The Long Damage of Human Want

John squeezes sideways through a slim slot in the Utahn stone, his shirt rasping against the rough surface of the red rock canyon, its walls baking with the desert summer's heat. On the other side of the slot waits a high-walled cul-de-sac of stone, a roofless chamber gaped toward the sun and the wind, its floor piled with hundreds of sun-bleached bones, startlingly white femurs and skinny ribs and cracked skulls. A bone might last forever in the desert, but it's not the bones John has come to see. Painted across the chamber's red rock walls are varnished figures, tall black smears of charcoal, once-colorful inks blanched gray by time. Nearly every figure is male, each is an exaggeration of a man: men running, men hunting, men worshipping, raising lanky arms to a distended sun, their torsos overly long, limbs stretched and unarticulated.

Giants of a vanished earth, giving praise to a world now gone.

John’s come to stand among them, to confront their remains. He traces the black lines of the petroglyphs, their meanings opaque, untranslatable. Whatever the original intent, eventually the mode of every sign becomes elegy, even ink scraped into timeless rock. John kneels, scattering bones and stones, then runs his hands through the dust.

In the quiet, he stands, wiping his hands on his jeans, then turns in a circle to take in the paint and the bones, one more time. Maybe it's too late for him to feel what he thinks the people who worshipped here must've felt: to be of the world, not against it; to live with the plants and the animals, not apart or above them. It's not so easy to shake off his culture, his fading but still omnipresent civilization, despite all it ruined and wasted, despite knowing all he knows about what it's cost, what it will continue to cost; maybe he won't ever be able to feel at peace with the world, or at home in it, not as he desires.

Maybe not. But what he does next doesn't have to be for him. Maybe all he and his friends can do is keep trying to give the world back to itself, to continue to free whatever they can from the long damage of human want.

John's pilgrimage continues. The next morning, he drives north into Wyoming, through the Grand Tetons toward what was once Yellowstone. At the park's southern entrance, he retrieves his boltcutters from the truck's bed, then cuts the chains sealing the gate. His presence here is a crime unlikely to be punished, the Park Service already shuttered ten years, but still he notes the solar panels powering roadside wireless readers, there to record his ID and report his trespass, a sure danger if he hadn't already disabled the pebble buried in his right hand, that inescapable bit of Earthtrust tech embedded now in nearly every American body.

Earthtrust. After the catastrophic California earthquake finally struck, it was Earthtrust who pushed an emergency funding bill through the last true Congress in Washington, a rushed order seizing all lands west of the Mississippi; then using eminent domain and the president's emergency powers to create the Western Sacrifice Zone, a long-planned takeover waiting only for the right shock: half the country abdicated and sold to Earthtrust for dollars an acre by a weakened government busy fleeing to dryer land in Syracuse.

"We hoped these days would never come. We promised to be prepared for when they did," Eury Mirov had said then, the Earthtrust director's broad smile flashing from the country's every telescreen. "Now we are ready. Now we are coming to the rescue." Two weeks later, unmarked convoys of soldiers and squadrons of lifter drones swarmed the West Coast, rescuing whoever they could—whether or not the victims wanted rescuing—and evacuating them to resettlement camps hastily erected in the Mojave, then to Ohio, where the first Volunteer Agricultural Community was being built even as Oregon and Washington seceded.

In those days, John had been in Ohio too, with Earthtrust, with Eury. In the first months of the country's collapse, he'd felt constantly off-balance, unable to understand how Eury had moved so fast, carrying out previously unspoken plans with a brutal tactical efficiency he hadn't realized she'd possessed. When he left her company, years after his first misgivings, it was into the Sacrifice Zone that he'd fled with Cal and the others also quitting Earthtrust, all of them together promising to somehow one day push back against the future Earthtrust and the other megacorps were making. He hadn't wanted to meet violence with more violence, like Cal had. When, after years of begrudgingly giving into his objections, she’d finally decided to start attacking the Earthtrust security forces she’d once served in, he’d refused, leaving rather than going along.

Maybe he would go back. Maybe not. He thought he’d long ago lost what little nerve for direct action he’d ever had. All he’d wanted now was to atone for his part in what had already happened, for the world he'd help bring into being.

