We Love Lucy: How Nicole Kidman & Javier Bardem Became The Ricardos For Aaron Sorkin

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1952, the second season of CBS sitcom I Love Lucy set viewing records that, 70 years later, have yet to be beaten. The star was Lucille Ball, a lovable klutz from New York, and her husband Ricky was played by her real-life spouse—Cuban refugee Desi Arnaz. Together they founded Desilu Productions, soon to be the No. 1 independent TV company in America. In 1957, however, a scandal surfaced that threatened to tear it all down: Lucy was a registered Communist. Or was she? That fraught time is brought to life by Aaron Sorkin in his Amazon Studios release Being the Ricardos, starring Nicole Kidman as Lucy and Javier Bardem as Desi. Damon Wise sits down with all three to discuss the forgotten legacy of a most unlikely power couple.

Calling the Shots: Aaron Sorkin

Being the Ricardos is Aaron Sorkin’s 10th credited feature script and his third film as director. In that 30-year period—beginning with 1992’s A Few Good Men, which he penned for Rob Reiner—a lot has changed, and a lot has stayed the same. On a surface level, his work couldn’t be more diverse, covering American baseball (Moneyball), high-stakes poker (Molly’s Game), the battle for Afghanistan (Charlie Wilson’s War), and the ethics of Facebook (The Social Network). But, over time, recurrent themes began to occur: the business of politics, the politics of entertainment, and, perhaps best showcased in 2020’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, the importance of justice in a democratic society.

More from Deadline

On The BAFTA List, Good Films, But None About Topics That Worry Us Most

Javier Bardem Celebrates SAG Nomination; Dreams Of Riding Sandworm In 'Dune 2' This Summer

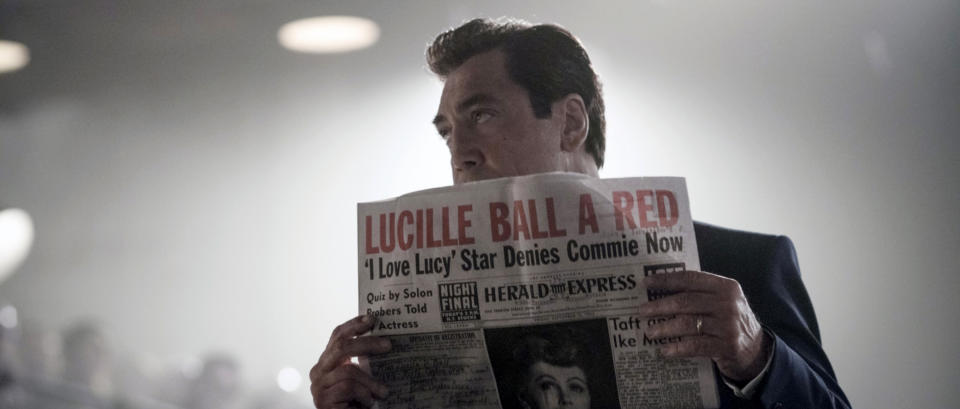

At the same time, Sorkin established himself as a powerhouse of American television, redefining the role of showrunner with his hit NBC White House drama The West Wing. Given all those credits, it initially seems strange to see Sorkin’s name attached to Being the Ricardos, which tells of a week in the life of Lucille Ball (Nicole Kidman) and Desi Arnaz (Javier Bardem) at the height of their sitcom fame in 1952. Their show, I Love Lucy, is the most popular in America, but Ball’s reign as a TV queen is threatened when a news headline surfaces—in lurid red print—accusing her of joining the Communist party in her teens. But soon you can see the appeal of the story, a confluence of many of Sorkin’s interests: TV, politics, entertainment, and power. “Yes, that’s fair,” he concedes, “but it’s really the backdrop against which a story about a famous marriage is told.”

Michael Buckner/Deadline

That said, Sorkin was not an easy catch. The film’s producer, Todd Black, started the courtship process in 2015, when he asked Sorkin if he was interested in writing a movie about the pair. “I was, but I didn’t know it yet,” Sorkin recalls dryly. “It would take me 18 months to get to yes. I wasn’t saying no, but I wasn’t saying yes either. He and I would meet once a month, or once every two months, and he’d kind of pepper me with more stuff. But what got me from the first meeting to the second meeting was when he said, ‘Did you know that Lucille Ball was accused of being a Communist?’ And I didn’t. The first thing I did was ask around because I thought maybe I’m the only one who doesn’t know that she was accused of being a Communist, and I wasn’t. Nobody knew that.”

Looking back, Sorkin still has no idea why Black, during that period of about 18 months, didn’t go to whoever was next on his list. “Maybe I was last on his list,” he says. “Maybe there was no one else to go to.” But something that happened toward the end of that year and a half sealed the deal. “I had lunch with a few people, one of whom was Lucie Arnaz, Lucy and Desi’s daughter. It was my first time meeting her. She was giving her blessing to this whole thing, and she leaned over to me and very quietly said, ‘My mother was not an easy woman. Take the gloves off.’ I thought, Great! Because the whole time I had been considering it, I was also considering the fact that the movie I want to write, her kids might not like. It turns out that’s the movie they wanted.”

