How the Manson Family Murders Turned Into 50 Years of Pop Culture Fodder

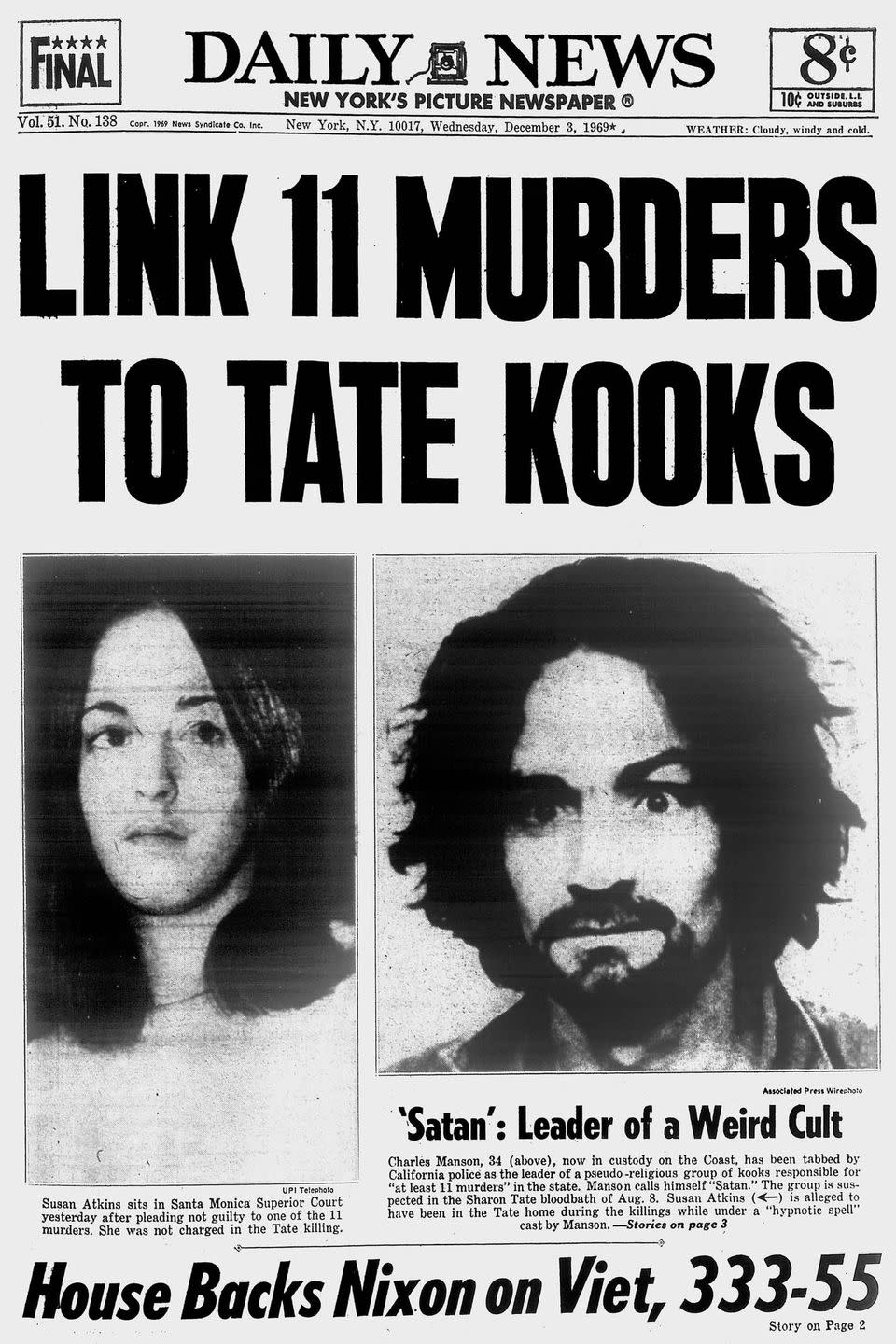

Charles Manson has become so much a part of our culture that it sometimes seems as if it were only yesterday when, just before midnight on Friday, August 8, 1969, in the chill glow of a waning crescent moon, four members of Manson’s “Family,” cloaked in black, sallied forth from the old Spahn movie ranch, northwest of Los Angeles, with instructions to “leave something witchy,” something dramatic, something awful that would burst the bubble that enclosed Hollywood’s cosseted celebrities, safe in their expensive homes in Bel Air, Malibu, and the environs. For reasons that remain obscure, Manson directed his followers to one of those homes, 10050 Cielo Drive, sitting by its lonesome at the end of a spidery road that wound through the upper reaches of Beverly Hills, between Benedict Canyon and Beverly Glen.