He arrives at Yellowstone's Lamar Valley by noon, parking his truck at the top of a narrow ridge overlooking the river. Thirty years ago, John's father had brought his son here to share his own awe of this greatest of America's preserves, the size of its wild-enough herds, buffalo and elk and bighorn sheep, the promise of spotting wolves at dawn; now the Lamar Valley's previous beauty has become a starkness unbroken by movement, its emptiness a bleak power. He tries to picture a long ago day spent here with his father, the valley as it was before the parklands were emptied of people with the rest of the Sacrifice, hundreds of bison entirely uninterested in the encroaching crowds—but when he scans the opposing bank's tree line, his gaze meets not the bison he craves, but instead the narrow wedge of a wolf's curious face, impassively peering from the pines.

John startles. He knows he shouldn't approach—the wolf's a hundred meters away, atop a steep embankment on the opposite side of the river—but he can't help himself. How lonely he's been, how devastated he's become by his aloneness in the months since he last saw Cal or any of the others he'd come west with; his loneliness colors every empty landscape he visits, anywhere once home to more bountiful life. He fords the river, splashing loudly, the wolf already backing away from the tree line. Slowed by his sloshing boots, John clambers atop the ridge, pulling himself up by the fracturing branches of the dry pines; he's soon out of breath, breathlessly hopeless. Likely the wolf was never there. Just more wishful thinking, in a world quick to punish such thoughts. But then he finds it again, twenty meters away: the wolf, gray-furred, steel-eyed, healthy enough, with no sign of mange or malnutrition.

The wolf permits John's gaze, gazes back. Then it begins to nose through the grass at something John at first can't quite see, then can't look away from: surrounding the wolf are the corpses of dead bison, erratic boulders of shaggy fur.

John approaches slowly, wary of the wolf and its snuffling progress. He counts a dozen giant bodies, then glimpses more partially hidden by the rustling grass. Through the tall cover, he sees an unnervingly large yellow eye, open and staring, jaundiced and bloodshot; it’s all he can see of a massive head except the curve of one broken horn, the rest of its bulk obscured. The eye is cloudy, staring at nothing, so that John thinks this bison is dead too—but then the eye moves, rolls crazily in the broad black-furred face.

He cries out, unnerved; the wolf continues to pace nearby, unperturbed, its tongue lolling loose between its teeth. He carefully pushes back the grass to reveal the unbelievable bulk of the injured animal, its hooves jerking dreamily, its body rocking in the dusty earth as it tries and fails to stand. It’s a last juvenile, orphaned and alone, its stout ribs pressing through stretched skin and matted fur, its bold shoulders too atrophied to lift its heavy skull.

He kneels, rests his hand on the bison's bony crown. The wolf lingers nearby, packless in this valley where the most successful reintroduction program in the country once thrived. It stalks uncannily from corpse to corpse, nosing each of the dead bison in turn, sniffing and prodding but not eating. John stands, determined to shoo the wolf away from the juvenile, but as he rises, he hears, distant but closing fast, the telltale sound of approaching rotors.

John flees back the way he came, sliding down the slope, feet clumsy in wet boots; he hits the river fast, slipping into the shallow water, crashing over loose rocks. Above him a dozen drones fly over the ridge, heavy lifter quadcopters with bright yellow claws dangling underneath, arrayed in formation around a cargo drone the ungainly size of a dump truck. The noise is incredible, the downward thrust of the drones' rotors flattening the prairie to expose more corpses alongside the barely breathing juvenile and the improbably calm wolf. The heavy lifters descend, belly-mounted winches dropping claws on high-tension cables, their serrated jaws opening to dig into dead weight. One by one they ferry the bison into the cargo drone's open hatch, its bulk swaying and dipping with each catch, until one final drone lowers itself over the last living Yellowstone bison.

He forces himself to watch. The juvenile bellows a sustained cry, guttural and grieving as it struggles against the steel claw, its hooves running futilely on air until the drone deposits it among the massed dead of his herd. John hears the creaking cargo doors closing, then the heavy rushing wind of the drones turning in formation. Soon the sky is empty, not even a cloud remaining to color the sunset. Once again the voice of the world reduces to the howl of hot wind crossing the lonely expanse of the Lamar Valley, rasping the thrashed and flattened grasses where the bison laid down to die. Only the wolf remains on the ridge, sitting on its haunches, staring at John, its expression blank but its eyes alive, watching.

