A Long Beach-born painter captures the surrealism of the Cambodian American experience

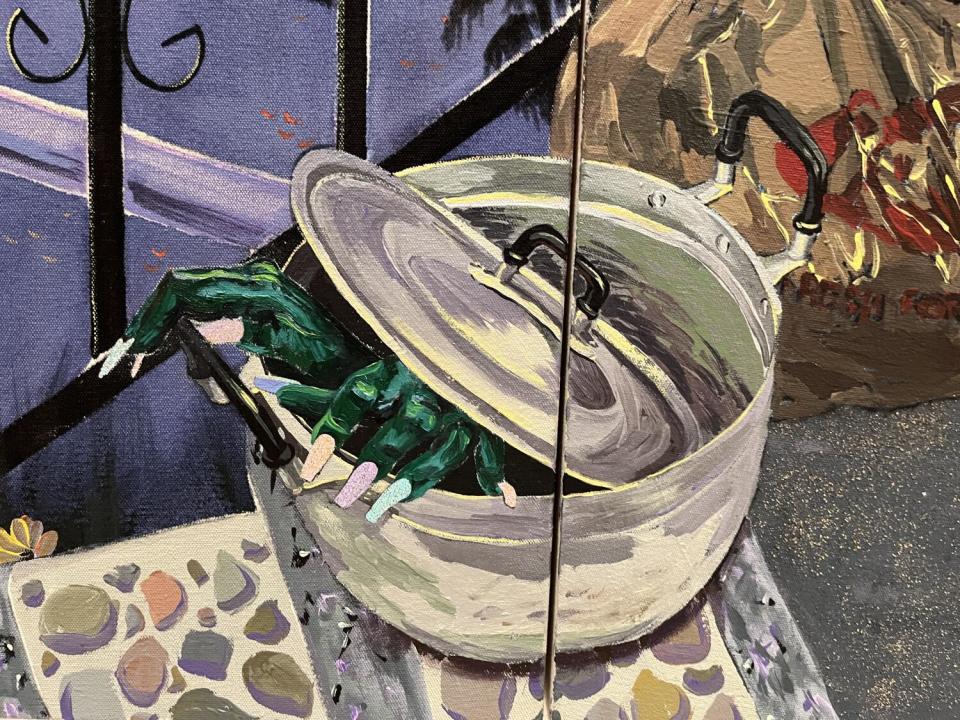

The first thing you notice about the paintings of Tidawhitney Lek is the hands. Hands slink around doorways and sofas and emerge out of closets and gutters. They play with the locks on your door while you are napping and cleaver banana plants in the middle of the night. Sometimes the hands are green; other times, human shades of brown. Always, they bear glittery manicures. Never is it revealed to whom these hands might belong or whether their intention is protective or sinister.

"People always ask me, 'Friend or foe?'" Lek says of the mysterious appendages. "I say, 'That's the idea.'"

The magic in Lek's work extends well beyond hands. On the surface, her paintings appear to chronicle intimate domestic scenes. In one canvas, a woman dozes peacefully on a couch; in another, two women linger in a lush garden. But look closer and you'll find details that unsettle. The sleeping figure rests on a sofa whose abstracted pattern evokes a swarm of winged insects. And the garden where the women idle isn't a single space but a vertiginous composite of several spaces whose angles defy the laws of physics.

No work of Lek's, however, disorients quite like "Refuge," a three-panel painting completed in 2023 that extends to a width of 12 feet. Now on view in "Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living," the sixth iteration of the Hammer Museum's biennial, it shows three girls, seen from behind, reacting to the bombardment of the Cambodian countryside in the 1970s. Give the canvas a fleeting glance and it might seem as if the girls are huddled behind a soldier in a rice paddy.

Read more: In blow to L.A. art scene, Hammer Museum director Ann Philbin to retire in 2024

But look again and you'll find that this wartime scene — inspired by the experiences of Lek's Cambodian father — is something else entirely. The explosion is actually rendered on the surface of a closet door in a mundane apartment where the girls sit next to a pink bucket and a sewing machine. Naturally, there is a hand: a gnarled, green claw that emerges from the depths of the closet, like a ghost of the past reaching into the present.

In Lek's paintings, rich colors catch the eye: sunsets in shades of Los Angeles toxic and lots of sparkling sampot — the traditional Cambodian wrap worn around the lower body. But horrors real and cinematic simmer just beneath the surface. Diana Nawi, an independent curator who served as co-curator for "Acts of Living," says Lek's work contains humor, "but it is also tied to this very real violence."

On a warm Monday morning in October, Lek greets me and Times photographer Genaro Molina with strawberries and freshly brewed tea in her sunny studio, located above a scrum of stalls selling succulents and bamboo in the Flower District. Hanging on walls and propped up against columns are a series of new paintings that will appear in "Living Spaces," a solo show that opens Friday at the Long Beach Museum of Art’s satellite exhibition space in the city's downtown. In one canvas, a hand with sparkling pink nails grips a door frame in a setting that confuses indoors and out; in another, a group of men in Western dress play a Cambodian dice game called klah klok.

For Lek, this is a moment of institutional prominence. Her paintings open the Hammer biennial just as she is about to have her first museum solo. But her success follows a period of searching — searching for the right visual language to articulate her experience as the U.S.-born daughter of Cambodian refugees who survived the horrors of the Khmer Rouge's genocidal regime in the 1970s.

