“I’m not going to say it’s a masterpiece, but it is a beautiful and a totally worthwhile entry in the Pink Floyd canon”: The highs and lows of Richard Wright’s limited solo work

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

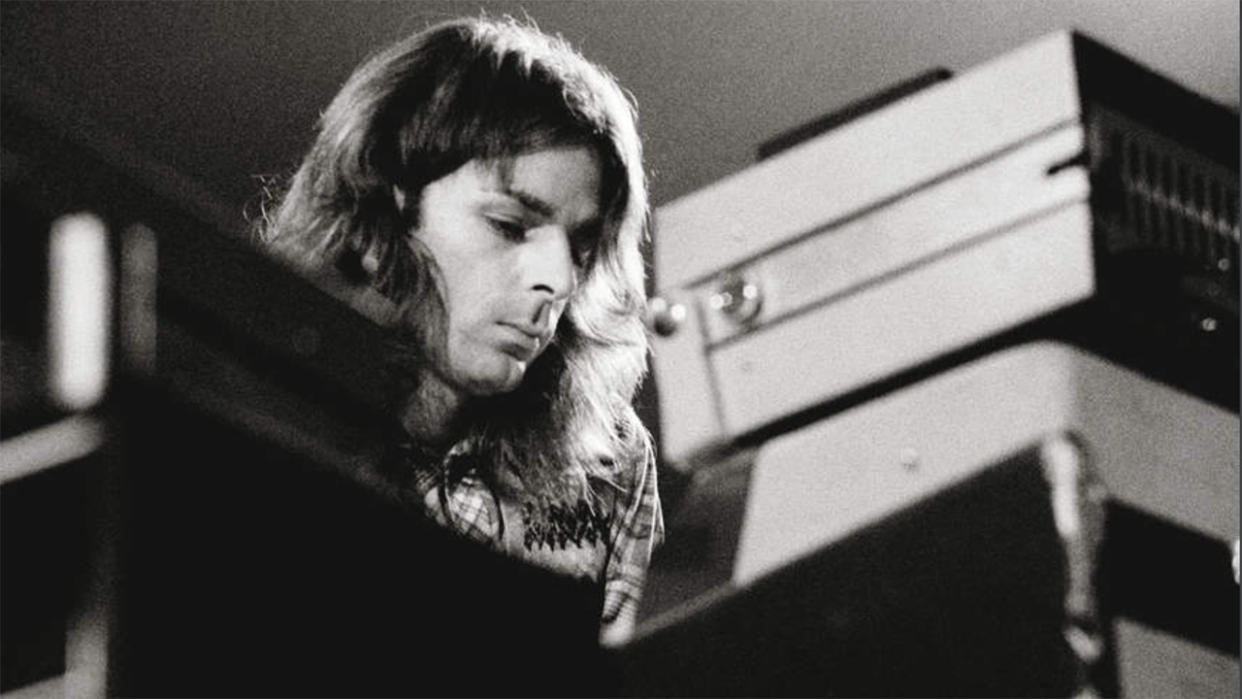

Pink Floyd co-founder Richard Wright redefined the idea of ‘the quiet one’ in rock. Discreet to the point at times of invisibility, Wright made other legendary taciturn group members such as John Entwistle or George Harrison seem positively garrulous in comparison.

Yet what he brought to Floyd was an unmistakable brilliance; his work was just there, shimmering and shifting, far less definable than the other parts of the sum. From the ethereal beeps and bleeps of the Syd Barrett days to his most magisterial mid-period material, to that beautiful bluesy improvisation around Old McDonald Had A Farm at the start of Sheep on Animals, Wright added considerable magic. Quietly. Texturally. So quietly, that few in the wider world had actually realised he’d left the group until his name was not on 1983’s The Final Cut.

Happier on his boat than in a recording studio, he was sacked from Pink Floyd by Roger Waters in 1979, but then returned famously to The Wall tour on wages, being the only band member to be paid.

Like that first last laugh, Wright rejoined the group as a session musician in 1987 before becoming a full member again for The Division Bell in 1994, and, after his sad passing in 2008, became – like Syd Barrett on Wish You Were Here – the main inspiration behind a Floyd album, The Endless River in 2014.

