Maestro Leonard Bernstein had an affection for Detroit and Ann Arbor that lasted 5 decades

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

During one of several trips to Ann Arbor in the late 1980s to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic at Hill Auditorium, Leonard Bernstein wound up having lunch at the home of his personal assistant’s brother.

“My nephew, I think he was 3 or 4, he was backstage and he just said to Lenny, “Why don’t you come over for lunch?’” recalls Craig Urquhart, a University of Michigan alum who worked for Bernstein from 1985 until his death in 1990

"Lenny said to my sister-in-law, ‘Is that a real invitation?’ She said: ’Sure, it won’t be fancy. We’ll just get some sandwiches at Zingerman’s and come on over.’ And he said, ‘I’d love to!’ That’s the person he was.”

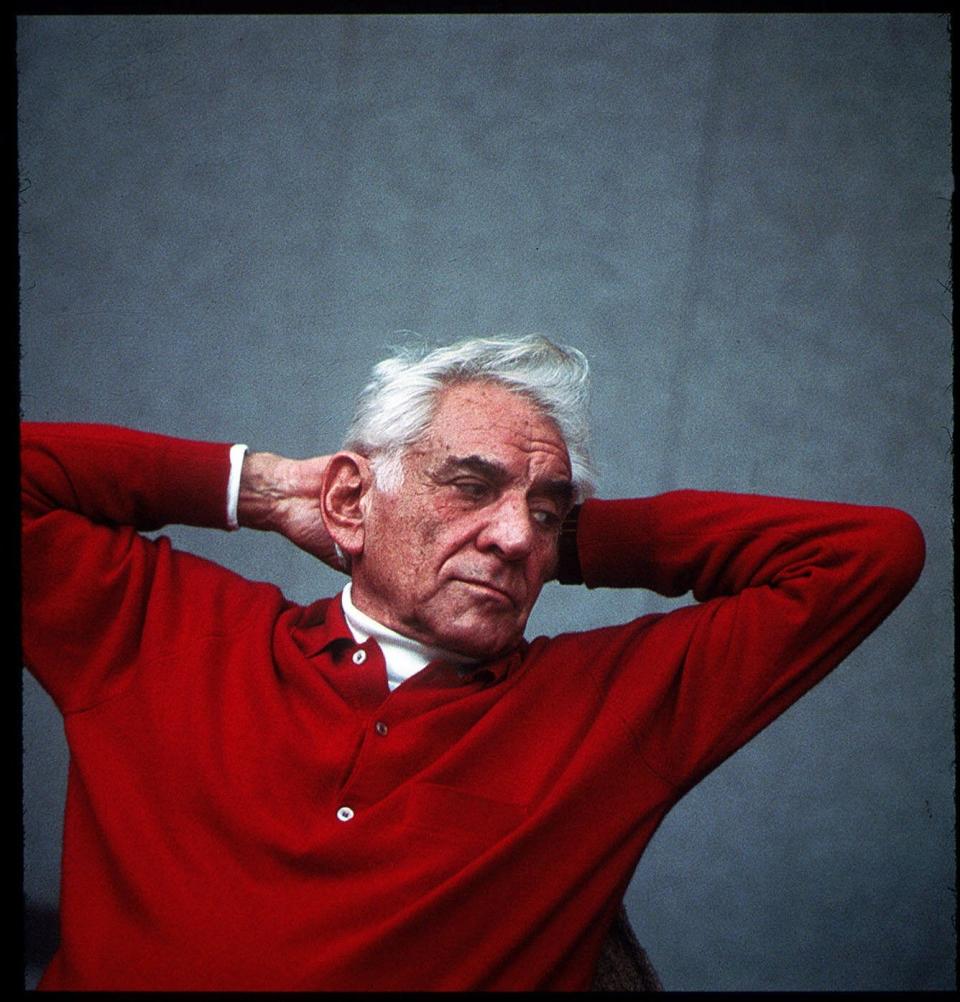

In his music and his life, Bernstein was one of the great cultural figures of the 20th century. A composer, conductor, educator, activist and humanitarian, he became an icon of classical music, conquered the Broadway stage with “West Side Story” and became a TV star with his “Young People’s Concerts” series for CBS. His awards ran the gamut from numerous honorary doctorates to Emmys, Grammys, Tonys and hit albums.