When it rises and trots away, headed in the same direction the drones fled, John begins to shiver, his skin goosefleshing. It's one hundred degrees in Yellowstone today, one hundred degrees at least—but once John begins shivering he can't stop, not for a long time, not until his anger once again overtakes his fear.

From that anger, John knows, sooner or later he'll have to plant a bomb.

For five years, he's done this. Wherever he travels, he looks for chances to blow holes in dams over dry riverbeds, to use the truck's winch to tear down anti-erosion embankments bolstering curves of freeway, to rip free chainlink fences from litter-strewn roadsides. The gutted cities, the thousands of kilometers of empty concrete claiming the earth for the no one there. John's task is endless and likely futile; he tries anyway, believing nature could reclaim what humans had taken, as long as you gave it somewhere to start. The damage will not be undone in a year or a decade, but with human inhabitation leaving the West, the rest of nature might be given a chance: there are no herds anymore, the tens of millions of antelope and bison destroyed, but someday there might be new migrations, other species filling in the human void.

This is what John wants, what he followed Cal west to try to make real: a rewilding of the West, beginning with a dismantling of the human ruins.

The highway leading south from Yellowstone is officially closed and theoretically vacated, the asphalt in disrepair but serviceable enough. The truck's bed holds the makings for improvised weaponry, bags of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, canisters of gasoline, left-behind blast caps and pilfered sticks of tovex. Fossil fuel explosives to undo a fossil fuel economy, to break the infrastructure left behind when everything west of the Mississippi became the Sacrifice Zone, half a country forcefully evacuated so American lives might flourish elsewhere.

Whatever might be reused, John wants destroyed. If the steel was left to be recycled, it would only be made into something else, some new construction, some other machine. John doesn't want more machines, more telephone poles and wind turbines stabbed into the landscape. He wants precious minerals and untapped oil left in the ground, he wants water to flow only where it wants to flow. No more unregulated unrestrained extraction, no more conservation in one place making expansion possible somewhere else.

At day's end, he idles upon the outskirts of Rock Springs; dusk falls over dustbowl fields, the sun's last light gives glow to unpowered fast food signs. Across the street, he spies a signal he'd pretended he hadn't been seeking, a direction and a number spraypainted in bright orange on the side of a burned-out diner. He pulls the truck into the trash-strewn back lot, kills the ignition, lets the engine tick to a stop. How many months has it been since he's seen a blaze this fresh? He'd recognize the graffiti handstyle anywhere, the orange numerals two meters high obviously Cal's, the arrow slashed below them making for a clear enough message pointing John forty-five kilometers east, even though the arrow points west instead: as Cal always says, sometimes the slightest simplest misdirection is enough.

Tapping his foot, John scans the nearby buildings, the distant horizon. He listens: nothing and no one, only the dusty wind, a distant creaking of rusting metal. No one now, but Cal was here, not so long ago. Cal wanting to see him, calling him back to her.

