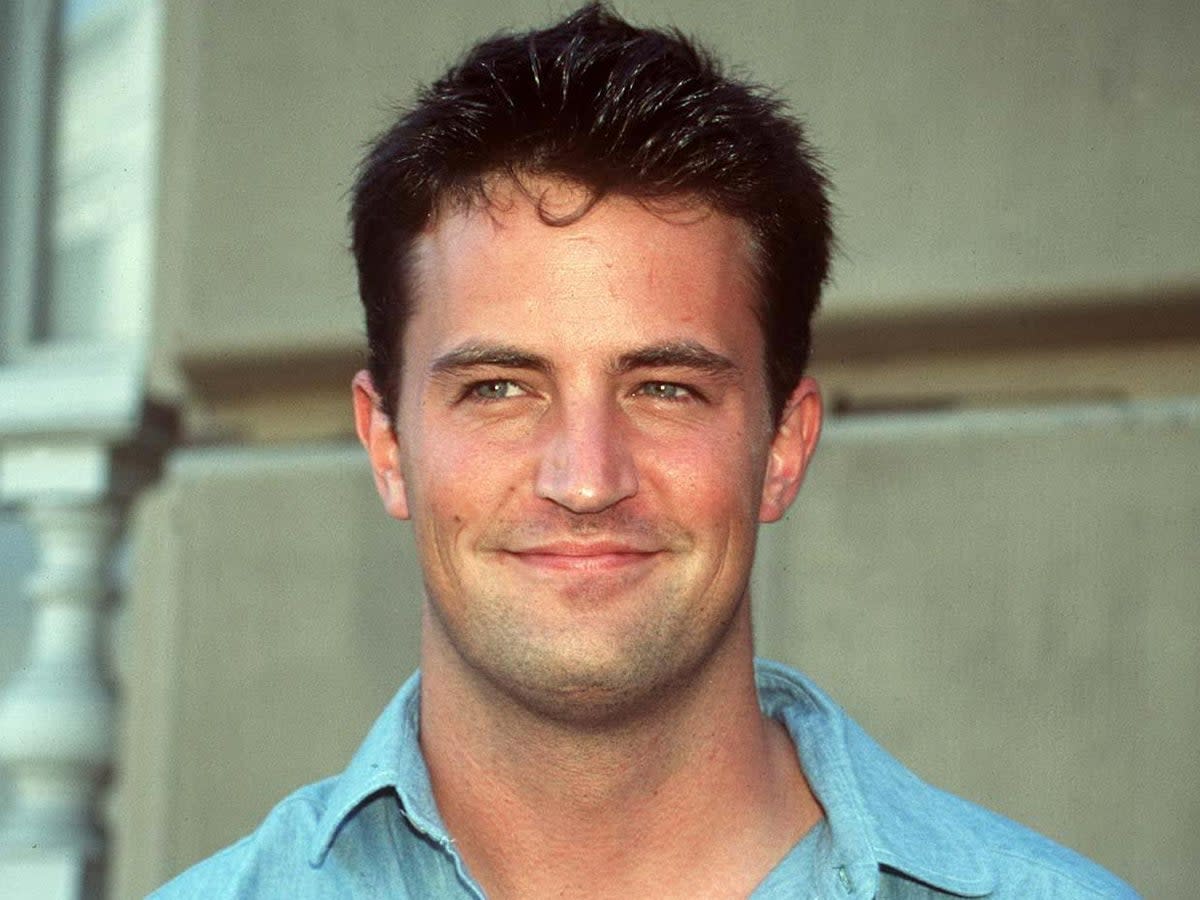

Matthew Perry, the comic genius who wore his big, bruised heart on his sleeve

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Matthew Perry was a teenager in Ottawa, Canada, he developed a dryly sarcastic manner of talking that was a big hit with his friends. At high school, he had discovered that he could use humour to get people’s attention – and attention and validation were what he craved. Muttering behind the back of a particularly belligerent teacher, he would say, “Could he be any meaner?”, to hoots of laughter.

Ten years later, reading the early scripts for Friends, a series about a group of twentysomething New Yorkers who lived in and out of each other’s apartments, Perry found a kindred spirit in the character of Chandler Bing, who used humour to send up his own insecurities and whose sarcastic one-liners – “Could she be more out of my league?” – would become his trademark.

During the casting process, David Crane and Marta Kauffman, the creators of Friends, had been struggling to find their Chandler, and were worried they might have to rewrite him. But when Perry auditioned, Crane would later recall, “We just looked at each other and went, ‘Oh my God, so the writing doesn’t suck. We just hadn’t found the guy yet ... Matthew came in and you went, ‘Oh well, there you go. Done, done. That’s the guy.’”

Friends would turn Perry – who died at his home yesterday at the age of 54 – into one of the most famous comic actors in the world. Along with his fellow cast members, who included David Schwimmer, Courteney Cox and Jennifer Aniston, he would also become one of the highest paid – at its peak they were each earning $1m an episode.

Each of the Friends struggled to adjust to their skyrocketing celebrity, but none more than Perry, who already had a drink problem when the series began – Aniston once told him on set that she could smell the alcohol on his breath – and for whom fame was not the salve he had hoped it would be. “You have to get famous to know it is not the answer,” he wrote in his memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing. “And nobody who is not famous will ever truly believe that.”