But Leonard Bernstein was also Lenny, the person who would stay an hour or more after performances to greet all of the fans who lined up to meet him. After his Hill Auditorium concerts, he would change out of his sweat-drenched shirt and hold court with his admirers in his dressing room.

“He just wore his bathrobe and had a whiskey and a cigarette and met people. That was his thing,” says Urquhart, who grew up in East Lansing and is a senior consultant to the New York City-based Leonard Bernstein Office, which promotes the maestro’s legacy.

Says Urquhart of the man behind the superstar: ”He was just a real mensch. He was a good guy.”

This weekend, “Maestro” opened at metro Detroit’s Maple Theater, Emagine Novi and MJR Troy and Ann Arbor’s State Theatre. Already considered an Oscar front runner, it premieres Dec. 20 on Netflix.

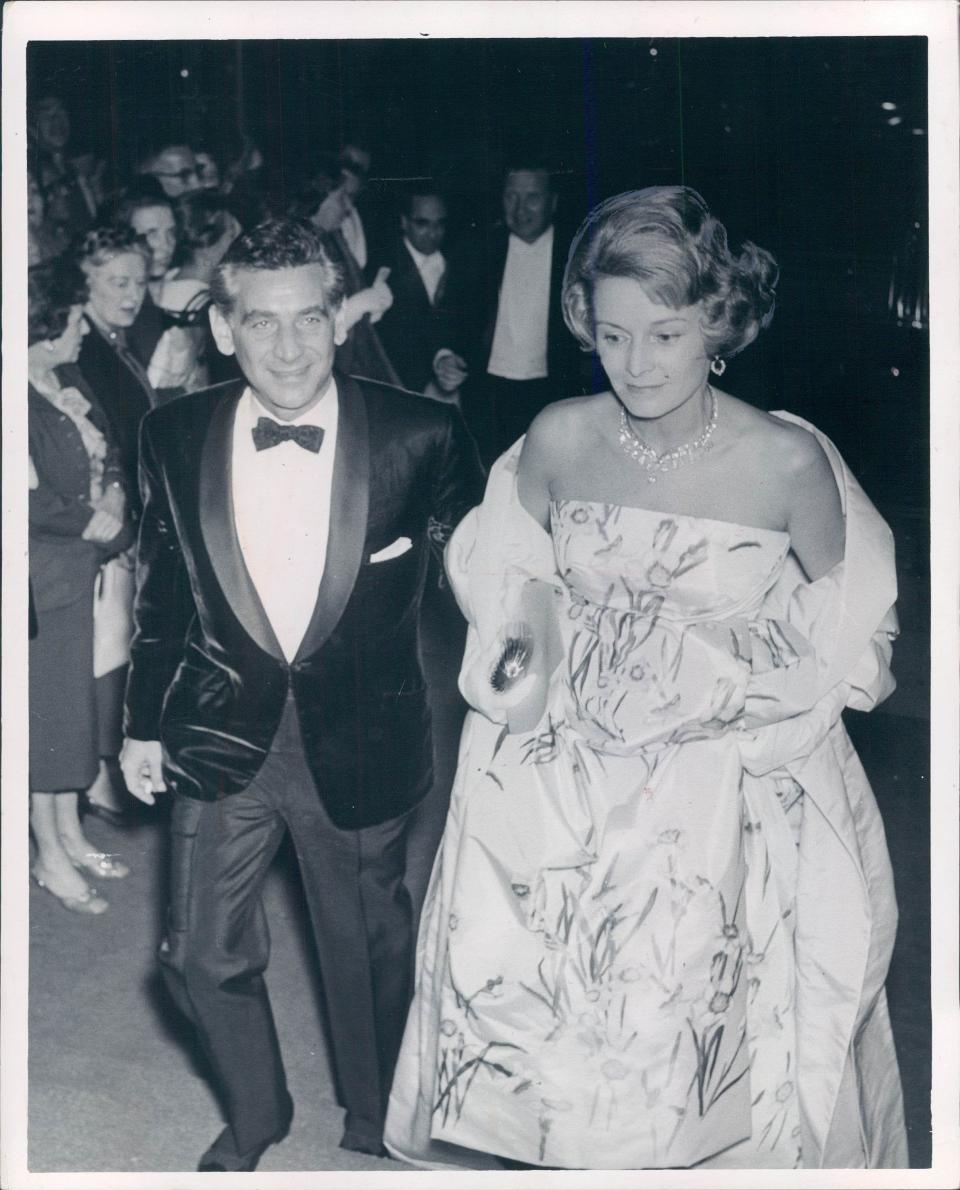

Starring, co-written, produced and directed by Bradley Cooper, the film is described on its official website as "a towering and fearless love story" about his complicated relationship with his wife, Felicia Montealegre, as well as "a love letter to life and art."

Bernstein may have belonged to the world, but he made time for Ann Arbor and Detroit during his 50 years in the spotlight, guest-conducting the Detroit Symphony Orchestra as a rising star and gracing the stage of the University of Michigan's Hill Auditorium in his twilight years.

The impact of Bernstein continues to be seen in today's musicians, notes the DSO’s current music director, Jader Bignamini, who just last weekend led a concert that featured soprano Meghan Picerno singing several Bernstein songs.

“Bernstein is such an inspiration for musicians of all generations, but I think that influencing the lives of countless young musicians is one of his greatest legacies,” said Bignamini via email. “While it’s impossible to describe his talents with a single definition, his intelligence, charm, wit and unimpeachable musical instincts brought people together. ... He mediated between different musical worlds — borrowing freely from contemporary styles like jazz, blues, and popular music — then shaped a ‘classical’ sound that became his signature.”

Bignamini counts Bernstein among his inspirations. “For many people, his writings and broadcasts opened the door to a lifelong love of music, and this is also why I like to talk with the audience at the top of my concerts here in Detroit.”

Bernstein wanted DSO job