Manson was unacquainted with the occupants of the house, which had been rented by director Roman Polanski, then in London, and his wife, actress Sharon Tate, who was eight months pregnant. It was an unusually hot night, and she was lounging around with her guests—Polanski pal Wojciech Frykowski, coffee heiress Abigail Folger, and celebrity hairdresser Jay Sebring.

The witchy thing Manson’s proxies—Susan “Sadie” Atkins, Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, Linda Kasabian, and Charles “Tex” Watson—did on that fateful night was butcher everyone in sight, including a fifth victim, Steve Parent, who was in the wrong place at the wrong time, visiting the caretaker, a friend who in the evening’s one bit of good luck was left undisturbed in the property’s guest cottage.

These were no neat and tidy Mafia-style executions. Manson, thirty-four at the time of the murders, was partial to knives. Former Family member Dianne “Snake” Lake explained that Manson taught his groupies, “You stab and then you rip up, the reason being that you would hit as many vital organs as possible.” While Kasabian stood guard outside, the other three knifed the victims 102 times in total. There was blood all over, pooled on the floors, dripping down the walls, and splashed on the furniture. Tate alone was stabbed sixteen times, slashed twice, and hung by the neck from a rafter.

Atkins didn’t do herself any favors by later boasting that she had tasted Tate’s blood and confiding that had time allowed, she would have cut the baby out of her womb. She did, however, have time to write pig in large block letters on the front door with a towel soaked in Tate’s blood.

The next night, Manson again dispatched Watson, Krenwinkel, and Atkins, assisted by another Family member, Leslie Van Houten, on a second mission, this time driving them across town to Los Feliz and the home of Leno LaBianca, who owned a chain of grocery stores, and his wife, Rosemary. The Spanish-style house was quickly transformed into an abattoir. Leno was found with the word "war" carved into his stomach with a fork. The house was covered with bloody slogans, among them "healter skelter." (Spelling was never the girls’ strong suit.)

