Loneliness is our deepest shame – can cinema help us confront it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Olivia Laing wrote the book on loneliness. Over a decade ago, the British writer moved to New York City for the love of a man who then called it off. She stayed and sought out artists who anchored her solitude to the city. “I was possessed with a desire to find correlates,” she wrote in 2016’s The Lonely City, “physical evidence that other people had inhabited my state”. The book was both a memoir and a deeply researched biopic of 20th-century artists, among them Edward Hopper and Andy Warhol, who lit up the sensation of loneliness.

There is a paradox to work that is created from an artist’s sense of dislocation – it can welcome the painfully isolated back into the human fold. As one of Laing’s artist subjects, David Wojnarowicz, told photographer Nan Goldin for Interview magazine, “We can all affect each other by being open enough to make the other feel less alienated.”

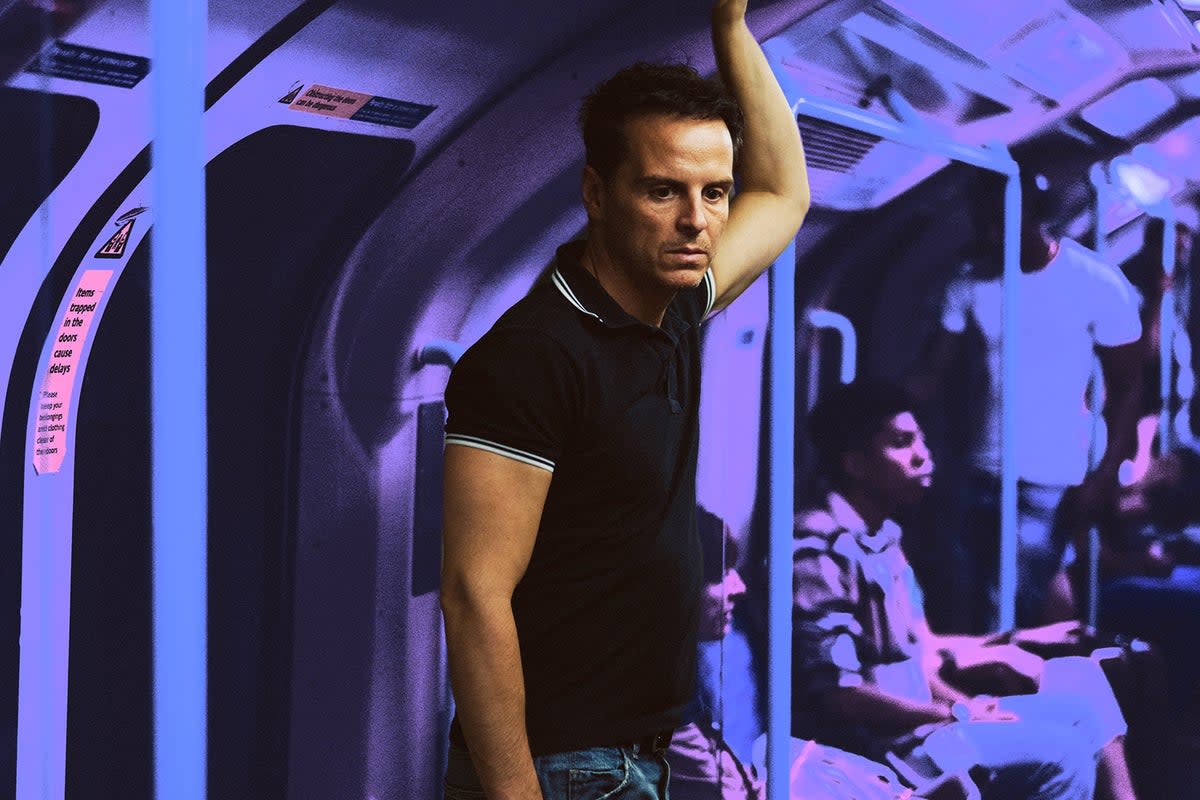

The latest artist to open up about loneliness is Andrew Haigh, the filmmaker behind quiet but penetrating dramas about intimacy – these include his breakout film about a one-night-stand less ordinary, Weekend (2011), and Lean on Pete (2017), the tale of a teenager’s search for belonging across the American frontiers.

His new film, All of Us Strangers – adapted from the Japanese novel Strangers by Taichi Yamada – marinates in a feeling that causes many of us shame, even though, in reality, it is a part of our shared experience. To take a 2023 YouGov survey of university students as an example, 43 per cent of respondents feared they would be judged if they confessed their loneliness, whereas 92 per cent had experienced it and 87 per cent said they would not judge another for expressing it.