The Motor City was among the starting points for Bernstein's brilliant career. In 1944, one year after he filled in for New York Philharmonic conductor Bruno Walter at Carnegie Hall and became an overnight sensation, Bernstein came to the Motor City three times to serve as guest conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. He returned six more times in the same role in 1945. All nine of those concerts were broadcast on WWJ-AM.

Bernstein also led the DSO once in 1946 and conducted the Detroit Little Symphony once in 1950. The latter group was created by DSO members in 1949 when financial troubles temporarily disbanded the full orchestra.

In a 1990 tribute to Bernstein's early Detroit ties by then-Free Press classical music critic John Guinn, former DSO principal trumpet player James Tamburini described going out for roast chicken with his old classmate from Philadelphia's Curtis Institute of Music.

Tamburini noted that Bernstein "wouldn't use any silverware. He'd just tear the chicken up and eat it. 'There's only one way to eat chicken,' he would say. 'You just tear it up.' He was a real ordinary guy — no pretense, no phoniness.”

Bernstein was interested in landing the job of DSO music director at that time, according to Tamburini. “He wanted this orchestra so bad. He said to me, 'What do I have to do to get this orchestra?' But they passed him up. After all, he was an American, and no one thought an American could be good enough to be music director of a major American orchestra in those days."

Indeed, when Bernstein was named music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1958, he became the first American-born music director of a major world orchestra, according to the Leonard Bernstein Office.

The same Free Press tribute described how Bernstein showed up in the late 1940s at the Ferndale home of DSO bassoon player Sol Lewis. Eager to hear a recording that Lewis had made of Bernstein conducting the DSO in his "Jeremiah" symphony, Bernstein was greeted by Lewis' daughter, Ann Weisman, then a teenager who had just had a fight with her boyfriend.

Weisman recounted how Bernstein cheered her up by playing the piano. “He played a piece called 'The Bicycle Song,' and he told me no one had ever heard it before. He said it was just for me.” Bernstein stayed until about 2 a.m. and smoked about 20 cigarettes during his visit. “I saved every one of those cigarette butts and put them under the glass on my dresser,” said Weisman.

