Lost ancient Greek star map discovered hiding in religious text

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1984’s The Last Starfighter, Alex Rogan became a video game champion and savior of the galaxy when an arcade game called Starfighter opened a path to cosmic adventure. So many of us dream of visiting the stars like Alex, but before we can do that, indeed before we could even explore the stars, we first needed a map.

That’s something astronomers have been attempting to do since before the invention of the telescope. It has long been believed that the Greek astronomer Hipparchus attempted to fix the stars in place by constructing a comprehensive map of the night sky in the second century BC. His work was referenced by others throughout the centuries, but historians had never actually found a copy of his work. Until now.

Biblical scholars from Tyndale House at the University of Cambridge were studying the Codex Climaci Rescriptus in 2012 when they discovered some astronomical content hidden beneath the main text. The codex’s astronomical content became sort of a side project while researchers continued their focus on the biblical text. Then, in 2021 Peter Williams — also of Tyndale House and co-author of a new paper published in the Journal for the History of Astronomy — recognized numbers and the notation for degrees among the astronomical text. He realized he was looking at star coordinates and brought Victor Gysembergh, research professor at the French National Center for Scientific Research and the Léon Robin Research Center on Ancient Thought.

RELATED: NASA captures the whole universe in illuminating decade-long timelapse

The star data was hidden from view because of the nature of the manuscript. The Codex Climaci Rescriptus is a palimpsest, a manuscript made of parchment which has been erased and reused over time. It contains layers of text, each less visible than the last, and deciphering the lost writing is a considerable challenge.

“It was relatively common to erase parchment, which is very durable but also very expensive because it’s animal skin. A book is more or less equivalent to a herd of animals, that gives you a rough idea of the cost. Making a palimpsest was fairly common for economic reasons whenever there was a shortage of parchment in a certain time or place,” Gysembergh told SYFY WIRE.

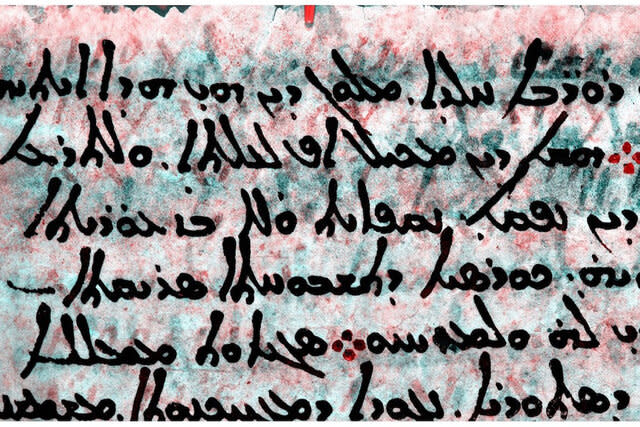

In this case, Hipparchus’s star mapping data was erased and written over by a Christian text known as the Ladder of Paradise, an appropriate name for the content it was hiding underneath. To get at the lost writing, researchers used a specialized imaging technique called multispectral imaging. Over time, ink is laid down on parchment, erased, and written over. Those layers all interact with the parchment in different ways. Things like the type of ink being used, the pressure the writer applies to the page, and how effectively previous writing was erased, all mingle together to create a mishmash of visible and invisible markings which multispectral imaging can disentangle.

Detail of f. 53v (multispectral image, by the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library and the Lazarus Project of the University of Rochester processed by Keith T. Knox: the enhanced Greek undertext appears in red below the Syriac overtext in black). Photo: Museum of the Bible Collection

“All of the differences show up in the way the light behaves when it is shone onto the parchment at various wavelengths. In effect, text that is not visible to the naked eye is made visible by the imaging and image processing,” Gysembergh said.

In this case, researchers used multiple methods to gather as much data from the parchment as possible. They looked at how light reflected off the page, how light was re-emitted in a different wavelength — a process known as fluorescence — and they looked at how light transmitted through the page. That data, combined with image processing, serves to translate erased writing into something scientists can read.

What they found, once all the imaging work was done, were fragments of Hipparchus’s famed star maps. “The text we were able to uncover is a description of the constellation Corona, the Northern Crown. It describes the length and width in degrees. Then it gives coordinates for the extreme stars, the northernmost, southernmost, westernmost, and easternmost stars,” Gysembergh said.

The finding confirmed what historians had long suspected, that Hipparchus did in fact map the night sky and at least part of that map existed, as thin as that existence may be, inside this ancient palimpsest. Not only did Hipparchus map the stars but he did so with stunning accuracy. When researchers rolled back the clock and put the stars where they would have been during Hipparchus’s lifetime, they found that his coordinates were surprisingly accurate.

“One must bear in mind that he was doing this with the naked eye. If he had instruments, they did not have magnifying elements. His measurements are surprisingly accurate, to an order of one degree, which is as good as it gets with naked eye astronomy,” Gysembergh said.

Granted, there may be some statistical noise in that claim. So far, they’ve only recovered fragments of Hipparchus’s map and it’s entirely possible that the next coordinate they uncover could have some greater errors. In the meantime, researchers are on the hunt for more of the map.

“We have reason to think there are fragments of Hipparchus’s star catalogue on other pages of the manuscript that we haven’t been able to read. We hope through more imaging and more image processing we can recover those. Another place to look would be in Saint Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt, where the manuscript probably originated. Other pages could have been recycled in other palimpsests,” Gysembergh said.