Sorkin quickly decided on a structure, taking three important events from their lives, which actually happened over the course of about three years. “There was the accusation of being a Communist, which meant that I Love Lucy was almost canceled—that Lucille Ball herself was almost canceled; there was Lucy being pregnant, which the network didn’t like at all; and there was Desi showing up on the cover of a gossip tabloid with another woman, with the headline ‘Desi’s Wild Night Out’. I thought, If I make those things happen in the same production week of I Love Lucy, there would be an interesting structure that would suit my style.”

By using the filming of I Love Lucy—which Sorkin depicts as a series of power struggles on every conceivable level—he adds an extra, post-modern flourish. “People, or at least people in the U.S., have a very intense relationship with Lucille and Desi—or, really, with Lucy and Ricky Ricardo. When people picture Lucille Ball, they’re picturing Lucy Ricardo, just the way when people picture Charlie Chaplin, they’re really picturing the Little Tramp, and Charlie Chaplin isn’t anything like that. So, I thought it was interesting to contrast the real people and their lives with the comfort food of the Ricardos.”

To add another meta level, the film contains vox pops with I Love Lucy’s lead writers—but the parts are played by actors. “It turned out that there’s simply no one alive anymore from whom I could get firsthand research,” Sorkin says. “But those are all real anecdotes. What I did in those moments, seeing the older versions of the writers, was to make sure that there was nothing in the shot that could tell you what year it was when those ‘interviews’ were taking place. Because, in reality, if they were taking place today, those characters would be about 120 years old. But every story they tell is true. Everything that happens in the film happened, it just didn’t all happen in one week.”

Those oral histories were valuable, he says, “Because then you go to the dozen or so books that have been written about the two of them, and you find out that most of them aren’t very good because they were written for fans of I Love Lucy—there’s just not going to be any bad news in there.” There was, however, one, which is Desi’s own autobiography. “It’s called, simply, A Book by Desi Arnaz. He’s a fantastic storyteller. You’re reading it, and you can see the stiff drink that’s next to the typewriter while he’s writing. He has no problem taking you into darker places.”

It was in Arnaz’s book that Sorkin found what he was looking for: “A hairline fracture that would doom this marriage of two people in love with each other until the day they died, but who simply couldn’t make it work.” He cites the trauma of Arnaz’s teenage years in Cuba during the revolution of 1933, seeing his father go to prison, his family’s house burned down, and having to run away to a new country. “He came from a culture that has a very narrow definition of manhood, a culture in which manhood is incredibly important. So, as much as he admired, respected, protected, and promoted Lucy—because talent recognized talent—it was difficult for him to be second banana to a woman. To be second banana to his wife, well, it just wasn’t done.”

Desi, Sorkin says, “was as charming and charismatic as they come,” which is why he wanted Javier Bardem for the role. Surprisingly, the pair had only met once, for a brief moment, when Bardem handed him the Oscar for Best Screenplay for 2011’s The Social Network. “We made the movie, obviously, during Covid, so we Zoomed,” he says, “and right away, in the first minute, I knew he was right. He just is impossible not to love. He’s just so friendly, and gregarious, and funny. On top of that, obviously, he’s a world-class actor. I knew that those qualities that you can’t really fake, I knew those qualities were going to be so important for Desi in this film, because he was going to break our hearts at the end. We couldn’t be mad at him, we had to be sad for them.”

For Lucille, Sorkin wanted more than a straight impression. “We had to remember that we weren’t casting Lucy Ricardo, we were casting Lucille Ball, and that’s different,” he says. “Yes, there were going to be these quick shards of I Love Lucy in there, and she was going to have to have those skills, which Nicole does have. But more importantly, what we needed was a world-class dramatic actress with a dry sense of humor. A dry sense of humor and a good handle on language, who just owns the piece of ground she’s standing on. That was Nicole. So, when Nicole Kidman and Javier Bardem raise their hands and say they want to do your movie, your casting search is pretty much over.”

Like many of his generation, Sorkin, 60, first encountered I Love Lucy when he was a child, home sick from school. “They’d have four episodes on in a row in the morning,” he remembers. “It was fun to go back and revisit those. But what was more important than watching I Love Lucy, in terms of writing my script, was reading those scripts. Because I had to pick the episode that they would be doing this particular week. I chose ‘Fred and Ethel Fight’ because it presented, I thought, the best opportunities for Lucy to pound on the script. I needed to show the audience that she’s a comedic genius, that she’s the funniest person in the room, that she’s a comedy chessmaster who, whether it’s at the table read in rehearsal or being pitched in the writers’ room, she can, in her head, see what this is going to look like on Friday in front of a live audience. That, to me, was the reason to do the movie—because the real Lucille Ball is nothing like Lucy Ricardo. She doesn’t even sound like Lucy Ricardo, her voice is an octave below Lucy Ricardo’s. She’s a big smoker.”