Bernstein brought the New York Philharmonic to Detroit in 1960 and 1963 and to Ann Arbor’s Hill Auditorium in 1963 and 1967. In 1964, he also added an honorary doctorate from the University of Michigan to his growing list of accolades. Three years later, during his 1967 stop in Ann Arbor, he premiered “Inscape,” the final orchestral work of his longtime friend Aaron Copland (who’s played in the movie by Cooper’s longtime friend Brian Klugman).

Bernstein knew the importance of Midwestern universities with strong music programs and had good relationships with U-M and Indiana University that helped open doors for students. Melanie Helton, a former Indiana University student who now teaches at Michigan State University, was one of 25 students who toured in Israel in 1977 performing Bernstein’s works, including his operetta “Candide." He conducted it in Tel Aviv with the Israel Philharmonic.

“I just adored him,” says Helton, an accomplished soprano with a slew of international credits who is a professor of voice and director of the MSU Opera Theatre. Several years after being part of the Israel tour, she worked directly with Bernstein on creating the role of Dede in his sole full-length opera, 1983’s “A Quiet Place."

Helton remembers how Bernstein praised her for an impromptu change she made to the score while singing. “He said: ‘Do that again! Do that again!’ And then he actually wrote what I did (into) the music.” When it was time to do a workshop of the entire opera, the session took place at Bernstein’s New York City apartment in the Dakota. “Lauren Bacall was there, Yoko Ono was there, and Gilda Radner was there because they all lived in the Dakota,” she says of the “amazing experience.”