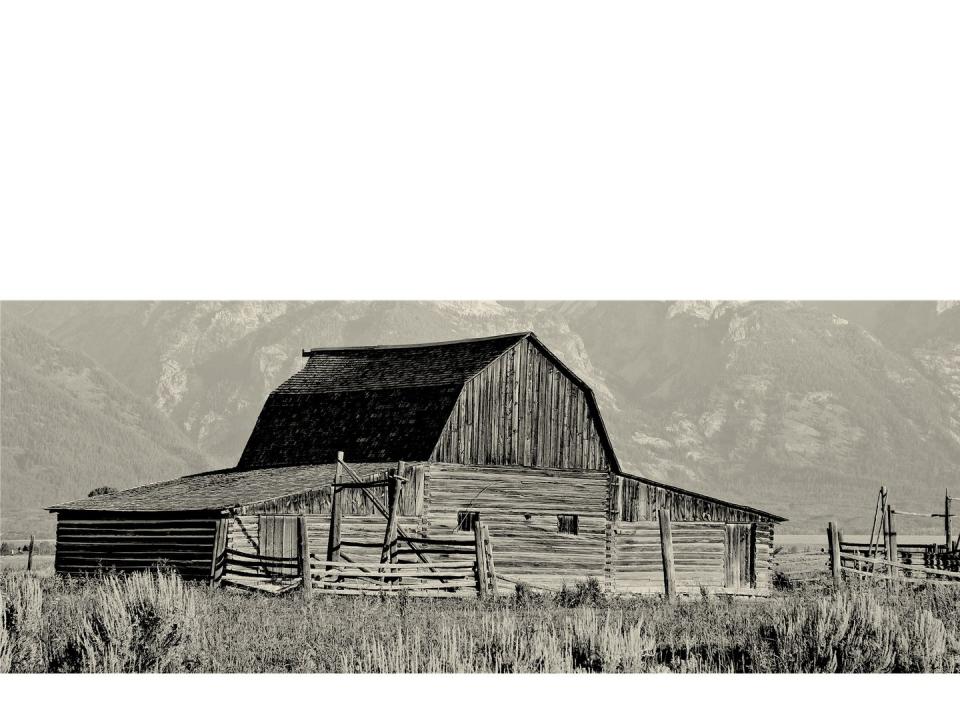

He drives, faster now, following the blaze's directions; he leaves the highway for surface roads, concrete giving way to dirt as he crosses dead farmlands, fields of what was once barley and wheat and corn, now only hard clay punctured by toppled wind turbines, most of their masts felled not by human hands but by unpredictably violent weather. He finds the next blaze twenty kilometers northeast, exactly as directed, follows its order past more-recently scorched splotches of infrastructure, many bulldozed kilometers of chainlink fence, a stretch of highway jackhammered vulnerable to erosion and frost. The spraypainted distances keep going down, the blazes get smaller then disappear. Close now. He knows what to look for: he turns onto a gravel road beckoning north, then follows a dirt road veering east toward a husk of a farmhouse beside an intact barn. He pulls in, parks beneath the questionable shade of a leafless oak; he runs his fingers through his hair, scrubs his sunburned face with filthy hands. This time, when he rolls down the window, he hears clanging coming from the other side of the paint-stripped barn, a sound he follows to find Cal working in the structure's narrow shade, Cal bent beneath the hood of her gray Jeep, her broad shoulders bunching with muscle.

Cal pauses her work, sets her wrench down carefully atop the oily mass of the engine. Even at rest she exudes an unruled energy: a violence in fatigue pants and a sleeveless undershirt. "Hello, old goat," she says, without turning. He moves behind her, mirrors her posture, placing his hands beside hers on the lip of the hood, their hips close but not touching. Cal's body coils beneath his, poised, tensioned but not tense; John smells motor oil and trace explosives, her sweat, his own. He shifts his hands to overlap hers, knows she'll already have moved before he touches her. She twists beneath his leanness, her muscles rippling, she puts her mouth on his, then drives him to the ground, abruptly straddling him, her solid weight pinning his lean body to the clay exactly as he'd hoped she would.

Inside the barn, Cal shows John the rare refuge she's found, hidden by a steel hatch concealed under a dusty layer of hay and chaff. At the bottom of a narrow ladder waits a spare concrete room, an emergency shelter with a bunkbed, a store of nonperishable food and medical supplies, a tank of potable water. John's immediately claustrophobic, but Cal shushes him, pushes him toward the corner shower. The water is rusty, stale, magnificent, stinging John's sunburned skin, streaming over Cal's stout musculature. The concrete muddies, the mud clogs the drain, they kick to clear the flow with their toes, playfully at ease. Afterward, John goes naked to his truck, enjoying the hot wind wicking away the shower's moisture, his body dry by the time he returns to the barn in clothes at least marginally less dirty than the ones discarded below.

Instead of returning to the bunker, they sit at a plastic folding table Cal's dragged near the barn's entrance. The barn's interior is dim but for now they light no lamps, unwilling to signal their presence by lighting the one glowing structure in this sunset country. Famished, John devours the simple meal Cal offers him, the first hot food he's had in weeks. He sighs at the honest pleasure of rehydrated beans and rice heavy with preservatives and salt, a tumbler of cool clear water tasting of the tank, all of it a joy after the austerity of protein bars and boiled water.

"How did you find this place?" he asks, sporking a second bite into his already-full mouth.