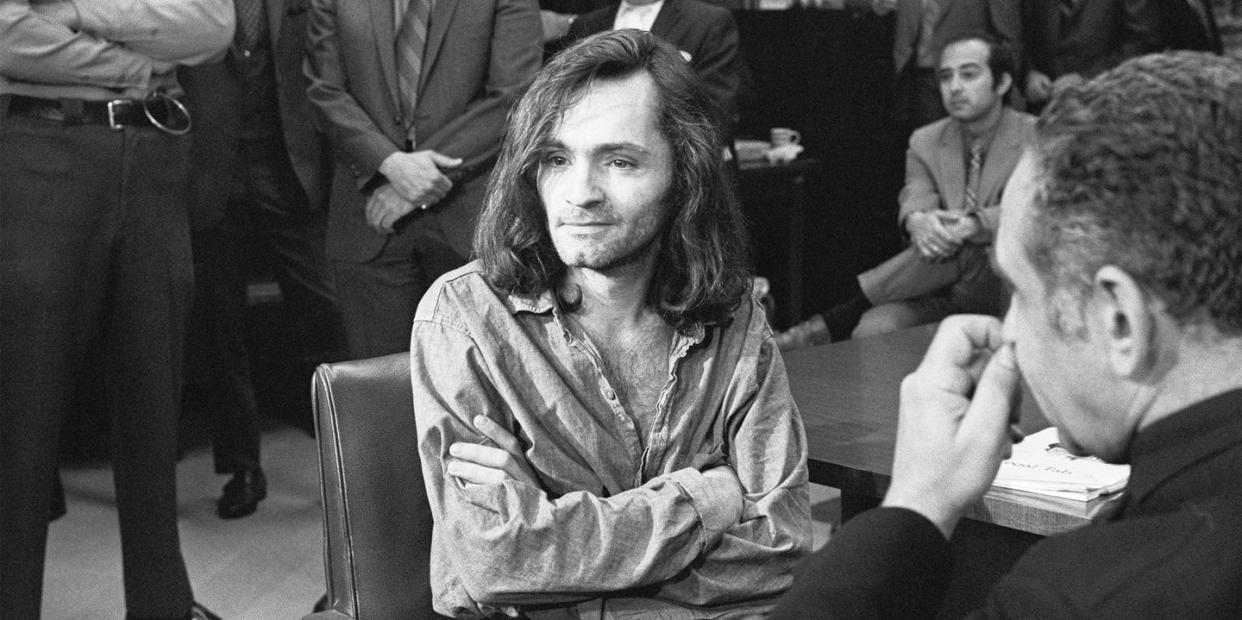

The butchery was bad enough, but the trial, which began in July 1970, was nearly as grotesque. The diminutive Svengali (Manson was five-two) daily demonstrated a bewildering hypnotic power over his Family, a spectacular basket of deplorables, estimated at one hundred, mostly girls, some not even out of high school. When he carved an X into his forehead, they carved X’s into theirs. When he shaved his head, they shaved theirs. All of them were defiant; none showed a shred of remorse. In addition to the three in the dock, others kept a vigil throughout the nine-month trial on the sidewalk near the Hall of Justice.