Sorkin obviously knows a thing or two about the writers’ room, which is where we see Ball at her most cutting. “I invented those scenes, but it’s how it was,” he says. “I don’t think that there are a whole lot of people who could get away with that today, even the biggest stars. She or Desi ruled everything. And while Desi was a pat on the back—you got an amigo—guy, Lucy was withering. She could insult you and bleed you out quickly. You see it in the movie when she comes into the table read, the way she starts treating the director. She winds up this whole thing by saying, ‘I’m hazing you. It’s just my way of saying I have no confidence in you at all.’ That’s chilling. She would jump up and down on the writers, even though they were all close friends. On the crew, everybody.”

On the other hand, Being the Ricardos shows where that motivation came from. “She was paid a fortune to do exactly what she loved doing,” Sorkin says. “As she says in the movie, ‘All I have to do to keep this life is kill every week, for 36 weeks in a row, and then do it again next year.’ So, we see why she’s like that. What she doesn’t say in that speech, but what we see in other instances, is that the only reason she did this show in the first place was so that she could be with Desi, and that little postage stamp-sized living room set of the Ricardos was going to be their home, the place where they’re happy. If that goes away, either because she’s a Communist or because people stop loving Lucy, she loses her whole life. She loses everything.”

Sorkin doesn’t see much difference between TV then and now; the technology has improved but the mechanics are the same. “What’s changed the most is how television is consumed,” he says. “It’s pointed out, right at the beginning, that a big hit show today is 10 million viewers. I Love Lucy got 60 million viewers—at a time, by the way, when not everyone owned a television. And there would certainly not be more than one television in a house, so television shows were things that families watched together.”

To illustrate this, he tells the story of a woman who confronted I Love Lucy star William Frawley in a Los Angeles bar. “The woman said, ‘What are you doing here?’ Frawley didn’t know what she was talking about. She was confused, because she had just seen him last night in New York, where the Mertzes live, and here he was the next morning in California. He tried to explain to her, ‘No, we shoot the show here in LA,’ and the woman just couldn’t compute what ‘shoot the show’ even meant. She thought that for a half-hour a week, cameras were allowed into the home of the Ricardos and the Mertzes. Remember that in the early 1950s, television had only been around for a couple of years. It was consumed as an event thing, and many, many more millions of people watched it because there are so many more choices now.”

One major change is that sponsors don’t have quite the same clout these days. Sorkin doesn’t labor the parallels with today’s cancel culture (“I thought the similarities were obvious, so I shouldn’t point to them,” he says), but they are clearly there. “The sponsors certainly could have shut down I Love Lucy, just for showing Lucy Ricardo being pregnant on TV. On any other show, the sponsors could have gotten their way. But not that one, because of the power of Desi, the power of Lucy, and the power of ratings. In the case of I Love Lucy, the sponsors were Phillip Morris, who paid for the whole show; 60 million people a week. That’s a lot of eyeballs looking at your cigarettes. And, by the way, the characters back then smoked on television. Lucy Ricardo smoked and drank throughout her entire pregnancy. She smoked in every episode. I don’t think we knew back then that pregnant women shouldn’t smoke.”

Another way in which TV has evolved? “It was definitely the ugly stepchild of movies back then,” he says. “Which is something that only relatively recently has changed.”

Amazon Studios

The King of Conga: Javier Bardem

It’s hard to imagine an actor more rewarded or respected than Javier Bardem. At 52, his cabinet boasts an Oscar, a BAFTA, an Indie Spirit, six Goyas, a SAG award, a Golden Globe, and trophies from the Cannes and Venice film festivals. He’s worked right across the spectrum, making arthouse films with the likes of the Coen brothers, Terrence Malick and Darren Aronofsky, then pivoted to blockbusters such as the Bond movie Skyfall and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales with no apparent dent to his credibility.

It’s also hard to imagine an actor more humble. Though his casting in the role of Desi Arnaz in Being the Ricardos seems perfectly logical (to those with no objections to a Spaniard playing a Cuban), Bardem never took it for granted. “I was always asking my agent, ‘How’s that project going?’” he says. “And then I found out that Aaron Sorkin had started to write the script, which was even more exciting. I always knew that they were going to have other options for actors, and in the meantime, I was getting on with my life. I was working on other things, but I always had my eye on that project—like, how great would it be to play that role? Because I loved him as a character, as a person, for what he represented, for what he was and for what he became.”

Bardem’s own brush with TV stardom does not quite compare with Arnaz’s, as evidenced by a ropey Superman sketch that Jay Leno excavated in 2010. “When I was 19, I did a daily TV program called The Day Ahead, very early in the morning, for a year. It was a kind of variety program with news, interviews, comedy, everything. And around 8:30 in the morning I would do a sitcom—a six- or seven-minute sitcom about a family. A father, mother, grandmother and son. It was different from I Love Lucy because there was no rehearsal. We would do an episode per day, so we would have the lines the night before. Or even that same morning. On I Love Lucy, you had a whole week to rehearse.”

By contrast, nothing in Arnaz’s early life suggested that he was destined to become one of America’s most beloved television celebrities. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for the revolution in Cuba he might have stayed there, living a very comfortable upper-middle-class existence. Instead, he started his new life in America behind the counter at a branch of Woolworths in Miami, and by the 1950s, he had hit the big time: an actor, a bandleader, a producer with his own studio (Desilu), and married to the most famous woman on television, Lucille Ball. Others have made that journey from rags to riches, but few have done it so effortlessly, and this voracious drive is what intrigued Bardem.

“It’s all about energy,” he says. “It’s all about the vital energy that we all carry with us. Because, that defines us, in a way. If we’re in a room and somebody comes in, we feel their energy without even thinking about it. Is it a good vibe? A bad vibe? Are they boring? Are they fun? It’s more than an attitude because attitudes can change all through the day. He was relentless. He was always working, and if he wasn’t working, he was having fun. He was a very impressive person, who makes you wonder: how the hell does he do it? And that comes through the movie, I think. The energy is what attracted me the most because it’s an energy that I haven’t played that much, or that often.”

It’s also only Bardem’s second film with a strong musical theme: he was doing The Little Mermaid with Rob Marshall when the offer finally came. “Rob was the first person to trust me on that—ever—to sing, which is a brand-new thing for me, OK? And so, when the movie came along, I felt a little more confident, because I had done a lot of work for The Little Mermaid, and I knew, more or less, I could do it. That being said, the songs in the movie were not really my style. So, I was nervous. Insecure and very nervous.”

Bardem put in the hours with a singing coach because the musical numbers had to be recorded first. Then came the musical instruments—the guitar and the congas. “That’s something that I had to learn. I mean, the congas I could more or less do in sync with the drums because I can play drums. The guitar, I didn’t have any idea, and so I would have lessons—like everything else [during the pandemic]—by Zoom. Which is not the perfect way to learn anything, I think. Especially a musical instrument.”

Bardem’s love of music is well documented, and he’s amused by the story that he learned to speak English by listening to AC/DC. That said, he isn’t about to take his new skills to a karaoke night. “No, no, no,” he protests. “I’m actually very shy about that. I don’t know why, but I felt very exposed. It’s very intimidating to sing out loud in front of anyone. I don’t think I could do karaoke. I mean, I can have fun with that, but I’m not a guy who likes to sing. When I’m on my own, I might take a leap of faith and start singing some of the songs I like the most, by the hard rock groups I like.”

There was also a lot of work to do on Desi’s speaking voice. “I was trying to achieve a little bit of the high pitch that he had. I would say I was more obsessed with that than with the singing. Because the singing is very technical. When you’re singing, you have to be able to perform, and then you can go to different places, and react in different ways. But Desi’s speaking voice was a little bit higher than mine, and I was always trying to match that, knowing that I would never get there because we are so different.”

By the time shooting started, it had been nearly 20 years since Bardem had last seen Nicole Kidman, when she hosted a Hollywood screening of Alejandro Amenábar’s 2005 movie The Sea Inside, having starred in the director’s 2001 film The Others. “She was very nice and very helpful, and we ended up with the Oscar for Best Foreign Picture,” he says. “But that was it. And then we met for the shoot 16 years later.”

There was no time for rehearsal, just one preparatory Zoom call with Sorkin where they shared their fears and insecurities. “Because the movie really was put together very, very fast,” Bardem says. “Kudos to the production team, because it was in the middle of one of the peaks of the pandemic and everybody thought, ‘Wow, this is going to be so slow.’ But no, it was very quickly put together, and all of a sudden, we found ourselves creating these iconic characters with not so much time. Aaron was like, ‘OK. Don’t worry. I got your back.’ But the most important thing that he said to us was, ‘I don’t need an impersonation of anyone. That’s not what I’m looking for. We’re not doing I Love Lucy, we’re doing Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.’ That was a great relief because otherwise, I know that both of us were very obsessed with getting the external appearance right. I mean, it’s important but it’s not what matters.”

Bardem quickly settled into a groove with his acting partner. “She takes it seriously,” he says. “She works hard. She’s not lazy—she prepares herself very thoroughly. When you are working with her, she’s a great player. You throw the ball and she throws it back at you, and always with a sense of truth and depth. She doesn’t get stuck. She wants ideas. And that’s very important—especially on a project like this, where we barely had time to meet, let alone rehearse. We really learned about each other through the work. We met each other through Lucy and Desi. There was not much of Nicole and Javier there, in the sense that we didn’t have the time to sit down for three days and talk. We had a lot of lines to study, so there was not much time to do anything else other than work.

“She’s a great colleague,” he says. “I always felt supported by her and absolutely—what’s the word?—completed by her performance. Half of my Desi is her Lucy. And vice versa. That was something I felt in the first scene, and I guess she felt it as well.”

It’s a testament to Sorkin’s writing that Being the Ricardos gets to the essence of the Lucy-Desi love story through the inevitability of their breakup, which gives the film its sucker punch ending. “That was a tough scene to do,” Bardem says. “I mean, we did that scene on the third day of shooting. But we jumped into it, and it worked. The relationship doesn’t end there. It will continue, just as the show continues. But there is something broken, and I guess they love each other until the end of their days. And that had to be present. That had to be there. It had to be there in every scene. It’s not a relationship that you can just move on from. It was a relationship that will stay for the rest of your life. And that had to be implied in every scene, one way or the other, in every detail. In little details of how they approach each other, how they treat each other, how they relate to each other. So, it actually was very helpful to shoot that ending.”

An interesting facet of Desi Arnaz’s life is that he was a lifelong Republican (although Sorkin is quick to note that “he wouldn’t be today”). Given Bardem’s support for left-leaning causes in his homeland, it seems likely that this is a subject he would differ on. “I wouldn’t share [his politics],” he says, “but, for sure, I get it, given where he was coming from. His family had a long history of business ownership [in Cuba], his grandfather was the founder of the rum company Bacardi. So, they had lots of wealth, and then the revolution came, and he went to America. As the script says, he was more American than any other American. He loved America so much that he would do whatever it takes to be more American than anybody else. In that era, he was a big supporter of Nixon. It’s something I didn’t share with him, but it told me something about his way of thinking—his way of navigating through the politics of the time—and his own situation as an immigrant, dealing with American executives and bosses.”

Arnaz’s commitment to American values is reflected in the film, in his mortification when he learns of his wife’s fleeting involvement with Communism—and realizes that she might well be too stubborn to apologize. Though we know Lucy survived it, the looming threat of public opprobrium has new resonance today. “The canceling thing has been around for a little while under different names, Bardem says. “The witch hunt, you might call it. Also, in the Franco regime in Spain, there was a Communist hunt. And it’s scary because it’s about pointing fingers, and accusing people, and punishing them—and the law hasn’t had any say in it or taken any action about it. That’s scary because it’s a mob thing. It’s a mob movement that can create lots of pain and suffering. What is needed is real justice—not just to have an opinion about somebody’s guilt or innocence.”

Interestingly, he doesn’t quite see Lucy’s vindication—from J. Edgar Hoover, of all people—as a happy ending. “It’s sinister,” he says, “because the film is not about being Communist or not, it’s about being saved by the bell. It’s about nearly being destroyed by the machinery of lies and false accusations. When I read the script, I never felt like, ‘Oh, being Communist is a bad thing.’ Or, ‘Good Lord, she was a Communist.’ No, it’s about how Desi saves her neck from this battering. This battering built on lies and manipulations, bringing back stories from 30 years before. That’s what the movie is about, and that’s exactly what is going on today. The bottom line is: you’ve been accused—you’re done unless you prove your innocence. And that’s a dangerous thing.”

This isn’t exactly new in Bardem’s world, and it predates his acting career—before he was even born, in fact. In the ’50s, his filmmaker uncle Juan Antonio sat in a Spanish prison cell for mocking dictator General Franco’s government while his 1955 film Death of a Cyclist picked up the FIPRESCI Prize at Cannes. Has he developed a thick skin?

“Well, I’m nearly 53 years old. My skin is thicker in some places, in some ways it’s way thinner than it was when I was 20.” He laughs. “In terms of being outspoken, I share my views when I’m asked or when I think it’s proper to share them. Publicly or privately, that hasn’t changed. And of course, it brings consequences—especially if it’s a political opinion. In Spain, it’s been like that for a while, but it’s all around now.”

In that way, he feels he knows a little of what Desi and Lucy went through. “Not as hard as Desi and Lucy experienced it. Not as extreme of an experience. But my family has been always very [upfront], in terms of, for example, positioning ourselves against the extreme right-wing in Spain. What I’m saying is, you learn that once you have an opinion, you’re going to meet somebody that is opposed to that opinion. But does that mean that you have to cease to have any opinion about anything? You can keep it to yourself, but that’s saying you want to be liked by everyone, and that’s kind of utopian.”

Despite the pandemic, Bardem had a pretty busy 2021; aside from Being the Ricardos, he wrapped on The Little Mermaid and a lower-budget musical comedy for kids, Lyle, Lyle, Crocodile. Theoretically, there will be a Dune: Part Two, but apart from that, his slate is clear, although he’s still buoyed by the success of his recent Spanish film The Good Boss, a dark workplace satire about a ruthless manager. The film recently received 20 Goya nominations—a record number—and is still in cinemas even though it premiered back in September at the San Sebastian film festival.

“It was amazing to see the reactions and see how people react to the movie so unanimously,” he says. “They laughed and they get a punch in the stomach when it comes to understanding what they were laughing about. Because the social commentary is very deep, going parallel with the dark comedy. The reactions here in the States and in London has been very in tune with how the audiences in Spain had reacted, so, the movie translates very well. Because we all know about that kind of abuse of power. We know that kind of person. We’ve heard of him, we know of him, we’ve seen him, and sometimes we even have suffered him.”

Is it important for him to carry on making films in Spain as well as the U.S.? “Yeah. Of course. It’s my country, it’s my language, my place, but I never thought of making a plan about it. We’ll see what comes in, and if it’s good I will go there. Wherever it is, regardless of where the movie is being shot or where it’s being located. I don’t speak many languages, unfortunately. So far, I can do it in Spanish and English.”

With no plans to direct (“Maybe later, man. I don’t know, but that’s a lot of work”), and nothing really on the bucket list, Bardem is happy to freewheel into the future, just as he did into the present. “Yes, there are roles that you might want to play here or there,” he says, “but, really, I take it as it comes, and that has been always the case. I wasn’t expecting to do the roles that I did, so, why would I change that, no?”

There are some exceptions, though, and he’s drawn to larger-than-life historical figures, like the 16th-century Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés and Colombian cocaine baron Pablo Escobar. “I tried,” he shrugs. “I played Pablo Escobar [in 2017’s Loving Pablo], and I was about to do Cortés, but unfortunately that was canceled due to Covid, although it’s going to come back. So, yeah, there are some roles you might want to do, maybe because there’s something there that you are linked to, in some funny or interesting way. But mostly I’m just open to seeing what comes next.”

Amazon Studios

Playing Ball: Nicole Kidman

Nicole Kidman goes way back with Aaron Sorkin, to 1992 and his big breakthrough with the script for the military courtroom drama A Few Good Men, which starred her then-husband Tom Cruise. Their paths crossed again very soon after, on the 1993 medical thriller Malice, and after that, she mostly saw him on the awards circuit. “The Social Network, Steve Jobs, Molly’s Game…” She breathlessly reels off a list of his credits. “I’d just see his face, and I’d walk over and have a little chat to him. And that was that. I always wanted to come back into his life. I just didn’t know if it would ever happen.”

Some 30 years after that initial meeting, Kidman got her wish when Sorkin’s script for Being the Ricardos landed in her inbox. “I couldn’t put it down,” she recalls. “I just kept reading, page by page, because I was completely absorbed in the story, which was unbeknownst to me—pretty much everything in regards to her life. I knew the I Love Lucy show and Here’s Lucy, the follow-up, but that was sort of it. So, it was all an eye-opener for me, and I couldn’t put it down. I then Zoomed with Aaron, and we talked about the story and the magnitude of the role. He was like, ‘You can do it, Nicole—and I want you to do it.’ I was thrilled!” She laughs. “And then subsequently terrified.”

The legend of Lucille Ball is huge in America but doesn’t loom so large in Sydney, Australia, where Kidman grew up in the ’70s. Like Sorkin, she dipped into reruns on daytime TV while she was off sick from school. “I’d seen snippets, but I hadn’t absorbed the show,” she says. “I mean, I knew it, but I wasn’t obsessed with it, so going back to it was a huge discovery for me. She’s a miracle. When you go back and look at every single show, you see how good each show was. The woman was pure genius. She really was. And that’s not a word I just bandy around.”

To prepare, Kidman mostly watched the show for fun, but the really iconic sequences she watched over and over again, learning to mimic Lucy’s exquisite physical comedy. “I really became obsessed with her hands,” she says, “because her hands are very much a part of her. She had beautiful hands, beautiful nails, and she used them always to express herself and make points. I found incredible footage of her directing, where she’s on the set of the show, but she’s actually calling the shots saying, ‘Put the camera over here and do this and this.’” There was a lot to look at, “But because of the pandemic, I did have that wonderful thing: time.”

Still, as the start of production loomed, Kidman began to worry that she was running out of it. There was so much to look at, so many people to speak to. “And then, at one point, Aaron was like, ‘I want you to just leave the ghost of that and inhabit Lucy now from the position of who you are. Because a lot of these things you know. You intrinsically know many of the things that Lucy had to deal with. You know how to do this, Nicole.’” She laughs. “And he always wanted me to do it with swagger as well. He wanted sexuality. So, he would push me into not getting caught up in all of those details. I just had to go with what he was giving me and release myself into that. Respond to all the other actors, and the moments, and be alive in those moments.”

Studying I Love Lucy would obviously help in her portrayal of Lucy Ricardo, but what was the key to the real Lucy, Lucille Ball? “She’s human,” Kidman says. “She wasn’t going to be a stereotype or a caricature of what you’d expect. She was very human and fragile at times. Vulnerable. Direct. The smartest person in the room—that was a big part of it, her razor-sharp mind. And as I said, the hands. Just the way in which she would listen and then say, ‘No, this is how you should do it.’ She wasn’t afraid to say what she thought it should be, because the one thing she knew she had was talent.”

Lucy also had Desi Arnaz, played on screen by Bardem. Had she been looking forward to working with him? “Yeah,” she says. “Amongst actors, there’s not one person who doesn’t say, ‘I love Javier Bardem.’ I mean, the guy is the best of the best, and I never thought I’d get to act opposite him. It was intimidating, but it was inspiring, because, really, he’s fun and he’s really funny. He would dance before every take, because, obviously, music was so much a part of Desi’s life. We were very tactile, which was difficult because of Covid, even though we were tested all the time. But I would reach out and hold him, and touch him. And that was basically how we would start. We would start through touch, because we’re both intuitive and we work from feeling.”