"I was working my way down the Dakota fracking fields, disrupting pipelines and breaking whatever I could," says Cal, stirring her own food but not yet taking a bite. "You can probably guess what there was to see. Fleets of oil company trucks left behind when the wells went dry, office buildings filled with recent enough computers, already junk. Kilometers of server cables, electrical wires, leaking pipes. I found a bulldozer and used it to topple telephone poles, push over fence lines, break up the roads."

"More terrorism," interrupts John, making air quotes with his hands. That's what the federal government in Syracuse calls it, unwilling to recognize rewilders as separate from the rebel groups roaming Wyoming and Montana, locals or new arrivals kicked out of the free Northwest: Bundyists with automatic weapons claiming swaths of land as patriot preserves, driving smokestacked pickups across the broken clay; bands of polygamists unwilling to be taken east, clinging to the strip of wasteland between what was once Arizona and Utah; the Navajo Nation and the other rightful owners of the Southwest, sovereign peoples refusing to be moved from their lands, to ever be relocated again. If Cal and John are terrorists, they aren't the kind of terrorists who'd burned Reno to char; they aren’t the sort who'd detonated the crude oil tanks outside Houston, who'd set fire to the reserves stored below, setting off an inextinguishable underground blaze that had hastened the city's evacuation.

"I stopped to dismantle a fuel station in South Dakota,” Cal continues, “taking apart the pumps and sealing the tanks before spending the night inside. In the morning, I woke to a truckful of Bundys parked outside, going through my Jeep. I saw one holding up my clothes, watched them figure out what they'd found. A woman, traveling alone." She smiles, leans back, crosses her muscular arms. "I knew it wouldn't take them long to figure out where I was. I snuck to the nearest ledge, lifted my rifle into position."

"Cal," John says softly. "I don't need to hear this."

"You asked how I found this place. This is how I found it." Cal mimes firing her rifle, three-round bursts taking each of the four men surrounding her Jeep in order, Cal working left to right, only the last man reacting in time to reach for his own weapon. "There was a map in the truck's glovebox. They were scouts, sent from Nevada to look for supplies, possible outposts. They'd marked this bunker in pencil, so I figured it was a new discovery: if they never made it back to base then no one else would know it existed. That afternoon I started working my way here, looping the long way around in case I was followed." She smiles again, her big teeth shining in the dark. "And also so I could leave a path for you."

Finished eating, they sit quietly, John rapping his knuckles on the table, knocking to open a door inside himself. "How'd you know where I was?" he asks, which is not quite the question he meant to ask. What do you want, he might've said.

Cal laughs, husky, deep-throated. "You didn't want to find me, old goat?"

"You know I did," John says, flushing, moving away as she leans forward, her hands pushing across the table. "But what if I hadn't seen your blazes?"

"Then I'd be fed and showered and unfucked, and you'd be dirty and stinking and sad as ever." She pushes her scraped food tin away. "But you're right. There's more. It's time to go back east, John. Time to go see your girl."

Eury Mirov, Cal's enemy; John's too, if he believes what he's supposed to believe. Defending Eury to Cal has always been pointless, the anger she put in Cal permanent, scarring; Cal fought for Earthtrust too long, did too much she regrets. John's woken her from screaming nightmares that left them both gasping terrified in their tent pitched on some windswept plain, the back of John's truck beside an empty highway, a dusty bed in an abandoned motel, some cramped room swept free of the carapaces of starved cockroaches.

Earthtrust—it's always Earthtrust. John tells Cal about Yellowstone, about the strange wolf he saw there and about the drones taking away the dead bison. "What were they doing?" he asks. "What could they possibly have wanted?"

Cal unrolls a laminated topographical map of the west, its mountains and rivers bounded by the borders of political divisions now defunct. "I don't know," she says, gesturing at the reset country marked with fresh scribblings of permanent marker, colored pen. "But I saw Noor in Montana a month ago. She reported seeing Earthtrust dronedozers gathering up fallen trees draped in tents of invasive moths in one place, dredging dry lakes in another, the machines moving right down the middle of empty riverbeds. Everywhere she went, everything dead or dying was being gathered up, taken away."

"For what? What do they want with dead trees? Earthtrust barely even builds with wood. Almost every building in the VACs is printed concrete, extruded plastic."

Cal throws up her hands. What good are his questions, which they can't possibly answer?