"These paintings are my diaries," says Lek. "I'm literally in conversation with myself. What was yesterday? What is today? And what is going on tomorrow?"

Read more: Art made during — and despite — the pandemic informs the Hammer's 'Made in L.A.' 2023 biennial

Lek, 30, was born and raised in Long Beach to parents who emigrated from Battambang, in northwestern Cambodia. "I'm the first generation of an immigrant family that grew up really poor on Section 8," she says. "My mom has six kids. I'm number six."

In Cambodia, her paternal grandfather had been a tailor. On her mother's side, her grandfather had worked as some sort of merchant. "My mom doesn't say too much about her past," Lek says. "But she has said her father was a businessman. He sold and traded."

Lek's parent's were adolescents when the totalitarian Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia in 1975, emptying out cities and systematically killing the country's professional and intellectual classes. Nearly a quarter of the population (about 1.7 million people) died during its rule from violence, overwork and starvation. Her parents survived, but many extended family members did not.

After the Khmer Rouge fell in 1979, the couple made their way to refugee camps in Thailand and the Philippines. By 1984, they had relocated to the United States, living for a short time in Boston before settling in Long Beach, home to a large Cambodian diaspora clustered on the eastern side of the city in a neighborhood known as Cambodia Town.

Cambodia's history stretches back centuries and includes magnificent traditions in temple architecture and bronze sculpture. But the Khmer Rouge's four-year reign of terror casts a long — and often silent — shadow. "For school, we'd have these assignments where it's like, 'Go ask your parents what it was like when they were growing up,'" recalls Lek. "And they'd be like, 'Why do you need to do this?'"

Art was important to Lek from an early age. "Since I was a kid, I was the art girl," she says. "But my parents always told me that this was something that was not going to pay the bills."

Read more: In Cambodia Town, moving beyond the ‘killing fields’ and into success

After she enrolled at Cal State Long Beach in the early 2010s, Lek left her major undeclared, figuring she'd pursue art while preparing to become a math teacher. But a visit to New York City in 2014 upended that plan. That year, she joined a student trip led by painter and Cal State Long Beach professor Tom Krumpak that included visits to a multitude of artist studios. Growing up in Long Beach, she says, "I had never really been exposed to the contemporary art scene here." But the trip pulled back the curtain on that world. "New York," she says, "turned something in me."

Lek did not start out by painting her family. In school, she favored abstraction: "Brush marks, gradients, working with the texture of paint." But she wasn't sure how genuine it felt. She remembers one of her professors, painter Siobhan McClure, asking her: "Tida, why don't you paint who you are?" But Lek says she wasn't ready to reckon with that. "That was a time when I was still unhappy with where I come from and I was still digesting what it meant to own that."

But after she graduated in 2017, the artist began to come around to figurative work. In the months after graduation, she spent formative stints working in the studios of some Los Angeles painters, including Annie Lapin, Amir H. Fallah and Danielle Dean, which got her thinking deeply about color and juxtaposition of images. And she was seduced by Kerry James Marshall’s solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles in 2017. "I saw his retrospective at MOCA like three times," she says. "I was like, 'This is fantastic. I'm seeing this person in this whole group of paintings and how he manifests what is around him.'"

She began by painting interiors. "I decided that my home was the best place to start," she says, thinking of rooms as "stages" where a story could be implied. She then turned to her family. A key work, "Cutting Threads," from 2020, evokes the surreal nature of so many of the paintings that have come since: a pair of hands emerge from a television set and connect, via a tangled red thread, to another pair of hands operating a sewing machine. The scene was inspired by her mother. "She loves watching TV while she sews," says Lek. "That's why I put those things together."

The process of engaging her family led to conversations about their history. Her father, she learned, wrote an autobiography in Khmer and once slipped a copy of it onto the shelves of a local library. Now, he reads to her from it on occasion (a slow process, since Lek isn't very fluent in Khmer). The bombardment shown in "Refuge" was inspired by an anecdote from the book, in which her father attempts to locate his family in the middle of crossfire during the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

"When I started painting my family in my home, it was literally tackling things I'd been wanting to talk to them about," says Lek. "It's not until we make the paintings that we find room to address it."

Read more: Artist Alexandre Arrechea on architecture's hidden stories and that Black Sabbath ballet

Lek arrived at her singular style at a fortuitous moment. Last year, a solo show of her work at Sow & Taylor in Historic South Central caught the eye of the curators for the Hammer's biennial. Pablo José Ramírez, a staff curator at the museum who organized the biennial with Nawi, says Lek's paintings were among the first works they saw as they began the curatorial process. He says part of the danger of seeing a work early is that it can slip from memory when it comes time to decide on the list of participating artists. But Lek's paintings stayed with them.

"There is something worldwide with painting going back to surrealism now," he says. "The last Venice Biennale had a big section on surrealism. But this is the first time I've seen something like Tida's work."

Nawi says Lek's disconcerting juxtapositions force the viewer to ask, "Where are we and when are we?"

Lek says her success has reassured her family that she made the right professional choice. Though her older brother, in typical sibling fashion, was unimpressed when she told them that she was going to appear in "Made in L.A." "He was like, 'Hammer Schmammer, I don't know what that is,'" she says with a laugh.

Ultimately, what motivates her is not the institutional approval but the encouragement she receives from fellow Cambodian Americans, who find their truths on her canvases. "I have my community reach out to me via Instagram, or friends and family who I hadn't heard from," she says. "They're like, 'Yo, I saw your work. Keep telling our story.'"

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.