‘Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger’ Review: Martin Scorsese Lends a Personal Perspective to an Engaging Testament of Movie Love

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

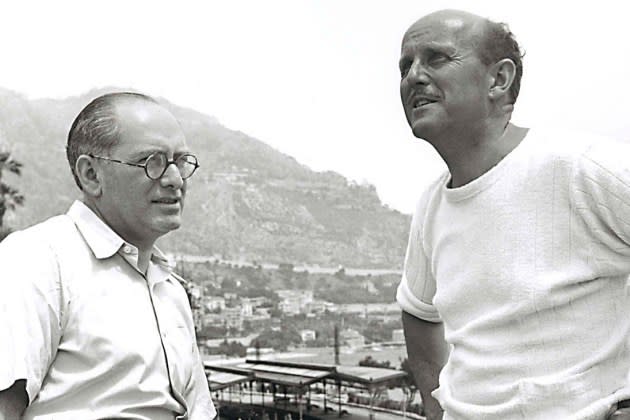

In the narrator’s seat for David Hinton’s eloquent documentary on the filmmaking duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, Martin Scorsese is the ultimate fan. Tracing his all-around movie obsession to his first viewing of the U.K.-based pair’s 1948 tour de force, The Red Shoes, he leads us through a dozen of their features and a few of Powell’s solo efforts, connecting key sequences to memorable scenes in his own work. But beyond its clear explication of the films’ imaginative and technical power, Made in England is also a testament to mentorship and friendship; Scorsese was close to Powell, who died in 1990, for the last decade and a half of the British director’s life, and Powell married Scorsese’s longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, in 1984.

The documentary ignites a longing to see the movies, whether for the first time or the umpteenth (many are available on The Criterion Channel). Hinton sets the story in motion with a few brief and trenchant elements of Scorsese’s early biography: the childhood asthma that kept him off the playground and led to lots of movie-watching on TV, particularly on that formative touchstone for New Yorkers of a certain age, The Million Dollar Movie, where he could enjoy repeat showings of such early Powell efforts as The Thief of Bagdad. He became fascinated with the movies of The Archers, as Powell and Pressburger called their production company. When he was an up-and-coming filmmaker, Scorsese recalls, The Archers’ unusual shared credit — “written, produced and directed by” — was an alluring mystery.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Using a straightforward chronology and unflashy but dynamic intercutting and split screens, Hinton deploys clips, stills, making-of footage and home movies, along with Scorsese’s single-location interview, to explore the filmmaking partnership. The Hungary-born Pressburger, who had fled the Nazis in Berlin and met Powell at a London story conference for a movie, impressed the Brit with the way he “stood the story on its head,” Powell recalls. The bond was instant and strong, and in excerpts from late-in-life interviews, their affection for each other is as evident as their intelligence and droll wit.

In their collaborations, Pressburger crafted the scripts, together they wrote the dialogue and produced, and Powell directed. The result was an especially influential run of features in the ’40s and early ’50s, movies with a bold sensibility and an emotional core that made an impression on Scorsese and his contemporaries in the New Hollywood, Coppola and De Palma among them. Lauding Powell and Pressburger’s ability to experiment within the system, Scorsese explains how The Red Shoes’ use of choreography and first-person perspective informed crucial sequences in Raging Bull and how its villain, the obsessed impresario Lermontov, is connected to the antihero Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver.

But while such features as 1947’s Black Narcissus and the following year’s The Red Shoes (“the ultimate subversive commercial movie,” per Scorsese) are well known for their hothouse intensity and embrace of artifice, it’s Scorsese’s deeply felt commentary on some of the less famous titles — The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, The Small Back Room — that are most striking.

Powell and Pressburger, like most filmmakers in the 1940s, were facing the propaganda machinery of World War II. Winston Churchill didn’t like the satire in Colonel Blimp, but they changed nothing to please him. When the film division of Britain’s Ministry of Information asked the partners to make a movie to help Anglo-American relations, they came up with the antiwar romantic fantasy A Matter of Life and Death, probably not what the bureaucrats had in mind. In 49th Parallel, they make a clear and urgent distinction between Nazis and Germans — the kind of nuance we could still bear to be reminded of.

In the postwar era of hard-bitten noir, they bucked the trend to focus on the idea of renewal. But as Made in America convincingly argues, there’s nothing Pollyannaish about this kind of optimism, and the psychology can be at least as troubled and complex as that of overtly darker fare. Their 1949 film The Small Back Room is intimate and bleak as its war-weary protagonist reaches for rebirth. (Sometimes called the less evocative Hour of Glory, the black-and-white film includes the astonishing sight, not excerpted in the documentary, of a fictional weapon test conducted amid the stones of Stonehenge.)

His friendship with Powell notwithstanding, Scorsese doesn’t sugarcoat the features that didn’t work for the filmmaking duo in their last years of partnership — “confused,” “conventional,” “uninspired” are some of the conclusions he draws. But he stands by Powell’s daring 1960 solo effort Peeping Tom, the story of a serial killer and a film that, Scorsese says, shows “how close moviemaking can come to madness.” Against his favorable assessment, Hinton has some fun throwing lines on the screen from horrified critics’ pearl-clutching reactions.

Scorsese also notes the intense sadness that pervades Peeping Tom. Emotion courses through all the movie love in Made in England. Scorsese’s personal connection to Powell began when he sought him out in Britain and found him living in obscurity and facing hard times. Recalling Powell’s mention in his autobiography of their first meeting, Scorsese’s voice grows just a bit thicker. The American auteur is still at the top of his game, but, at 81, he’s inevitably looking back as well as forward. Through a sharp lens and with deep feeling, Hinton’s film is a celebration of committing oneself to art, and the creative bonds that fuel the spark.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter