Loved 'Oppenheimer?' This film tells the shocking true story of a Soviet spy at Los Alamos

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

By now, we all know the name J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The so-called “father of the atomic bomb” has become something of a household name thanks to Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” (in theaters now), which depicts the creation of nuclear weapons that killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese citizens and ended World War II in 1945.

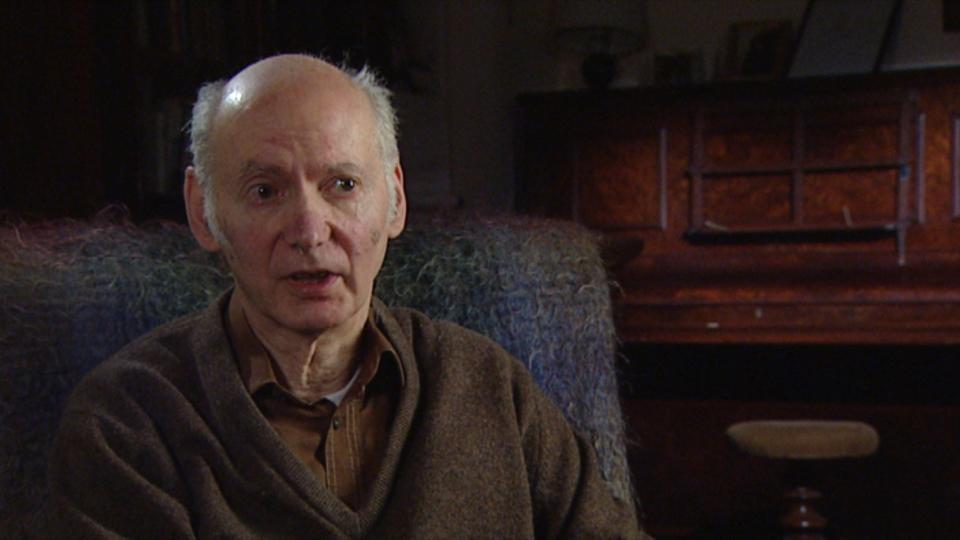

But the harrowing three-hour drama (and unlikely box-office sensation) only tells a piece of history. In the documentary “A Compassionate Spy” (in theaters and on-demand platforms Friday), director Steve James explores the jaw-dropping true story of Ted Hall, a bomb scientist who shared classified secrets with the Soviet Union.

Although Hall is not featured in Nolan’s movie, “I'm hoping people who see ‘Oppenheimer’ will want to understand more about what happened and turn to our film to get some answers,” James says. “They really are very good companion pieces.”

'Oppenheimer' review: Christopher Nolan's epic is a crafty blast of nuclear doomsday dread

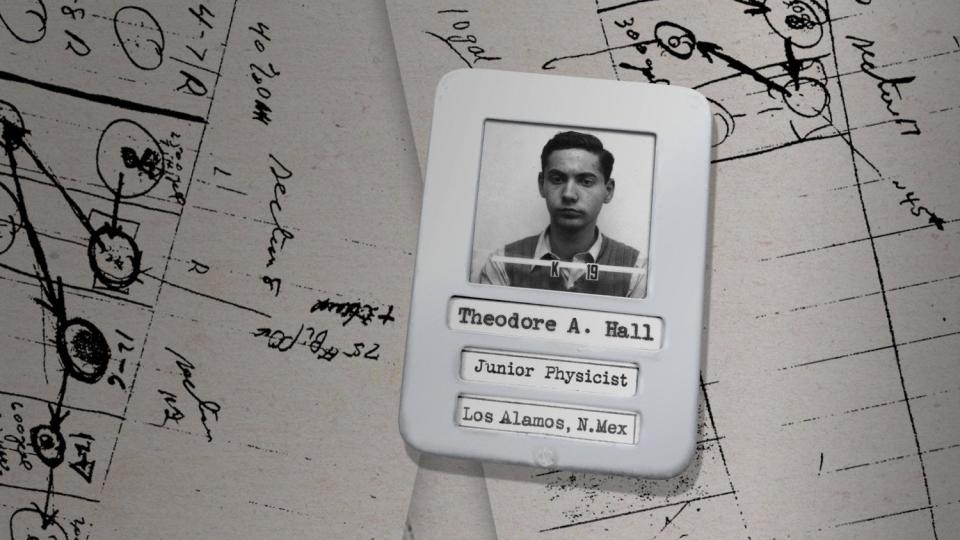

Who was scientist Theodore Hall?

