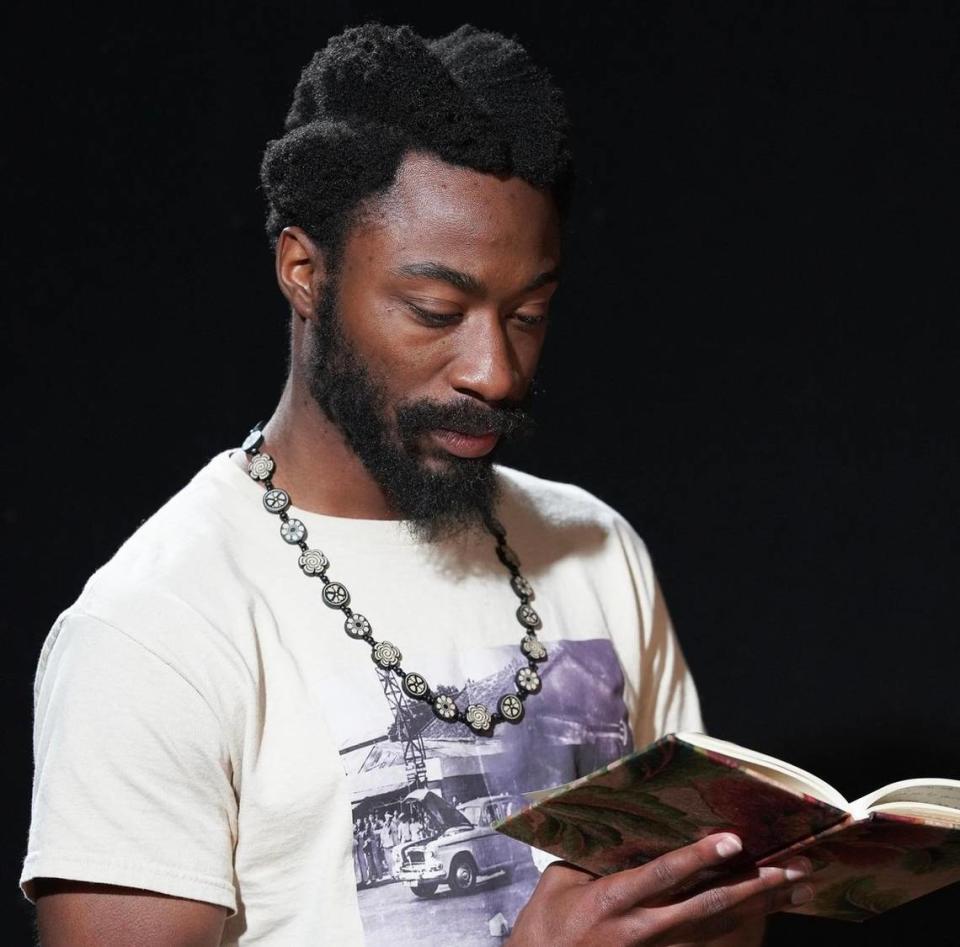

Marcus Lattimore passionate about new calling in life. It’s not football-related

It’s called “Popcorn Man.” And it’s risky.

It’s dicey because it’s different and, well, different isn’t always rewarded.

It is the story of Willie Earle, the black Greenville man arrested in 1947 for a crime he didn’t commit, snatched from his Pickens County jail cell and lynched by white men who were acquitted. “Popcorn Man” is that tale told from the voice of a hawker selling concessions at a lynching like he was working a baseball game, offering up popcorn and lemonade and peanuts to the crowds casually watching Earle’s blood drip — like it was the new attraction at the fair.

About 20 miles east of the courthouse where all those men got off scot-free, Marcus Lattimore became one the best high school football players in America, leading Byrnes High to three state titles as he galloped for more than 8,000 yards.

Lattimore, who later starred at the University of South Carolina, is now 32 years old, living in Portland, Oregon, with his wife enjoying days of outdoor walks and meditation and the new sport he’s excelling at: spoken word poetry. He practices and performs poetry almost daily, but he has found a calling by tapping into his thoughts and ideas and feelings and simply writing.

On the morning he wrote “Popcorn Man,” Lattimore was thinking of his grandfather, who was about Earle’s age and grew up just 10 miles apart.

Now it’s in the top tier of all his poems. At least among his top five, the quintet that he continuously reps and refines and has in his arsenal for competition. He can feel out the space, feel the environment and the vibe and know in his gut what poem the crowd needs to hear. Is it comedic relief? Is it something political that feels right? Or does he need to reach in his bag and pull out “Popcorn Man”?

“It’ll completely throw the judges in a tailspin,” he says of “Popcorn Man.”

Lattimore always goes with his best, but best can be different depending on what genre fits the moment. Luckily, his gut is usually right. Lattimore advanced through the winter qualifiers for spoken word poetry, topping the best poets in Portland week after week until he was named the 2024 grand slam champion of Oregon in March, earning him a spot in June’s BlackBerry Peach National Poetry Slam.

“I have a lot of responsibilities around the city right now promoting poetry and performing poetry,” he said. “I’m really in the thick of my season.”

On Monday, at a convention center 2,800 miles away from Portland, Lattimore will be honored for what he did in a past life. There to accept Lattimore’s South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame plaque will be his mother, stepfather and sister. Absent will be Lattimore.

For so many years, he made sacrifices that turned him into a football player worthy of all those awards and plaques. And, now, he’s making sacrifices for the chance to garner acclaim for Lattimore the poet, instead of No. 21.

Do they love Marcus or No. 21?

He’s adamant it’s not an exaggeration.

That night, color was gone. It was as though he was looking through a scuffed-up window pane, everything blurry and fuzzy. And he was looking out over the crowd in 2019 as someone read off his list of accomplishments before being inducted into the University of South Carolina’s Athletics Hall of Fame.