If it was difficult to see Richard Wright in Pink Floyd, one almost needs a microscope to assess his solo output: two solo albums and one collaboration were unobtrusively released in the 18 years between 1978 and 1996. An actual wet dream would stir more emotion than when Wet Dream, his first album (and recently re-released), appeared in September 1978.

Pink Floyd had been on sabbatical, having stopped working together in July the previous year, and although David Gilmour was the first to release his solo record, Wright’s was the first to be recorded. Of course, the first time solo Wright had been heard was on the 13-minute Sysyphus on 1969’s Ummagumma, something he had previously dismissed as “pretentious.” But now, nearly a decade later, times – and budgets – were different.

Although she was only eight at the time, Wright’s daughter Gala clearly remembers Wet Dream coming together. “We were around for the actual writing of it,” she says. “It was a unique situation, the kind of thing that one remembers in their childhood. We were living in Greece in this very basic house. There was electricity in there, so he had something plugged in.

“It happened quite quickly; it was a couple of months. We went back to school in the September of that year [1977] because we’d not been at school for a year, and then all the recording happened. I remember listening to it at boarding school on my Sony Walkman that I’d got for my birthday. I remember thinking Dad’s voice was really embarrassing. But then I loved a couple of tracks. I loved Cat Cruise right from the beginning.”

I’ve never been in control before, totally, so that’s one of the reasons I did a solo album, to put myself into that sort of situation. I wanted to see if I could cope with it. It was a challenge

Wright put a band together with Mel Collins on sax, Snowy White from the In The Flesh tour on guitar, and the rhythm section of Robin Trower drummer Reg Isidore and Gonzalez bassist Larry Steele. The album was recorded at Super Bear Studios on the Côte D’Azur between January and February 1978 – the studio that would soon be the base for Pink Floyd to make The Wall.

“On a solo project, you have to be on top of it, all the time, constantly,” Wright told Karl Dallas in 1978. “I’ve never been in control before, totally, so that’s one of the reasons I did a solo album, to put myself into that sort of situation. I wanted to see if I could cope with it. It was a challenge.”

With its mellow vibe, Wet Dream instantly dated on its release. “Among us younger fans, obviously, there was no way Wet Dream was going to make a dent at all,” Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets bassist Guy Pratt says. “It came out six weeks before [The Clash’s] Give ’Em Enough Rope!

“But it’s exactly what Rick wanted and there’s nothing wrong with that – just not then. If he’d put it out when, say, ambient house was just starting, everyone would have been all over it to do remixes, there would have been an Orb collaboration...”

“Wet Dream is an album that’s completely devoid of any punk aesthetic,” says Steven Wilson. “If you listen to Animals and The Wall, it’s there, which is why the Floyd were able to ride out the whole period in a way that a lot of bands of their generation probably weren’t. Listening now, with 45 years of hindsight, it’s really natural – a little naïve, but I embrace that as a positive now. I’m not going to say it’s a masterpiece, but it is a beautiful and a totally worthwhile entry in the Floyd canon.”

Wright later described Wet Dream as rather amateurish, but that is something Wilson refutes. “It doesn’t sound amateurish to me. A little gauche in places lyrically, perhaps, but Rick would not claim he was a lyric writer. His is almost an underachieving voice, which, in an age of Auto-Tune, I would rather listen to, speaking as someone who themselves has an underachieving voice. It sounds so natural.”

Any promotion there may have been for the record was curtailed because Pink Floyd had to go back to work, thanks to the looming inland revenue issues and the misinvestment of Norton Warburg. “Dad would go off sailing,” Gala says. “He certainly didn’t communicate with us anything about how things worked.”

“Pink Floyd were in terrible trouble,” Pratt says. “I mean rich people trouble. Not ‘They’re coming to cut the gas off, heat or eat’ trouble, but they had this massive tax bill; that’s why they were in France.”

After Wright’s well-documented ousting from Pink Floyd, his first appearance was in the unlikely duo of Zee with Dave Harris, who, as ‘Dee Harriss,’ had led Fashion on their second album, 1982’s Fabrique. The pair had been introduced by saxophonist Raf Baker Street Ravenscroft.

