How Loro Piana Spun the World's Most Elusive Baby Cashmere Sweaters

You have to zoom in pretty closely on Google Maps to learn much about Alxa (or Alashan) Zuoqi, located in China’s autonomous Inner Mongolia region. From high up, its main town, Bayanhot, is a tiny smudge of concrete perched on a bleak moonscape of gray rocks and yellow sand that cling to the western fringes of the Helan mountains, as if in fear of what lies beyond. Which is not very much. This southern swath of the Gobi desert is home to a sparse population of wildlife (and plants, for that matter) and a lot of sand dunes.

At ground level, the town is altogether less attractive, a confusion of ornately depressing apparatchik hotels with rock-hard beds and—most likely—listening devices embedded in the lampshades.

Feral dogs skulk around the deserted car park, looking for things (or possibly people) to eat, perhaps singling out the weaker ones from the mixed crowd that appears here early each morning to perform a desultory cross between tai chi and breakdancing to music from a single blaring speaker.

It’s good to get out of town. On its dusty fringes, small herds of domesticated Bactrian camels forage freely. Here, Wednesday comes with two humps.

The desert—and you’re in it before you know it—is instantly beautiful and menacing. It’s the least likely landscape, you might think, in which to find the most sumptuous thing fashion could put your way. And yet it’s exactly this environment that created the ideal conditions for Capra hircus—specifically, the cashmere goat—to evolve into the G.O.A.T. of small-batch luxury.

Survival here, as any camel will tell you, hinges on adaptability. Over millennia, the cashmere goat has developed its own canny layering system for dealing with temperatures that can range from well below freezing in the winter to sweltering in the summer. The goat grows its wool in two layers: a coarser outer layer and a much finer inner layer. The thick outer layer is naturally shed at the beginning of the summer, and in June, the inner fibers are exposed.

It was this unique quirk of evolution that prompted Pier Luigi Loro Piana, of the illustrious Italian textile family, to create the brand’s baby-cashmere program 11 years ago (after ten years of painstaking research). Using only the belly fibers combed from baby goats once in their lifetime, the process yields just 30 grams per animal. The fibers are a mere 13.5 microns thick, compared with the positively chunky 15 microns of those from adult goats. (A human hair, in contrast, is about 100 microns thick.)

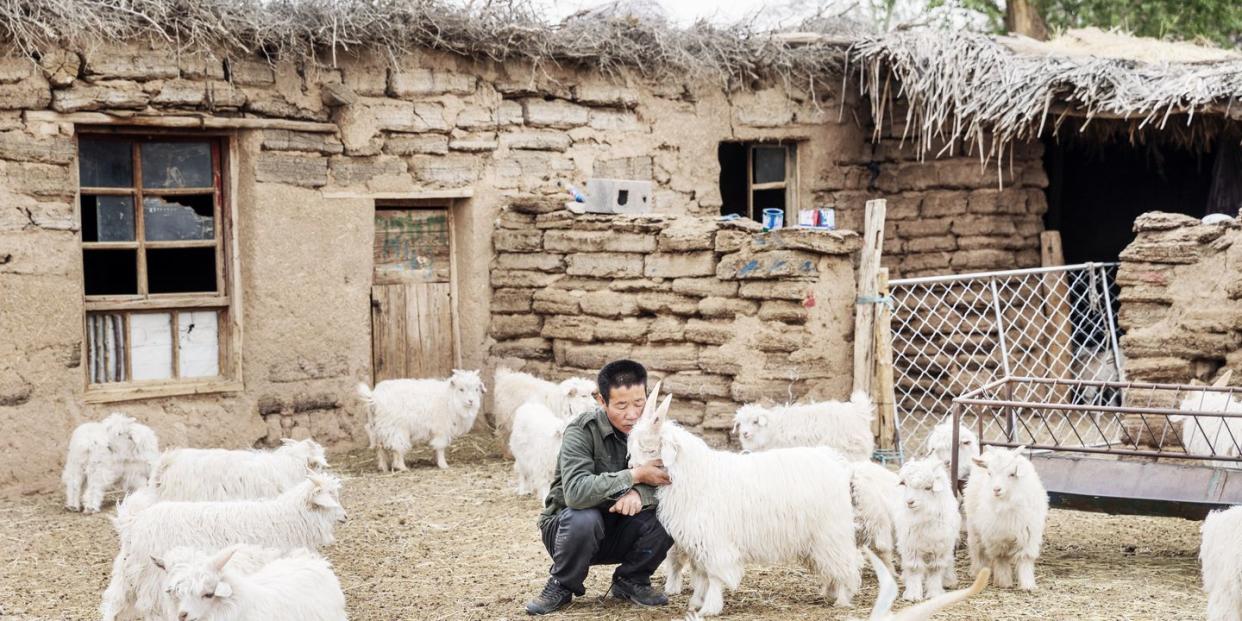

Local brokers gather the fiber from isolated farms, mudbricked but outfitted with satellite dishes, Land Cruisers, and (mercifully) a gleaming hospitality yurt. In these remote locations, herds max out—by law—at 200 head. It’s the Chinese government’s attempt to limit the effects of grazing on an already sparse landscape.

After dirt and coarser fibers are removed through washing and combing in a low-key plant on the outskirts of the main town, the weightless clouds of new cashmere samples are shipped to Borgosesia, in the foothills of the Italian Alps, where Loro Piana tests and grades them by eye, by hand, and by scanning under an electronic microscope before buying the finest and purest of the lot.

Spun and knitted in Italy, the baby cashmere is used for a small range of superfine sweaters in a number of colors, with a starting price of $1,195. If you ask us, the ones that come in undyed snow white or pale beige—the colors closest to nature—can’t be beat.

Given the scarcity of the fiber and the great distances it has to travel, these are always going to skew expensive. But if you’ve got the dough, along with a taste for the finer things, there’s perhaps no better sweater.

This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2019 Big Black Book

You Might Also Like