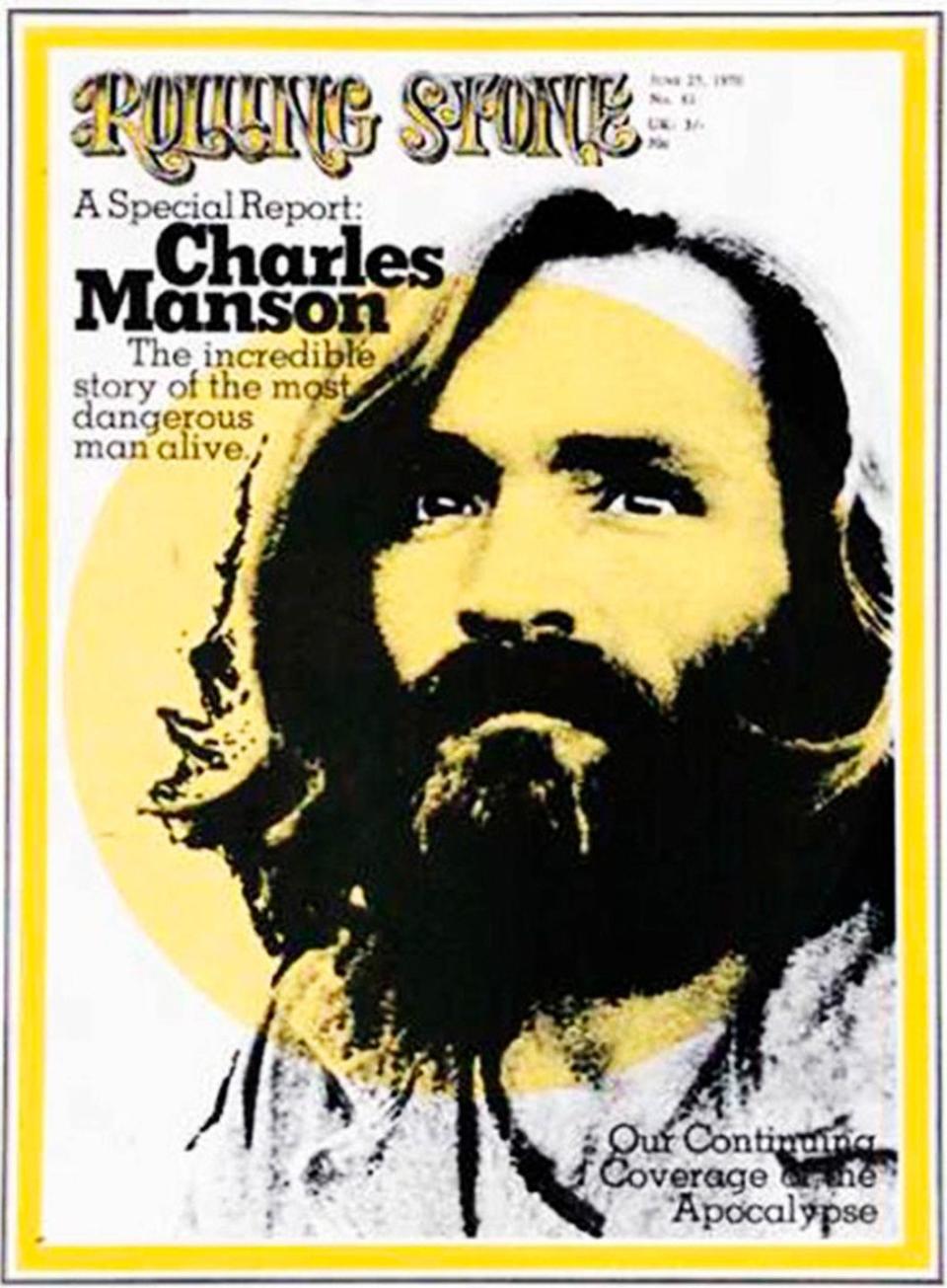

Manson did possess a certain charisma. Even the prosecutor who sent him away, Vincent Bugliosi, sensed it. He told Rolling Stone, “I couldn’t get someone to go to the local Dairy Queen and get me a milkshake, okay? . . . He had a quality about him that one thousandth of one percent of people have. An aura. ‘Vibes.’ ” Following their arrests, Manson and his followers had briefly become a counterculture cause célèbre, until evidence of their guilt became impossible to ignore. Joan Didion, who bought a dress at I. Magnin in Beverly Hills for Linda Kasabian to wear in court (she had agreed to testify against Manson in exchange for immunity), put a stamp on the circus by providing the most widely accepted interpretation of events: The Tate murders tolled RIP for the sixties. As she put it, “Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969.”

Manson had not been at Cielo Drive, and his active participation at the LaBianca home was limited to tying the couple up. Nevertheless, when the trial ended in April 1971, he, along with Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten, was sentenced to death, commuted to life with the possibility of parole when the California Supreme Court briefly abolished the death penalty the following year. Manson spent the next forty-six years bouncing around California’s prison system, including stays in San Quentin, Folsom, Vacaville, and Corcoran. He was denied parole twelve times. At his last hearing, in 2012, one of the parole- board members cited his comment to a prison psychologist: “I have put five people in the grave. I am a very dangerous man.”

Opaque as Manson’s motives appeared, later it became clear that there was a method, of sorts, to his madness. “Helter Skelter” referred to a tune from the Beatles’ White Album, which he regarded as a road map to an apocalyptic race war in which blacks would slaughter whites, and then turn to him in gratitude to run the world they had won, because they didn’t know how to do anything but kill whites and pick cotton.

The slaughter on Cielo Drive achieved at least part of its intended effect. The spookiness of it all—the grisly body carvings, the exorbitant number of stab wounds, the bloody, cryptic messages scrawled on walls and doors, in addition to the randomness of the killings, added to the apparent absence of motive—defied comprehension, raising the level of the crimes from slayings to atrocities that from the get-go created a miasma of fear.

“You couldn’t escape the murders,” recalls novelist and screenwriter Bret Easton Ellis, a Los Angeles native who was five years old when the Tate-LaBianca homicides occurred. He says that “the dread that infuses a lot of my fiction” stems in part from the killings. “People used to leave their doors unlocked, but the idea that someone could be roaming the canyons and just decide on your house—that kind of carnage haunted everybody there for decades.”

If Manson didn’t live to memorialize his golden anniversary, the rest of us have, thanks to a Manson-industrial complex that has been working overtime. He’s a gift that keeps on giving. In addition to comic books and multiple websites devoted to him and his groupies, jewelry, coffee mugs, and T-shirts displaying his image sell on eBay, Etsy, and Amazon. (One sports the slogan make murder great again.) When he died, he had 8,620 Twitter followers, to whom he tweeted messages like, “I am free, you are allin

jail, your minds are tarpped in your parents conditioning. Manson.” You can download his singing and talking ringtones to your cell phone—for free. Meanwhile, on MurderAuction.com, the starting bid in 2011 for a lock of Manson’s hair was $2,500. An X-ray of his spine was featured on Supernaught.com. The asking price? $8,500. His dentures? $50,000.