"At least Noor's all right," John says. “Where are Mai and Julie?”

Cal fills him in: Mai is back at Earthtrust, returned to the Ohio VAC's medical clinics, the only one of them who never directly resisted the company, the only one who'll be a citizen of the United States the next time they all meet. As for Julie—"You heard about the Cochiti Dam explosion?" Cal asks, rising from the table to pull back a tarp tacked to the wall, revealing a stack of crates, supplies or weapons or both.

The Cochiti Dam: two hundred thousand cubic feet of earth and rock, five kilometers across the Rio Grande, just north of vacated Albuquerque. A month ago, someone set enough charges to blow the dam open, freeing what little river was left. It wasn't supposed to be easy to crack an earthen dam that size, but in the end all it took was effort and time, plus explosives.

"That was Julie?" John asks, already knowing the answer. Before the dam was built, the nearby banks of the Rio Grande had been inhabited by the Pueblo. This was land Julie's ancestors had stewarded and protected; blowing up the dam couldn't restore what they'd lost, but at least Julie could set free what remained. "Good for her," he says, and means it. He knew his family's land had been stolen from someone else, farther back than he could feel. Now it was lost to him too, all its soil blown away, that once fertile earth that had given generations of humans purchase.

"What are we doing here, Cal?" asks John. Maybe he knows but he wants to hear her say it. He'll do anything she asks, but he wants her to ask. "What's changed?"

Cal returns with a tablet computer, a wand trailing a fraying plastic cable gone yellow with age. At Cal's touch, the tablet begins its slow boot process, its software burdened by a series of hacks and backdoor workarounds keeping the device from pinging home.

"When we left Earthtrust, the Secession was ended, and the Sacrifice had long since cleared Congress. I'd dragged people out of their houses, loaded them into trucks and busses heading east; you'd made sure the VAC in Ohio was up and running, putting your supertrees and your nanobees to work." Cal's face leans over the tablet, her profile lit electric by screenglow: her chopped hair, the hard angle of her soldier's jaw, the twice-broken nose hung above the toothy glint of her smile. "But we both knew the VACs weren't the end goal, that Eury Mirov wouldn't stop there. We decided we didn't want the world she was bringing into being."

John nods, agreeing. But was that all he'd wanted? Was it always so simple as that? He thought of the genetically modified apple trees he’d designed, the synthetic insects he’d developed to pollinate them, all the other inventions he’d abandoned when he left Earthtrust to follow Cal. "I chose you," he says. "Me and Julie and Mai and Noor, we all did. The others too."

"And because of that," Cal says, "I've had to take responsibility for everything that happened. For everyone we lost." And they had lost: a half-dozen men and women who'd come west with them, then all the others who'd joined in the Sacrifice Zone, people who loved the land and wouldn't be removed. The first year had been spent running from Earthtrust security forces intent on emptying the west, the next dealing with the ever harsher conditions post-Secession, post-Sacrifice, amid the forever drought spreading beyond the southwest. But the community of rewilders had swelled, caravanning in four-wheel-drive trucks and SUVs. It became easier to protect each other and to do their work, everyone working together to dismantle larger infrastructure projects, to effectively scavenge abandoned city blocks. For a while, everything had gone right, or at least right enough. And then it hadn't, not ever again.

"I know, Cal. I'm not—" John pauses, not because he doesn't know what to say but because he's surprised to find out he means it this time. "I'm not angry anymore. We were always going to despair at the futility of it. And something was bound to go wrong, sooner or later." One summer there were algae blooms on every reservoir, leaving water that couldn't be safely filtered or boiled away; always there was unbearable heat baking their tents into ovens, never mind their hotbox RVs, whose solar air conditioners kept freezing from overuse. Three men drowned in a flash flood that washed away a camp in northern Arizona's red rock canyons, an unfortunate accident; it was so easy to die of exposure, it was so easy to fall and break a leg no one knew how to set, to succumb to a burst appendix no dared remove. When the group was half its largest size, it started being preyed on by bands of preppers and survivalists, attackers they could repel but not without cost. A family was separated by an Earthtrust raid that captured the mother and daughter, sending the father and son rushing after by motorcycle: better to be caught together than be free apart. A suicide set off a run of copycats until they were all watching each other, talking gingerly, trying not to fight as their health worsened, as their sunburns flaked, as their teeth loosened against the hard nubs of expired protein bars.