Published last year, Perry’s variously funny, candid and sad memoir was less the story of a glittering showbiz career and a gilded life than a tale of the epic struggle of a lifelong addict to keep the show on the road. Perry’s alcohol addiction soon expanded to take in prescription painkillers and opioids. Throughout his life, he reckoned to have attended 6,000 AA meetings, detoxed 65 times, and spent in the vicinity of $7m on rehab.

In the book, he detailed various near-death experiences, the most dramatic of which occurred when he was 49, with an “explosion” of the bowel, a result of chronic constipation caused by opiate abuse. After arriving at the emergency room screaming in pain, Perry underwent seven hours of surgery and fell into a coma that lasted for two weeks. “It’s kind of poetic,” he wrote. “I was so full of s*** it nearly killed me.”

Perry was always clear about where and how his problems began. When his parents divorced, his mother (a journalist who was press secretary to Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau in the late 1960s – Perry once beat up his son, the current prime minister Justin, who has paid warm tribute to his old schoolmate) stayed in Ottawa and remarried, while his father, a jobbing actor who also liked a drink, set up digs in Los Angeles.

From the age of five, Perry would shuttle between their two homes, travelling by plane alone with a sign around his neck that read: “Unaccompanied minor”. Thus began the feelings of abandonment and rootlessness that would plague him long into adulthood, and would lead him to sabotage his romantic relationships (he dated Julia Roberts and Baywatch star Yasmine Bleeth, and was engaged to, but never married, the literary manager Molly Hurwitz).

When Perry was a child, it looked as though tennis was his calling, as he became a top-ranked junior player. But then, at the age of 14, he discovered alcohol, which made him instantly charming and funny, a feeling he enjoyed considerably more than winning at tennis. At 15, he moved to Los Angeles to live with his father permanently, and decided to focus on acting; before leaving high school, he was already a regular on the comedy improv circuit and, by his early twenties, was landing parts in TV series such as Second Chance (which later became Boys Will Be Boys), Sydney, and 1993’s Home Free, in which he played a young journalist who still lived with his mother.

Perry’s commitment to a new pilot called LAX 2194 when he was 24, about an airport baggage handler, meant he nearly missed out on the auditions for Friends. At the time, Kauffman and Crane’s series was called Six of One; when Perry read the script, he knew he had to do it. “It wasn’t that I thought I could play Chandler,” he said. “I was Chandler.” When Fox mercifully declined to pick up LAX 2194 as a series, the role of Chandler was his.

Watch any Friends rerun now – the series remains wildly popular with successive generations through its availability on Netflix – and it’s clear that the whole cast were working at the peak of their powers. Nonetheless, it is Perry who nearly always stands out. His performance remains a masterclass in comic timing, his sharp one-liners nearly always delivered with a seam of self-loathing. Talking to Julia Roberts’s character Susie Moss, who recalls Chandler tormenting her at high school, he says: “Back then, I used humour as a defence mechanism. Thank God I don’t do that any more.”

Two years ago, the HBO special Friends: The Reunion gathered together the cast on the Los Angeles lot. A tired-looking Perry was last on set, prompting Matt LeBlanc, who played Joey, to exclaim, “Could you be any later?” Throughout the show, Perry was visibly emotional, and confessed that, while filming Friends in front of a studio audience, “I felt like I would die if I didn’t get a laugh – I’d sweat, have convulsions.”

It’s little wonder that the runaway success of Friends – the final episode, which aired on 6 May 2004, was watched by 52.5 million viewers in America (a further 8.6 million watched in the UK), making it the most-watched TV episode of the decade – would become a millstone for the actor, who spent subsequent decades trying, and inevitably failing, to match it through other projects.

Perry’s post-Friends work included the funny yet flawed Aaron Sorkin project Studio 60 on Sunset Strip, in which he played a screenwriter alongside Bradley Whitford (Perry had appeared as associate White House counsel Joe Quincy in Sorkin’s The West Wing). The show was cancelled after just one series. Another comedy, Mr Sunshine, conceived by Perry and in which he played the manager of a San Diego sports arena, was canned after nine episodes.

There were successes, too: Perry guest-starred in The Good Wife, and appeared in a CBS revival of The Odd Couple, which he also co-wrote, in 2015. But his biggest labour of love was his playwrighting debut The End of Longing, in which he also starred as a middle-aged alcoholic named Jack Perry, and which opened in London in 2016; reviews were mixed, but the show nonetheless had a successful run off Broadway. Though it wasn’t autobiographical, Perry said he had written Jack as “sort of an exaggerated form of myself”.

Throughout his career, Perry brought talent in spades and, after his 10-year stint on Friends, oceans of goodwill. Friends and co-workers have spoken of his kindness. One of them, the documentarian Jon Ronson, who directed him in an episode of Playhouse Presents, this morning recalled the actor as “extremely thoughtful and generous”.

Perry also went out of his way to help other recovering addicts, funding sober-living facilities such as Perry House in Malibu. But his own addictions continued to drag him down. By far the most poignant part of his memoir was when he bluntly revealed the desolation of a life lived “in a huge house, overlooking the ocean, with no one to share it with, save a sober companion, a nurse and a gardener twice a week”. Perry will be remembered not only as a remarkable comic actor, but as a man who was disarmingly honest about his frailties and wore his big, bruised heart on his sleeve.

If you have been affected by this article, you can contact the following organisations for support: actiononaddiction.org.uk, mind.org.uk, nhs.uk/live-well, mentalhealth.org.uk