That he was this transformational figure in South Carolina athletics, the recruit who signed with Steve Spurrier and changed the Gamecocks’ football program. The freshman who rushed for nearly 1,200 yards and helped USC beat Alabama and Georgia. The guy who owns the rushing touchdown record despite suffering two season-ending injuries. The man who suffered one of the most gruesome injuries ever seen on television and was still drafted.

And the star universally beloved — so revered that children invited him to their birthday party and so kind that he’d actually show up. Even now, he admits, “I feel like I could burn down the city and people would still love me.”

But would they love Marcus or would they love No. 21? Because they don’t really know Marcus. Heck, Marcus didn’t know Marcus.

Which leads us to the night of the university’s Hall of Fame ceremony in 2019, when there should have been cheers and smiles and nostalgia, and instead there was only dread. Dread and shame. Because all these people were gathered to honor this man they pegged as a saint, the man who didn’t just run so well, but was the most upstanding citizen. And Lattimore had to hear that knowing the truth.

“At that time, I was confronting all of my past mistakes,” Lattimore said. “And I was confronting some of the things I’ve done to the opposite sex. I was confronting all of that at once. It was all crashing at once.”

Lattimore talks of his shadow. There was No. 21, the role model everyone saw. Then there was the man lurking in the darkness, the man with destructive habits, “from porn addiction to sex addiction to womanizing to manipulating,” he admitted.

That hall of fame reception was in October 2019. Four months later, Lattimore and his wife, Miranda, booked plane tickets to Portland and began selling off their possessions. The murder of George Floyd and the reception of the Black Lives Matter movement in South Carolina, Lattimore said, only furthered his conviction for a fresh start out west. He remembered his time with the San Francisco 49ers, being so far away from home and feeling free.

Four years later, he says this: “I love the state of South Carolina, I’m a proud South Carolinian. But if I would have stayed in that environment, I don’t know if I’d be here. Truly. Because it was so pressing. My wife and I, we knew. It was time for something new.”

Around that time of his move, Lattimore wrote a poem titled, “The Confrontation.” It starts like this:

“As my focus carousels from one pleasure to another.

I’m building up a tolerance that wouldn’t please my mother

or sister, who went through, a whole heap of trauma.

Thanking God that she ain’t someone’s baby mama.

But see that’s my problem, never looked in the mirror.

Never thought I had an issue until it became clearer.”

Blending his past life with his new one

Lattimore’s poetry from 2020 reads like therapy. They are some of his first poems and they are confessions of man getting years of secrets and burdens off his chest. Lattimore was writing daily — “Emotionally purging myself,” he says now.

From his 2020 poem, “Coals Glowing”:

“... There’s two of your kind.

The one that you show,

And the one that you hide

I’ve arrived,

At,

The point where I teach.

Truly,

I don’t mean to preach,

But we have to unleash,

That other. …”

Lattimore has tried actual therapy with a couch and a counselor. But he tried it in South Carolina, where everyone knows who he is and even the counselor, he said, made presumptions.

He wants to try it again. Likely in Portland, where some of the people know him as just a poet and others know him as the poet who used to play football.

His mornings, now, are therapy. Daily mediation and the typewriter close by, able to catch the thoughts that arise from his subconscious. It can be anything. Sometimes humorous. Sometimes dark. Sometimes politically charged. Sometimes “Popcorn Man.”

What rarely gets on paper is anything relating to the sport Lattimore is known for. Football is almost all but absent from his life. He no longer directly works with the Division III Lewis and Clark Football program, where he was a running backs coach and director of player development upon moving to Oregon, but he does still mentor a few players on the team.

Even on his Instagram, under his name is just one word: Writer. He has 128 photos on his feed. Not one includes pads or a pigskin or No. 21.

He once played football, but “it’s just not what I do today,” he said.

It is almost like he’s erasing part of himself, as if making no mention of No. 21 so folks can only speak about Marcus Lattimore: Writer. Asked if the massive omission to his online persona was intentional, he starts his thought, then pauses, then starts again.

“I mean, maybe … you know, maybe I’m still working out my relationship with football,” Lattimore said. “I don’t have a lot of poems about it because maybe I’m just not ready to explore that area of my life yet. I’m not trying to erase it from my identity — because I’m proud of everything that’s happened — but the time has not been right to write about it.”

It just hasn’t come naturally. Any time he’s even alluded to his football career or the injuries in the poems, Lattimore said, he’s forced it. Plenty of others have tried to craft the tale for him, about the kid invited to the university president’s house. The kid whose perfection was expected. Who was known by an entire state and nearly left that state for college. The kid laying on a football field with his leg turned the wrong way.

And, yet, right now it doesn’t seem pressing for Lattimore. Not for a month at least. Because on Sunday, Lattimore and one of his teammates in their poetry group, Slamlandia, need to spend an hour perfecting a group piece. Then on Tuesday, the four members of Slamlandia will get together will run through their poems, sharpening each other with radical honesty and immense respect.

A few days after Lattimore’s national competition, Slamlandia will be in the Bigfoot Poetry Festival in a competition with 44 other teams. Each squad has to perform three individual poems and one group piece in front of judges, and there’s still some fine-tuning to do.

“We want to win,” he said.

On Wednesday, the group reconvenes to help Lattimore work through his poems ahead of nationals. He’ll run through his five best then share some of his new work. Then Thursday is the big poetry night in Portland, when Lattimore will jump from open mic to open mic across town like he’s a New York comic, trying out the same material for new audiences.

And if the crowd is lucky and the vibe is right and Lattimore’s gut is telling him it’s OK to take the risk, he’ll open his mouth to allow his deep baritone vocals to bellow. And then he’ll holler.

“Popcorn. Get your Popcorn.”