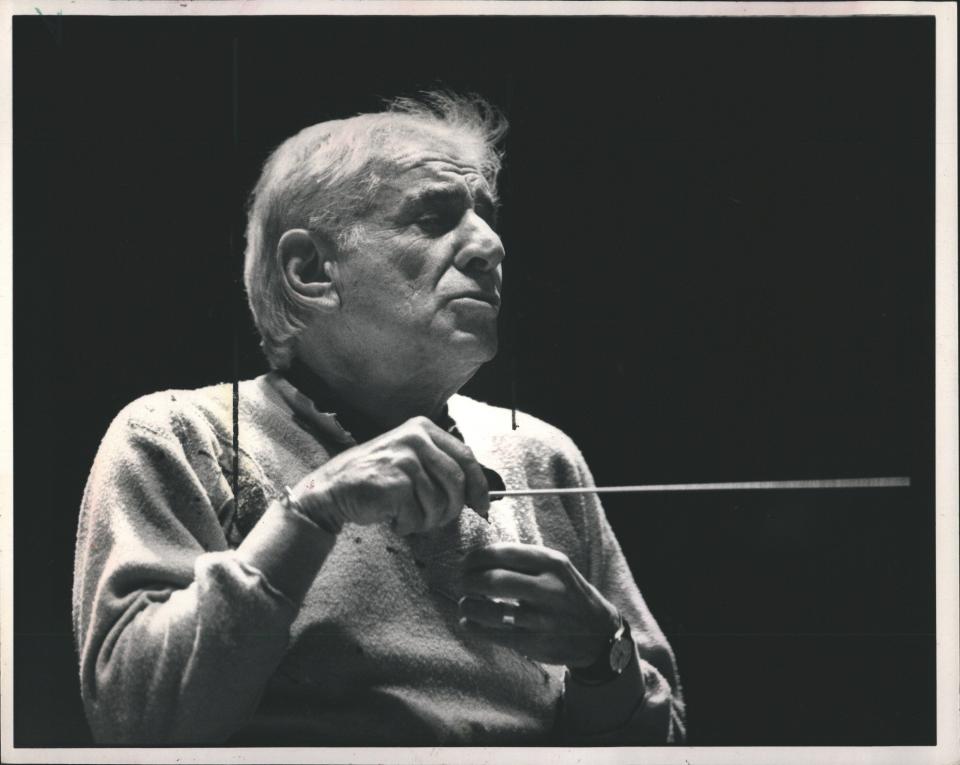

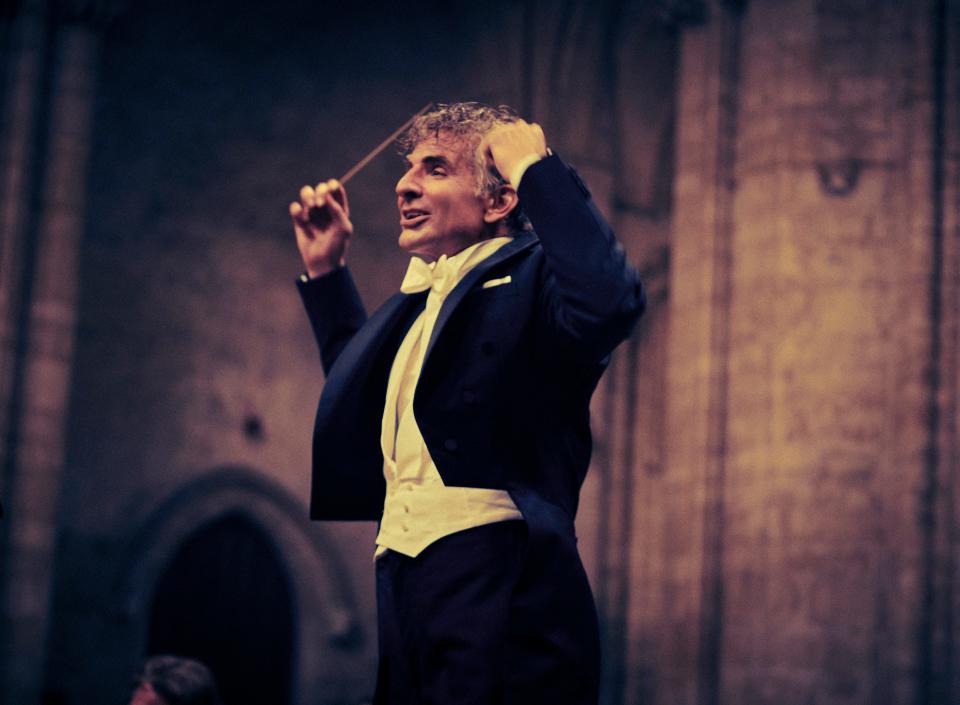

In 1984, Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic opened a three-week tour of eight American cities with two concerts in Ann Arbor, where he led the stellar orchestra for the 100th time in concert. As Free Press critic Guinn wrote then, even his rehearsals at Hill Auditorium were epic.

“All the Bernstein trademarks were in evidence: shifting his baton from one hand to another, the ecstasy on his face mirroring what was going on in the music; leaping into the air before a heavy downbeat and nodding affirmatively when a detail of the score was realized; blowing a kiss to the orchestra at the conclusion of a movement.” At one point, Bernstein was so caught up in the moment, he kicked a stool placed behind him off the stage.

When some U-M music school students walked to the stage to speak to him during a free moment, Bernstein “spoke to them with kindness and sincerity, making them seem, for the moment, the most important people in the world to him.”

Two years later, Bernstein led the New York Philharmonic at Meadow Brook Amphitheatre at Oakland University. More than 6,000 people filled the pavilion and lawn in 1986 to hear a program that included a dazzling version of Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” symphony.

At the reception afterward, Bernstein arrived late wearing a Detroit Tigers cap and a formal black cape. He told photographers with his usual gusto: “I'm sorry I'm late. But as Steve Martin would say, 'Well, excuuuuuuse me!'” Holding a cigarette and a glass of wine, he regaled some remaining guests with a story about beating the West German world handball champion in a game and also made a toast to the Motor City.

Bernstein's grand Michigan farewell

Bernstein’s swan songs to the state of Michigan were his final three concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic in Ann Arbor. There were two in 1987 and one in 1988 that celebrated both his 70th birthday and Hill Auditorium’s 75th anniversary.