At just 18, Theodore Hall (better known as Ted) was the youngest physicist recruited to work at the Los Alamos test site in New Mexico in 1943. Like his fellow scientists ‒ many of whom were also Jewish ‒ Hall was intensely motivated to beat Nazi Germany in the race to develop the first atomic bomb. But within a year, as it became clear that Germany was losing the war, he began to worry about the United States having a monopoly on nuclear weapons. And so, during a two-week leave to his hometown of New York, he shared a report with a Soviet journalist, detailing how the bomb worked, how far along it was, and a list of scientists working on the project.

“He didn't arrive at those fears from having privileged access to what was being discussed in the White House – he came to that conclusion because he was a savvy young man,” James says. “Whether you think his decision was wise or foolhardy, he made his decisions for the right reasons.”

Did Ted Hall work with J. Robert Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves at Los Alamos?

Hall was a key member of the team that built the implosion bomb. He likely had "very little interaction" with Oppenheimer and Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, who were busy overseeing the project, James says. But he probably worked with Klaus Fuchs, who unbeknownst to him, was also a Soviet spy. The Soviets employed multiple spies across divisions at Los Alamos, in order to ensure the intel they were getting was accurate.

“That’s how they both ended up sharing similar information: Ted was working on implosion and Klaus was head of that part of the program,” James says. “I'm sure they had interactions, even though neither of them knew what the other was doing in terms of spying.”

Who was Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs?

Hall was questioned by the FBI in 1951 about sharing secrets with the Soviets but was never charged due to a lack of evidence. Although Hall escaped prosecution, fellow spy Fuchs wasn't so lucky: The German-born British scientist was found guilty of espionage in the U.K., spending nearly 10 years in prison.

“They broke (Fuchs). They got him to confess he had done it,” James says. Meanwhile, “Ted had a steely resolve. He recognized that ‘OK, the FBI is really pushing me. They seem to know everything, but they're not arresting me.’ He wasn't going to cooperate in any way, shape, or form, and give them anything that could help them arrest him.”

Did Ted Hall help Julius and Ethel Rosenberg?

In 1953, U.S. Army engineer Julius Rosenberg and his wife, Ethel, were sent to the electric chair for supplying secrets to the Soviets ‒ the first Americans executed on such charges, and the first to be put to death during peacetime. Hall felt immense guilt that he had escaped prosecution, and considered confessing to the FBI in hopes of saving their lives.

Had Hall's wife, Joan, "not strongly discouraged him, he would have done it," James says. "She said to him, ‘You can't save them. You will only destroy us.’ And she was right about that. But the fact that Ted had that impulse does say something about (his character)."

Did Ted Hall have regrets about sharing nuclear secrets with the Soviets?

Later in life, Hall did express regret about supplying information to the Soviets, saying he was naive about leader Joseph Stalin's human rights atrocities at the time.

"Ultimately, he stood behind his actions, even though he came to have great misgivings about what the Soviet Union had become," James says. Hall placated his guilt with the knowledge that the Soviets would've found another spy.

"They had a number of brilliant scientists. They were going to get the bomb. The question was only when," James says. "It was Ted's actions – along with Klaus Fuchs and a few others – that in all likelihood helped them get it faster, and begin the Cold War and the arms race sooner. But it's not like we weren't bound for that outcome.”

How did Ted Hall die?

Hall died in 1999 at age 74. He suffered from Parkinson's disease and kidney cancer, the latter of which was likely caused, in part, by his work with plutonium at Los Alamos.

“A number of the scientists that worked (there) died of cancer,” James says. If he were to make this film again, “I would dig into that more and see if there was any way to conclusively prove that, in fact, the bomb took his life.”

'Oppenheimer': Christopher Nolan's new movie about nukes is 'the stuff of cinematic drama'

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Who was the Soviet spy in 'Oppenheimer' movie? Learn about Klaus Fuchs