According to Kidman, Ball had some pretty good moves of her own. “Lucy was a great dancer,” she says. “Oh my gosh, she was an amazing dancer. You see her in the films she made when she was starting out, when she was younger, and she’s a beautiful dancer. It’s why she has such command of her body. A lot of comedians have that dance quality to them, because when you’re a physical comedian, you’re using your body the same way as a dancer. At that time, you had to be able to dance, sing and act. You had to be a triple threat. You didn’t have a career if you couldn’t do them all.”

The touching, the dancing, was important to both Bardem and Kidman. “That marriage had chemistry,” she says, “so there had to be a chemical attraction between them. They were highly attracted to each other, which is fantastic for an actor because that’s so juxtaposed against the fast-talking, direct woman who’s leading the ship. She would then become, when she was with him, deeply emotional, fragile, and vulnerable at times. They would fight, but I think you see a lot of her desire to be loved. And she really loved him, and he really loved her. They had their flaws as a couple, but I really see that there was a great love there. Did it end the way you’d want a great love story to end? No!”

Surprisingly, Kidman doesn’t see anything especially tragic about their marriage breakdown. “They went off and married other people,” she says. “They went their separate ways, but they stayed in touch. So, it fell apart. But they also created a huge wealth of entertainment together, they had two children. So, they had a very, very fulfilling relationship. I think there’s almost an antiquated view of relationships where it’s like, you get married and then that’s it for your whole life, all the way through to the end. That’s a one-in-a-million kind of thing. And this over-a-decade relationship might have been very, very fraught, but it was also a very loving, very successful relationship.” She laughs, again. “I believe that. I want to believe that.”

Like Bardem and Sorkin, Kidman is on the same page when it comes to Desi, and the aching impossibility of their relationship. “He couldn’t be what she wanted him to be, ultimately. He could do many things for her, but there was one thing he couldn’t do, which was stay at home. He couldn’t be faithful to her, and he tried, I think. It’s complicated. She wanted the white picket fence and the man that sat at home, but she also wanted a huge career. And the one thing he could definitely do was protect her in business. He could protect her the best he could on the set. He could give her the confidence that she was the most magnetic, gorgeous woman in the world and the belief that she should have everything she wanted. But the one thing he couldn’t do was give her the home, give her what she saw as the complete picture, you know? And that was the end. She wasn’t willing to compromise on that. It wasn’t enough for her.”

Kidman talks a lot about Lucille Ball’s romantic side, but she says much less about the difficult woman described by her daughter, and wasn’t about to “take the gloves off” in her performance. “For me, that’s for Aaron as a director and a writer. He’s the dramaturg here. I’m the person embodying her. All I wanted to do—and all he said to do—was show that this was a living, breathing woman. This isn’t a cardboard cut-out, this isn’t a caricature and it isn’t a skit. She’s a living, breathing human being, and the humanness of the film is what I respond to. That’s actually the thing that I find gives you a film, and that’s what Aaron comes with. He comes in going, ‘I create drama. How do I do it?’ It’s all well and good to do a documentary or a wonderful biopic of these people, but, as Aaron says, ‘I don’t know how to write a biopic,’ which I think is fabulous.”

Something else that Sorkin comes with is nuance, which is especially relevant to the ticking timebomb in the story: did Ball really mean to tick the box and join the Communist party or was it just a slip of the pen? “I have to say, I love the nuance of that story,” she says. “Because the nuance of that story is, yes, she did tick the box, and she ticked the box for a reason—because of her grandfather. She ticked that box because that’s what he believed in. She was raised by him, and it was her way of saying thank you to him. She felt it was a betrayal, then, to do him in, because she loved him. That’s called nuance. That’s called reading between the lines. There’s information there that needs to be digested here so you can then understand a person, and I think Aaron’s a huge believer in that. I’m a huge believer. I mean, I know all of us probably are very huge believers, ultimately, in the need for the nuance. Particularly now.”

Inevitably, this, again, leads to a discussion of cancel culture. “It’s the strangest thing, but a lot of the people around me that have seen it, who are younger than me, they go, ‘Oh, it’s so relevant. It’s not a period film.’ And I’m like, ‘Why do you say that?’ And they go, ‘Because of cancel culture, because of gender equality, because of all the things that are in it—they’re not from the ’50s. Every single thing, we can all relate to now.’ I love that. Which is why I think Lucy right now is so inspiring. Lucille Ball is inspiring to a lot of people, and particularly young women, because she did it. She did it against all odds—even when she got divorced from Desi. Her daughter told me that she didn’t want to be a businesswoman. She loved the creative aspect of it. The business side of it was not her passion. But when she got divorced, she had to learn how to be a businesswoman. And she had to learn how to take care of herself and negotiate and all of those things. Because Desi had done that. So, now she had to learn it. And she did.”