U-M’s venerable president emeritus of the University Musical Society, Ken Fischer, had just been hired in 1987 to lead the group that still brings world-class music, dance and theater to U-M. Fischer's first concerts in his new role were the back-to-back Bernstein appearances, while his first big task was convincing Bernstein to put Ann Arbor on his limited 1988 tour.

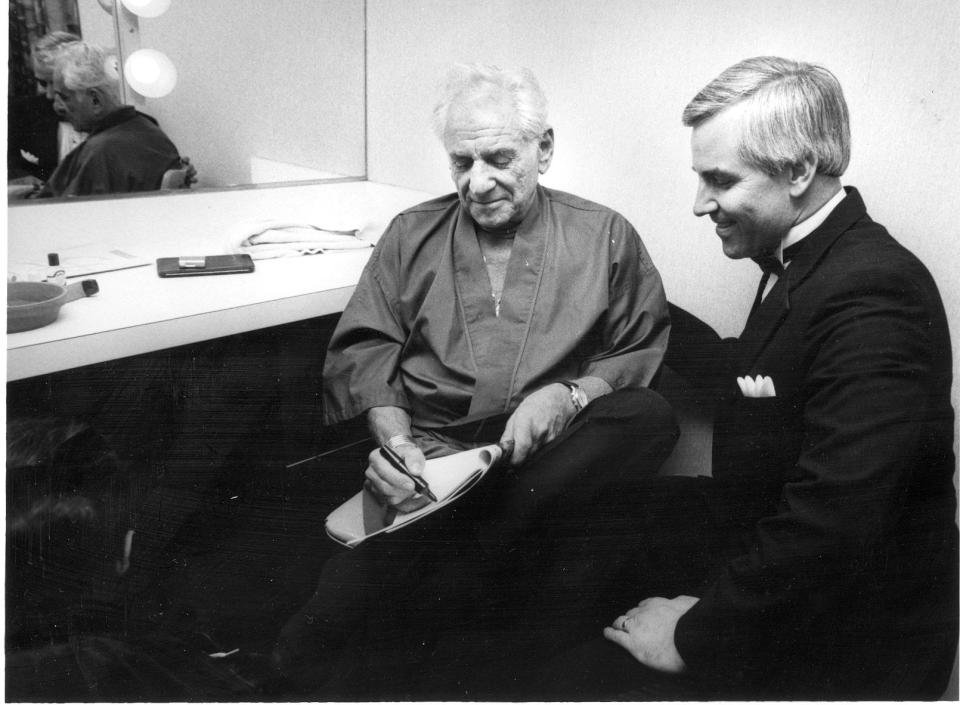

“I was 42 years old, totally intimidated, and my job was to invite Bernstein to come back the following year. … (As) this newbie, how do I invite him?,” says Fischer, whose 2020 memoir, "Everybody In, Nobody Out," chronicles his UMS tenure.

Using a strategy that a backstage photographer was able to document, Fischer got down on his knee in Bernstein's dressing room and looked the seated conductor in the eye to ask if he would include Ann Arbor on his 70th birthday tour. Recalls Fischer, “This is exactly what he said: ‘Ken I love this town, I love the people of this town, and I love this hall. We’ll be back.’”

That return trip in 1988, which featured music by Bernstein, Beethoven and Brahms, was an epic occasion and one of the highlights of Fischer’s 30-year tenure with UMS. Along with bolstering corporate support for UMS, the evening drew in young people in ways that honored Bernstein’s commitment to education.