The biggest fish in the ocean of Manson books is Helter Skelter, Bugliosi’s blow-by-blow account of the investigation and trial, written with Curt Gentry; it is the best-selling true-crime book of all time, to the tune of seven million copies. The Manson shelf also includes two coloring books (one by “Venus Skelter”) as well as titles like At Home with the Charles Manson Girls and The Year of the Fork.

Given that the Cielo Drive murders took aim at the very heart of Hollywood, and the targets were either celebrities or celebrity adjacent, it’s not surprising that Manson and his followers continue, at a minimum, to play supporting roles in movies and TV series. One of the most successful was Aquarius (2015–16), an NBC procedural with David Duchovny playing a hard-boiled cop tracking a runaway who has joined the Family. Here, inverting Manson’s usual role as a countercultural bogeyman, he was portrayed as a bisexual right-wing hippie, tangentially connected to Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign through his lawyer, a closeted fundraiser.

Among the films, recent or upcoming, are Drew Goddard’s Bad Times at the El Royale, a Tarantino-lite neo-noir in which Chris Hemsworth (aka Thor) turns up halfway through as a Manson clone; Heiress, ’69, a short about Abigail Folger; The Haunting of Sharon Tate, with former Disney Channel star Hilary Duff; Charlie Says, which focuses on Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten in prison; and an announced biopic of Tate, coproduced by her sister, Debra, to star Kate Bosworth. Then, of course, there's Quentin Tarantino's, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which is one of the year's most anticipated films.