Everything west of the Mississippi was desert and those who stayed became desert creatures, stronger, tougher, leather-skinned—but not before years of struggle eroded their community down to its core.

Now it's Cal's turn to look away. "It doesn't matter if you forgive me for what I did, for what I chose for the rest of us," she says. "But I need you now, even if you're still angry. We knew some of what Eury had planned, knew what to watch for."

"You knew because I told you. Because I betrayed her."

"If you hadn't, we wouldn't know what's about to happen." Cal pauses, sets her jaw. "Pinatubo, John. Eury Mirov's actually going to do it."

This is what he'd been waiting for Cal to say, what he'd been sure she would, but still he doesn't quite believe. "There's no way the government will ever sign off—"

"Don't be naïve. She administers half the country. The cities would starve without Earthtrust, and most of the rural areas too. The same is true abroad now. With VACs everywhere, she owns the only crops anyone can make grow. Who can stop her, if she decides to go forward? You said once that however Pinatubo turned out, it'd need a delivery system capable of reaching the stratosphere. Mai says Earthtrust's built a huge facility at the Farm's center, a tower topped by a twenty-story needle aimed at the sky. An injection point, just like you said."

"Eury's had the idea for the Tower for years. But that can't be the most efficient way to—" John pauses. "Pinatubo was supposed to be a last resort," he says. Geoengineering on a global scale, locking the rising temperature in place for a generation, making a respite in which humanity could transition to a new economy and a new culture, then begin the long work of repairing the planet. A future intended to start on the Ohio VAC, built on the land where he and Eury grew up. Despite Eury's assurances, he'd never once believed Earthtrust would amass enough power to pull it off.

Cal raises her hands in mock retreat. "Earthtrust doesn't have to be an evil company. The Sacrifice Zone didn't have to happen, the Secession didn't have to be a bloodbath, the VACs don't have to be surveillance states, they don't have to force you to give up your citizenship to gain entrance. But all that happened on Eury Mirov's watch. Maybe there's reason enough to geoengineer the stratosphere too, but can we trust Earthtrust to do it right, for the right reasons?"

Only now does John realize Cal's waited to speak to him until last. Mai already in place. Noor and Julie meeting up, heading east together. The five of them made their plans for getting back into the Ohio VAC years ago. All they have to do now is carry them out. She leans forward, holding John's gaze. "Are you in, John, as you promised you would be?"

Her radiant intensity, her unwavering conviction—all of it overwhelms him. He has to look away so he can think his own thoughts, make his own decisions. "I'm tired," he says, quietly, after a moment's pause. "But yes, I still believe."

"Then are you ready to reenter the world of the living?" she asks, before reaching for his right hand, splaying it palm-down on the table: every Volunteer, every Earthtrust employee, every refugee or prisoner has an ID pebble embedded in the loose skin between their right thumb and forefinger. Cal taps the tablet screen a few more times, reactivating John's and installing the hacks Noor had crafted in anticipation of this moment, the day they all went back: a new identity that might hold up to Earthtrust scrutiny, plus a deep-seated series of hidden subroutines John can summon with the right sequence of hand movements and purposeful blinks. A row of dim white lights winks on beneath the skin, each light the side of a pinhead: indicators barely visible through the epidermis, used to communicate basic notifications. John squeezes his thumb against the palm of his hand until four of the lights flash: orange, purple, green, blue; Cal, Julie, Mai, Noor.

Only the five of them left, out of all those who'd gone west.

During his retreat in the parklands, after he'd last left Cal, he'd been alone, responsible to no one, or so he'd told himself: a sleepwalker, dreaming in the desert, despite the bombs and the makeshift bulldozing. Now, thanks to Cal, he was awake again, his solitude broken, his connection to her and the others restored; now he was ready, despite everything they'd done and everything that had already gone wrong, to do whatever it took to try to make the world they wanted instead of the world they had.

John squeezes his fist to watch the lights scroll their colors again; he opens his hand, then looks up to catch Cal's stare, finally able to match the determination he sees there.

Whatever else had happened, John had never wanted to abandon the world.

Adapted from APPLESEED, by Matt Bell.

You Might Also Like