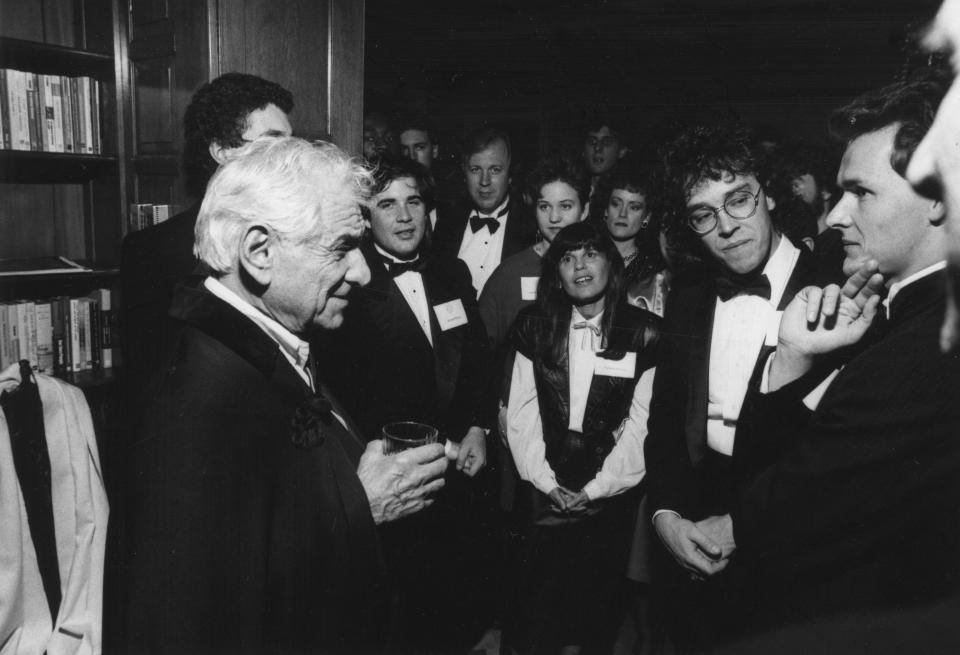

Some 550 tickets priced at $10 were reserved for students, who waited in line outside in chilly fall temperatures for up to 14 hours when they went on sale. Fischer’s idea of getting Bernstein’s next generation of fans to write him letters while in line — which he subsequently mailed to Bernstein’s representatives — helped convince the maestro to attend a post-concert reception at U-M President James Duderstadt’s official residence.

Major donors attended the reception. So did a number of students included on the guest list, a suggestion made by Duderstadt himself. Twenty spots on the guest list went to U-M music students, while another 10 went to the first student who waited in line for tickets.

Says Fischer, “Bernstein held court with these kids from midnight to 1:30. … At 1:30, I said to him, ‘Maybe it’s time to go.’ The president has been fading in the corner for a while. And I’d made arrangements with a bar on Main Street called Full Moon … (to) stay open so Bernstein would have a place to go.” Bernstein’s conversation with students picked up there and continued for several more hours.

For Sara Billman, vice president of marketing and communications at the University Musical Society, seeing Bernstein in concert in the late 1980s was a can’t-miss opportunity. Back then, she was a new U-M student with tickets to one of Bernstein's 1987 appearances. Then the music major found out that her oboe audition had landed her in a school band that would be rehearsing the night of the concert.

“I thought, 'Oh my gosh, I can’t give up tickets to hear Leonard Bernstein with the Vienna Philharmonic!'" she recalls. "I told the (band’s) conductor. …‘I’m so sorry, I bought these tickets and I didn’t know I was going to have rehearsal Monday nights, but I’m not going to be at the rehearsal next week.’ He said, ‘Well, you need to be!’ ... He kind of pushed back at me, and I was like, 'Forget it, I’m not going to pass this up.' So I skipped the band rehearsal. And at the end of the term, I got an A-minus instead of an A because that was the only rehearsal that I missed,” she says.

'Demanding but never cruel'

Can "Maestro" capture the charismatic genius for music that the real Bernstein had? MSU’s Helton can’t wait to see the movie and is impressed with what she has glimpsed so far of Cooper’s performance in previews. “The softness in his eyes is so familiar, the voice, the posture. It’s astonishing. … As somebody who was an actor for many, many years, it’s uncanny,” she says.

As Bernstein lives on through Cooper’s acting, he also continues to guide artists like Helton, who follows his example as a mentor in her classrooms. She says he was “very, very demanding but never cruel ... always kind” while working with her on “A Quiet Place.”

Says Helton, “When you did something he liked, he made a big deal out of it. And, of course, it made me feel like a million dollars. And I try to do that with my students.”

Contact Detroit Free Press pop culture critic Julie Hinds at jhinds@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Leonard Bernstein's affection for Michigan spanned 5 decades