‘Master Gardener’ Is Paul Schrader Playing With Neo-Nazi Dynamite

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A person sits at a desk, in a room so stark and tidy it might belong to a monk or a model prisoner, writing in a notebook. His inner monologue plays as a voiceover, drier than sandpaper; in this case, it’s a horticulture lecture about French and British gardens. If you were not aware that you were watching the opening shots of a Paul Schrader film, you’d think you were witnessing a parody of one. For 50-plus years, the legendary screenwriter and director has turned a stable of God’s Lonely Men into articulate antiheroes for the ages. They could be taxi drivers or Armani-clad gigolos, famous authors or anonymous gamblers, big-city drug dealers or country priests. These characters are connected by an existential turmoil that, more often than not, boils over into violence and self-destruction. They each have their own personal demons. They all have Schrader’s distinct voice.

His latest, Master Gardener, caps an informal trilogy of back-to-Bressonian-basics movies that have signaled not so much a return to form as an incredible late-act second wind. And though this story of a stoic groundskeeper doesn’t have the heft of Schrader’s 2017 masterpiece First Reformed or his 2021 restless royal flush The Card Counter, it’s still the sort of burrowing, brow-furrowing drama that forces you to reckon with big questions. Does someone’s past, partially buried or fully paved over, permanently pockmark their future? Is redemption possible when their moral compass has cracked and only been semi-repaired? And how far are you willing to walk in that person’s scuffed boots to find out?

More from Rolling Stone

Clarence Thomas' Billionaire Buddy Has a Vast Collection of Hitler Paintings, Nazi Memorabilia

'Transatlantic': The Daring Rescue of Jews From Nazi-Occupied France

How 'Avatar: The Way of Water' Turned Sigourney Weaver Into a Teenager

Narvel Roth (Joel Edgerton) tends to Greenwood Gardens, a lush oasis on the Louisiana estate of a rich woman named Norma (Sigourney Weaver, flexing some aristocratic entitlement chops). He’s a button-the-top-button kind of guy, his hair neatly trimmed and combed, his voice studiously devoid of inflection. There’s an institutionalized vibe around him, which suggests either military or hard time. When Narvel tries to pep-talk his team for an upcoming charity event, he comes within spitting distance of sounding inspirational; talking to Norma, he can be sarcastic (“It’s always fun to watching grown men in pastel pants outbid each other for a flower”). But this taciturn guy in overalls always seems to be carefully masking anything that might give away his thoughts or feelings. Narvel isn’t just a closed book. He’s a padlocked volume in a conspicuously plain brown wrapper.