At this point, the comparisons come creeping in. Kidman has also gone into production, founding her own company, Blossom Films, in 2010. Does she see anything of herself in Lucy’s story? “Well, I’ve had a lot of ups and downs in my career, you know? And so, I relate very much to that, when she’s told, ‘You’re not going to be able to play that role, you’ll be too old for that.’ I mean, she was told her career was over at 39. I was never told my career was over, but there wasn’t really a path that was set for us as women going, ‘Well, what do we do now?’ So, a lot of those things struck a chord with me. Like having my own production company and not really enjoying the business side of it at all but having to go, ‘OK, well, how do you budget a film? How do you negotiate a location? How do you support the creative process?’ Those things I’ve had to learn, and no one’s taught them to me. So, there’s been a lot of trial and error. Failing, then getting back up and falling down again.”

She laughs once more, warming to her theme. “But on the other hand, I just love the work. I actually would love to get up at 3 a.m. like Lucy does, and work on a scene. I often wake up in the middle of the night thinking, How am I going to do this? It literally just happened to me last night. I’m about to go and finish a show that’s having a few stops and starts because of the pandemic. But I woke up in the middle of the night going, ‘Oh, now I understand that scene.’ It came to me through a dream. So, it’s that sort of weird obsession. Those are things I totally relate to: ‘Keep going, try to get it right. Try to find it, try to find it. It’s not working. It’s not working. Stay in it, stay in it. Keep trying, keep trying.’ All of that.”

Hearing Nicole Kidman—four-time Oscar nominee Nicole Kidman, who won in 2003 for The Hours—talking about her “downs” is jarring. Surely, her career has been pretty straightforward? “Oh, but that’s sort of smoke and mirrors. When I got pregnant [in 2007], I thought, OK, well, I’ve been pretty lucky. I’d worked with some of the greatest directors, but there wasn’t a lot coming my way. I don’t want to go and shine a spotlight on the downs but let me tell you: I’ve had to create a lot of those opportunities myself. I mean, Big Little Lies came out of a dearth of work—there wasn’t really anything there. And strangely enough, it was my mother that pulled me out of it. I said, ‘Well, I’m pretty much done then, I think.’ And she was my Desi. She was like, ‘No, you’re going to keep going. I see things in you, you still have stories you have to tell. And I don’t think you should just give everything up because you’re having a baby.’”

Is that a damning indictment of the roles available to women in the film industry right now? “Well, not right now,” she counters. “I think there is a big swell of support right now, and this film is a perfect example of that. This film is about Lucille Ball, primarily. It’s about her marriage, but it’s also very much her story. Like Big Little Lies, all of those things—they’re stories, primarily about women, that have gone through the roof in terms of people watching them. Which is such a blessing, because it validates the necessity for them, you know? And that’s all you need— you need the validation in terms of people and the companies around going, ‘Oh, OK. Yeah, you’re right. That can work.’ And on this film, we were lucky to have the support of Aaron Sorkin. He comes in and writes this script—and knows how to write it because he is a writer, and he did do a show 36 weeks of the year, when he was doing The West Wing— and he gives that voice to Lucy. He doesn’t give that voice to Desi. He gives it to Lucy.”

The current swell of support has also been kind to director Jane Campion, who directed Kidman over 25 years ago in Portrait of a Lady and is currently riding high on the Oscar trail with The Power of the Dog. Is a reunion finally on the cards? “No, just plans to take long hikes with her. I have a very strong friendship with Jane, separate from anything professional. So, I would take a long walk with her through the mountains of New Zealand right now. She’s coming back to Sydney, so I plan to walk and talk with her. I’d love to, yes, move into her world professionally at some point. But I’m happy just to be in her personal world as well for the rest of my life. But there are so many people I want to work with. I’m kind of like, ‘OK, lead me somewhere now.’ I’ll keep my eyes and ears open, and my heart open, to where I might go next.”

What is next? “I’m not doing anything after this. I’m working with Lulu Wang right now. And then I’m footloose and fancy-free. Yeeeeah! Who knows what’s next? It’s kind of… yikes! And kind of exciting as well. Free-falling.” The show is called Expats, she explains, written by The Farewell director Wang and Australian writer Alice Bell. “There’s a number of other women who’ve been in the writers’ room on it, but it’s Lulu’s vision and it’s fantastic. I reached out to her and we kind of joined forces and we’re on a ride together right now. Her voice is so strong. She’s an auteur—a complete auteur.”

Like Bardem, Kidman thinks directing a movie of her own is a long way off. “I’m not good enough,” she says. “I’m good at contributing, but I don’t think I’m good at making decisions.” It is possible, however, that she might one day write a script. “I do write. Maybe I’ll write something at some point. I mean I’ve written things. I have ideas. I’ve written short stories. I’ve kept journals. So, I do write. Part of my release, actually, is just writing things.” She laughs. “Not necessarily for public consumption!”

What will she do when Expats is over? Will she start getting restless? “No. I’m just sort of taking care of my daughters, my husband, and living some life. Real-life, not a creative one. Even though they do intertwine.” Did Lucille Ball ever get to do that? She smiles. “I think so. She married a man who seemed very, very loving and kind, and I think she was very happy with him. I think she found peace with him.”

Best of Deadline

Cancellations/Renewals Scorecard: TV Shows Ended Or Continuing In 2021-22 Season

New On Prime Video For January 2022: Daily Listings For Streaming TV, Movies & More

Winter Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.