Their sole album, Identity, shouldn’t be overlooked, as it’s probably the most contemporary thing ever done by a member of Pink Floyd (bar possibly the New York no-wave free jazz of Nick Mason’s Fictitious Sports). For example, the track Strange Rhythm places itself somewhere near Donna Summer’s version of State Of Independence and All Night Long by Lionel Richie.

“Dave Harris asked us a couple of years ago if we wanted to re-release it. He’s such a lovely man,” Gala says. “We knew it wasn’t Dad’s proudest moment, but at the same time, we remember him recording the album well. “Dad loved sound. He’d really get into the weeds of how it sounded as well as being a sensitive musician. That’s what was happening with the Zee album – they were playing with the Fairlight, which was his new toy, really going for it.”

Identity seemed to be missing just that and, on its release in April 1984, the first commercial sighting of Wright in the 80s disappeared faster than Frankie could say ‘Relax’ (pop’s preoccupation at that time).

Wright’s final solo album, Broken China, landed in October 1996, by which time he had two further Floyd albums and tours under his belt. Co-written and produced with Anthony Moore, it was a grander work. “It has got a producer, which means it has an editor,” Pratt says.

“Broken China has a lot of the conceptual sweep that we associate with Floyd,” adds Wilson. “It sounds more like it was a part of what was going on in the 90s, a lot more use of digital technology. I love the fact it’s an epic.”

Rick got introduced every night. He’d never been introduced onstage in his life. It was so nice that he got to see the love people had for him

It also features two great performances from the late Sinéad O’Connor. However, in keeping with the rest of Wright’s solo work, and despite the elevation that The Division Bell offered him, it failed to make the UK or US charts.

In the early 21st century, Wright joined David Gilmour and Guy Pratt in the touring band for Gilmour’s On An Island. “That tour was such a great thing for Rick to end on,” Pratt notes. “That was about the love, and people will always talk about the version of Echoes on that tour.

“Rick was a sideman, so he got introduced every night. He’d never been introduced onstage in his life. It was so nice that he got to see the love people had for him.”

That, and his part in Pink Floyd’s Live 8 reunion in 2005, was the coda to his career. “It became more apparent as the years went on that David loved Rick so much,” says Pratt, “and kept him involved in everything, because he understood the value of their musical relationship. That was such a key part of Pink Floyd which gets overlooked in the ‘Alpha wars’.

“Rick went to Lindos [an island in Greece] first; David followed. Even when Rick was out of the band, David and he would meet up down there. David went to all three of Rick’s weddings; he was the only person who did.”

There would be no follow-up to Broken China as Wright died at home in London on September 15, 2008, aged 65. Rumours of a stockpile of solo material are, sadly, just rumours: “I’ve got a track that I worked on with Rick; I added drums and bass and it was really beautiful,” Pratt says.

“Unfortunately, it’s so many data storage formats ago, I can’t find it. I can’t remember what it was called because it would have had one of those silly, sketchy titles. If people are hoping for a long-lost album, I really don’t think it’s there.”

If anything, Wright’s real solo project was his sailing. “Someone said every band has a quiet one, but if Rick had been any quieter, you’d have to put out a missing persons alert,” says Pratt. “I sailed the Atlantic with him in 2002. There’s a picture of us in the Canary Islands before we set off. I looked at it the other day – that Rick, ‘Boat Rick’, so relaxed and confident. That was his happy place. It really got me, remembering that guy. That’s where he could be in control, running a boat.”

His other great pleasure was his grandchild, Gala and Guy’s son, Stanley, who was born in 2002. “He was a brilliant granddad,” Pratt says. “Totally naughty grandpa: he undermined all of your parenting, everything grandparents are supposed to do.”

Richard Wright once said that Pink Floyd was always a marriage that was on trial separation. Although, sadly he can never rejoin that union, while skirmishes continue in their current less-than-civil war, a corner of the group will forever be bathed in Wright’s warm, sun-kissed textures.

And for those who wish to explore further, there are these three solo works that go some way to fleshing out the body of this most hidden man.