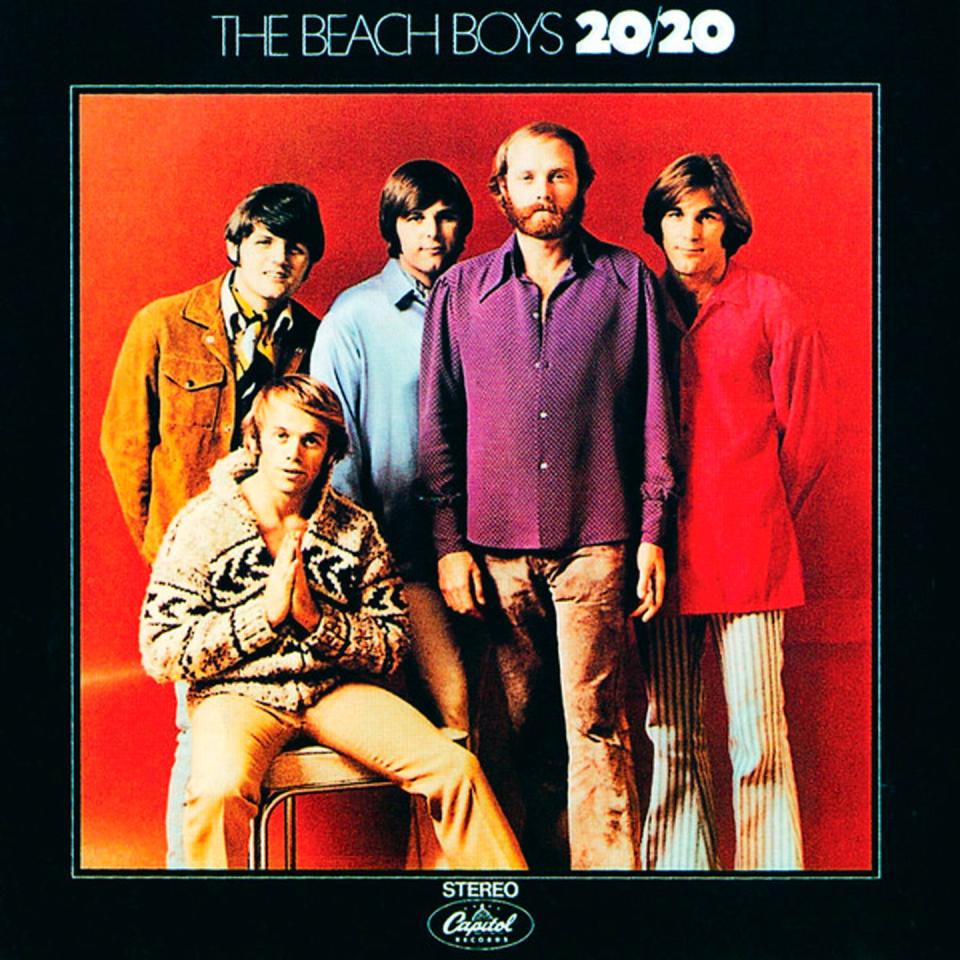

Baroque madness aside, Manson himself wasn’t that hard to parse. He had been in and out of juvenile facilities and prisons for most of his life, going to school on the pimps and grifters he met there. Charlie learned to strum a guitar from Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, head of the Ma Barker gang, while both were incarcerated in McNeil Island Penitentiary, in Washington, when Manson was a young man. He was released in 1967 and stumbled into California’s growing counterculture in Haight-Ashbury, where he repurposed himself as an aspiring rocker, and was just talented enough to penetrate the fringes of L. A.’s music scene when he later moved south. Neil Young compared him favorably to Bob Dylan. He befriended Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys and producer Terry Melcher (the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas), getting a taste of the wine, women, and weed that were rock-star perks. The Beach Boys even recorded one of Manson’s songs, but he was outraged that Wilson had rewritten and retitled it, and when his anger so spooked Wilson and Melcher that they cut him off, slamming the door on Manson’s dream, they and their kind became the enemy.

“For me, Manson was sort of a holiday from all the other maniacs,” says Joe Penhall, who has immersed himself in psychopathology as the creator of Mindhunter, a Netflix series that chronicles the origins of the FBI’s attempt to profile serial killers such as Richard Speck, who murdered eight student nurses in Chicago in 1966; the show will include Manson in its upcoming second season. (The Australian actor Damon Herriman is doing double duty, playing Manson for both Mindhunter and Tarantino.) “The thing about Manson was his mind,” Penhall continues. “If you’re him, you don’t get a girl in the back of a van by hitting her over the head. You get her in the back of a van by winning her trust. Manson’s creativity is focused on using people.”

To Penhall, Manson was (and is) a “totemic figure,” a lightning rod for a veritable tempest of social forces. He emerged at a time of cultural dislocation, when the bloodletting in Vietnam and new social freedoms had cracked the country along fault lines that were not only political but generational and racial—not unlike America today. As Manson himself once put it, “You know, a long time ago, being crazy meant something. Nowadays everybody’s crazy.”

In the words of director Mary Harron (American Psycho), whose Charlie Says will be released in May, “I think it is the girls that make that story stick.” Tex Watson’s contributions aside, Manson’s female followers took for themselves the historically masculine professions of serial and mass murder. For all that they were “lost” or damaged by broken homes and/or neglectful parents, as conventional wisdom has it, the three convicted with Manson came with all-American storybook backgrounds. Atkins was a former Girl Scout. Krenwinkel sang in church. Van Houten had been her high school’s homecoming princess. Says Harron, “The girls became predators, flower children gone crazy.” You could see them, if you wanted, as nightmare caricatures of hippie and straight cultures alike.

We do know that Manson flattered and battered his female followers, seduced, spurned, and seduced them again. Says Harron, “Women fall in love with terrible men, and will do stupid things for them.” Charlie Says shines a feminist light on this issue. According to its screenwriter, Guinevere Turner, “Nobody had asked, ‘What happened next?’ These women were stuck in solitary for seven fucking years. That was a new perspective. There was more story to tell. In the [current] climate, there’s a hunger to empower people who didn’t think they had a voice until now.”

The movie focuses on the work of Karlene Faith, a criminal-justice activist who regarded Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten as candidates for rehabilitation. She introduced them to basic feminist texts. According to Turner, “Karlene would say, ‘Here’s an idea . . .’ and they would say, ‘Charlie says . . .’ The thing was to get them to stop starting every sentence with ‘Charlie says’ and think for themselves.”

One thing Charlie liked to say was “Look straight at me and you see yourself.” Half a century later, Manson is the mirror from which we still seem unable to look away. But the reflections in Manson’s mirror aren’t only cultural or political. There’s also something creepy and intimate. Maybe one answer to the riddle of Manson and his girls is that they remind us of the ultimate unknowability of other people, even the seemingly unremarkable ones. Theirs is the story of Little Red Riding Hood in reverse: The smiling young girl at the door selling Girl Scout cookies is herself the Big Bad Wolf, and may be hiding a dagger under her cloak.

You Might Also Like