‘Luke Cage’ Showrunner Cheo Hodari Coker on Embracing Exploitation

Leading up to the 20th anniversary of the March 10, 1997 premiere of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Yahoo TV is celebrating “Why Genre Shows Matter” and the history of how these shows have tackled universal themes (i.e. how much high school sucks) and broader social issues.

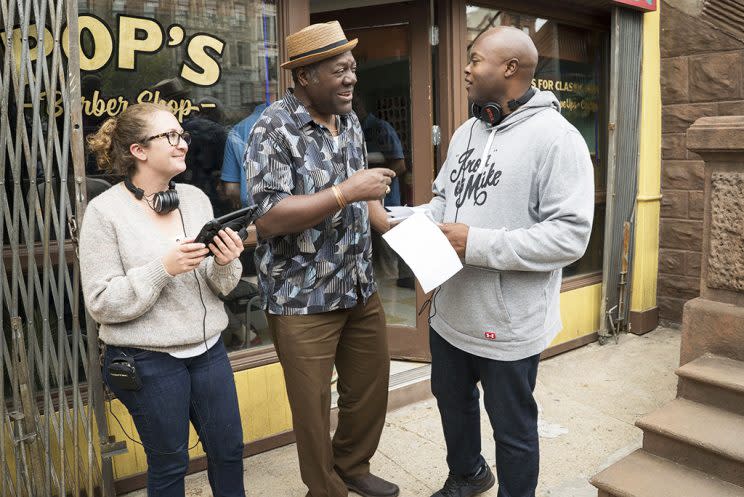

Showrunner Cheo Hodari Coker calls Luke Cage, “The Wu-Tangification of the Marvel Universe.” His early love of comics and later career as a music journalist dovetailed into the opportunity to bring one of the most iconic black superheroes to the small screen. He relished the chance to mine the exploitative roots of the character, while at the same time, using them to say something meaningful about today.

Related: 15 Genre Shows That Shaped TV Today

“Genre” — when used as an adjective, not a noun — was once simply code for adolescent swagger expressed as fantasy. Genre works that appealed on a visceral level were often scorned for their lack of intellectual depth. Eventually, nerddom — a culture traditionally associated with an overabundance of intellect and no swagger — intertwined itself with genre, and we arrived where we are today. “It’s just that every generation gets their turn,” Coker says.

He points to the wave of USC grads in the ’70s like George Lucas, Walter Murch, and John Milius who came up at the same time as Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola and brought with them an element of danger to filmmaking. “It was a combination of their independent film nerd sensibilities, once matched with big studio budgets, that helped Paramount and Universal and Fox just transform what we consider blockbuster films,” Coker says.

Then Oliver Stone and Spike Lee paved the way for “the second generation of geek: It’s the video store geeks. It’s everyone from [Quentin] Tarantino to Kevin Smith to Robert Rodriguez, Allison Anders, all these different people breaking rules all over again,” he says. “And now that next generation is out making television.”

This smartening up of genre has led to many interesting developments: among them, an increasing focus on diversity. Superheroes have long been used as metaphors to talk about social issues. “One of my favorite comic books of all-time is the graphic novel God Loves, Man Kills,” Coker says. He calls the book — from Chris Claremont’s influential run on The Uncanny X-Men — “probably one of my biggest influences as a writer in general, because it was really the first time I’d seen the power that a comic can have in addressing racism.”

One of the roots of racism is the lack of representation. After all, we fear what we don’t know and we don’t know what we can’t see. Comic book properties, in particular, have been slow to integrate: All 14 movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe to date have starred white men. We’re still four movies away from a black lead (Black Panther, slated for 2018) and seven away from the first female star (Captain Marvel, due out in 2019).