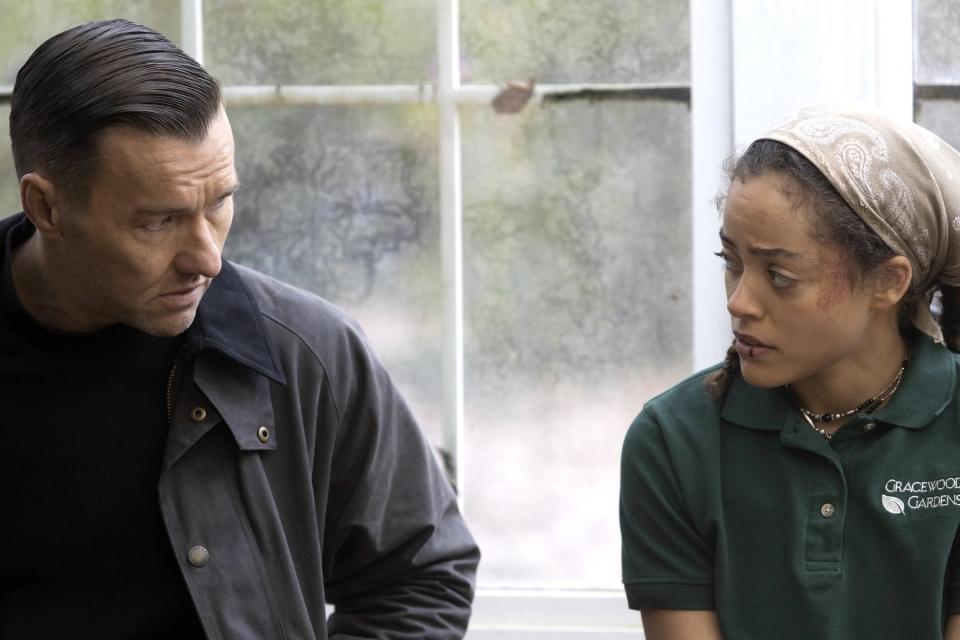

None of that stops Norma from dining with him and having sex — possibly consensual, definitely a power move on her part — with her blandly handsome worker once a week. Nor does it keep her from asking him for a huge favor: Her grandniece Maya (Quintessa Swindell) is in some trouble, and she needs to help this young woman course-correct. She wants Narvel to teach her how to maintain the garden and green up her thumb. Make her your apprentice, the boss tells him. It’ll give her structure. When Maya shows up, he does what he can to show this reluctant addition to his team the ropes. The relationship is spiky. Her addiction issues are a problem, though they aren’t a secret.

What is a secret is how Narvel ended up learning the art of nurturing plant life, which turns out to involve the Feds, and flipping on his old friends to save himself. And when this quiet man removes his shirt and reveals a torso covered with swastikas and white-power tattoos, you truly get a sense of how deep this man’s repression and history of violence goes. He doesn’t seem to harbor any animosity toward Maya, who is Black — there’s a tension between them, yet it’s more of the simmering sexual type. Still, you get the sense that lines are being crossed here. Some are unspoken (see: Norma’s attachment), some are obvious (the mentor relationship) and, once Narvel tries to use his F.B.I. case handler (Esai Morales, doing a lot with little screen time) to get rid of drug-dealer acquaintances of Maya’s, some are ethically dodgy.

Schrader knows he’s playing with dynamite here, throwing hate groups and age-discrepancy romances and hints of class warfare into this tale of a tightly-wound man coming undone. He’s also reluctant to light the fuse on these hot-button issues, which keeps Master Gardener from edging into exploitation territory yet makes you feel that he’s not interested in really exploring any sociopolitical aspects at all. They’re just there to make the stakes higher, to up the ante on this particular antihero’s journey. He’s not out to make a message movie by any means. But there’s a problematic murkiness that never goes away.

None of which takes away from the actors — the fact that Edgerton somehow delivers his best screen performance to date courtesy of a role that requires him to tamp everything down is beyond impressive — or from Schrader’s determination to keep making mature movies about adults, for adults. It’s simply that the sense of missed opportunity hovers over this like a hothouse mist. Considering how he respectively ties in climate change and the psychic toll of torture with spiritual matters in this loose trilogy’s other works, you can’t help but feel that this film’s headline-torn topics get reduced to toxic window dressing. They’re means to an end; and occasionally, the source of frustration with the movie as it toys with ideas it doesn’t fully connect to the character’s white-knuckle ride to redemption. You don’t need to know what exactly makes Narvel tick. You do need to know how these things feed into what the man behind the camera is trying to say with all of it, bigger picture-wise and character study-wise. Something vital’s been pruned away and punted to the periphery.

That the journey will end in a moment of violence, however, isn’t surprising — all ticking timebombs explode eventually, and Schrader consistently guides his pressurized protagonists to their necessary kabooms. What distinguishes Master Gardener from its brethren is that the violence is neither cathartic nor apocalyptic; there’s almost a perverse glee he’s taking in not serving a bloodlust for once, the better to shock viewers by his eventual endgame. This may be the first Schrader film that allows his signature God’s Lonely Man to experience a state of grace. Not even Adam got to re-enter the Garden of Eden after being expelled. The man at that desk at the beginning is allowed to step out of the room for once, and slow-dance in the dusky light. Even if the film fizzles, that’s explosive in and of itself.

Best of Rolling Stone