With Luke Cage, Coker shows us a broad spectrum of characters rarely seen anywhere in film or television. “I love the fact that we have two black male characters that you’ve never seen before. You’ve never seen a burly 240-lb. black man that can throw stuff that’s also a bookworm, and you’ve never seen a musician that’s a gangster. And the fact that you have a gangster that is really just a frustrated musician is interesting,” he says. “And what Simone Missick did with Misty Knight or what Alfre [Woodard] did incredibly with Black Mariah, I mean, it’s just next level.”

In many ways, Coker is reclaiming the vitality of the Blaxploitation movement of the ’70s — which is appropriate, since that’s what created the character of Luke Cage in the first place. “The Marvel office was near Times Square, so the writers would actually see the lines of people lined up on 42nd Street to see Shaft, Superfly, and everything else,” he says. Cage, in his mind, is basically bulletproof Shaft.

“All Blaxploitation is, is the opportunity for an African-American cast or lead actor or actress to do the same things that a white action hero gets to do,” he says. In many ways, Shaft was black James Bond. “The reason that Shaft has a dominant theme song,” Coker explains, “is because James Bond has a dominant theme song.” In fact, Shaft was written by the same man who wrote The French Connection, starring Gene Hackman, one of the seminal genre films of the ’70s.

“I wanted the show to not be embarrassed by the Blaxploitation roots, but embrace it,” he says. “Then at the same time, open up the camera, so to speak — widen the aperture — to include other genres. I mean, honestly, what Luke Cage is — it’s a hip-hop Western. And you have Luke Cage as the sheriff of Harlem. He’s basically Shane. He’s Shane or he’s any number of reluctant heroes as played by Clint Eastwood.”

Coker cites Eastwood’s Unforgiven as another major influence and expresses the power of genre (the adjective) through another Western classic, Tombstone. “I can’t remember who said it: ‘When given the opportunity to pick between the movie and the film, pick the movie. Because Wyatt Earp is a film — a beautiful film — if you look at what Lawrence Kasdan did with that. But Tombstone was the movie, and, ultimately, it’s the movie people keep coming back to.”

Meanwhile, genre creators are continuing to layer their work with more meaningful subtext than the surface trappings would lead you to believe. Coker has immense respect for Game of Thrones and frequently corresponds with showrunner David Benioff. “One of my favorite scenes is when [Tywin Lannister] is explaining why he did the Red Wedding and essentially what he’s saying is, ‘Is it better that I kill people at a dinner party, or do you want me to send everybody to war and risk our entire army?’ And yes, he’s talking about what’s happening in terms of that world, in terms of Westeros and all that stuff, but really, the metaphor is drone warfare. So the fact that you can have a fantasy show that at the same time is talking very topically about what has been happening in real world events — I mean, that’s amazing!”

Atlanta isn’t a genre show, but like Game of Thrones and Luke Cage, it uses familiar tropes to get at deeper truths. “It had to be driven by the plot, so it has to be the plight of a young man from Atlanta whose cousin becomes a rapper and he’s going to help him navigate the music industry. Sounds like Empire, right? But when you see Atlanta, it’s a meditation on all types of s–t,” Coker says. “Nothing to do with anything but an illumination on race and class that has never really been attempted as a television show, but really, is more akin to Ralph Ellison. The fact that you can do that is just the coolest thing ever. That’s what I love — I love a show that can basically subvert expectations and take you in directions that you never thought, and that’s what the best do. That’s what Atlanta does. That’s what Game of Thrones does.”

That’s what Luke Cage does. “It’s okay to embrace exploitative elements,” Choker says, “but do what you want in terms of exploring deeper themes when you feel the need to.”

Season 1 of Luke Cage is streaming on Netflix. Season 2 has been ordered.

Read more from Yahoo TV’s “Why Genre Shows Matter”:

Superheroes, Spells, and Sexual Abuse: A Conversation With Melissa Rosenberg and Sera Gamble, EPs of ‘Jessica Jones’ and ‘The Magicians’

‘Battlestar Galactica’ EP David Eick Revisits 5 Episodes That Remain Relevant

‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ 20th Anniversary: Joss Whedon Looks Back — And Forward