All of Us Strangers is full of images of city loneliness. They echo the alienated neon of Edward Hopper, whose most famous artwork, Nighthawks, depicts four people appearing strikingly alone despite their fellows in an NYC diner. Haigh’s specific point of reference, however, was Francis Bacon – whose portraits possess the grotesque pain of people desperate to escape the confines of their bodies.

“Those images feel like people trapped and lost within something,” he says, speaking in a London hotel room the day after winning seven categories at the British Independent Film Awards. “There’s almost movement to a lot of his paintings, like you’re falling through space... like you’re so intensely alone that you’re not even situated in any reality.”

In the film’s reality, Adam (Andrew Scott) is a fortysomething, orphaned gay screenwriter living in an east London tower block that is deserted save for one other resident. Haigh and his director of photography Jamie Ramsay film Scott solitary against the skyline, contained by floor-to-ceiling windows, or bathed in white refrigerator light as he reaches for crusty leftovers. Haigh always knew that he wanted to set this story in a tower block, first looking in Vauxhall before deciding, for practical reasons, on Stratford.

“I wanted to try and express, almost in a phenomenological way, how loneliness feels,” Haigh says. “So he’s in this apartment block. There doesn’t seem to be anybody there. In reality, there could be people throughout, but he feels like the only person, because that’s loneliness – it doesn’t matter if there’s 10,000 or 2,000 people around; you just feel it viscerally.”

Haigh has lived in both the city and the suburbs, and thinks (like Laing) that city loneliness has an eerie quality. “Sometimes, it’s delicious,” he says. “I can enjoy walking around a city and being in my own world.”

He filled All of Us Strangers with shots of reflective surfaces. “Your reflection is superimposed on other people constantly when you’re walking around a city – when you’re standing on the Tube platform and you see people going past on the Tube and catch your reflection in the moving glass alongside the people behind on the train. Or looking through shop windows, or when a bus goes by... there’s always this separation and it has a strange effect.”

People get bullied, neglected, and pushed into the margins. We all see those things happening every day. We can all make eye contact, we can all exchange words, we can alleviate the burden for each other

Olivia Laing

Although he no longer feels blighted by loneliness – and cites a long-term relationship, with the qualifier that “you can still feel very lonely in relationships, let’s not pretend that you can’t” – what left an impression was the painful loneliness of his youth. This correlates with a 2023 Meta-Gallup survey, which found that the highest rates of loneliness are in the 19-29 age group.

“I was very lonely in my teenage years, but also into my twenties,” says Haigh, “and it sometimes felt even worse when you were in a crowd of people in a gay club. Living in London, you suddenly feel there should be so much hope. There are so many other lives, but still, you can’t seem to connect with them, and that’s almost worse than being stuck in the countryside by yourself where, at least, there’s no possibility of connection.”

The possibility of connection does, in fact, knock on Adam’s door one night in the form of the only other resident in the block, Harry. Although he seems bold – and the casting of heartthrob Paul Mescal adds to our impression of his confidence – he is even more adrift than Adam.

While the pair eventually forge a deep bond, sharing their bodies and their stories, Adam at first turns him away, neither literally nor figuratively ready to let anyone in. “I always saw Adam and Harry as these big old islands of loneliness, and sometimes the tide’s out and they can reach each other,” said Mescal at a recent Q&A for the film at London’s Curzon Mayfair.

He sees All of Us Strangers as a realistic love story. “To love someone doesn’t mean that all of your problems go away. I wish that was the case, but it’s just not. These two people are prime candidates to just disappear into the ether, and yet they keep fighting to get back in the room with each other.”

Adam and Harry are gay men who have fled heteronormative settings, only to find the silence in their intended havens deafening. The Lonely City gravitates towards queer and/or traumatised artists, too, and the most heartrending case study concerns outsider artist Henry Darger. In 1953, he experienced the death of his only friend, Willie. Darger wrote in his diary, “and since that happened I am alone, never paled [sic] with anyone since.”

There is a distinction to be made between the loneliness that arises during our transitions and losses, and the chronic marginalisation experienced by people like Darger. He – as Laing’s book details – was neglected and othered during his formative years, resulting in unprocessed trauma. Because the most alienating thing in the world is not physical solitude, but mental imprisonment. Marginalised people often have their needs ignored or misunderstood because those around them cannot (or do not want to) recognise the urgency of their situation.

Unprocessed trauma doesn’t know how to make a palatable case for itself, and can manifest in behaviours that deter potential companions. Do we have a responsibility to people languishing in this state of seemingly unbroachable loneliness?

“I really think we all do,” Laing says, “but I don’t think that’s just about befriending the lonely individual. It’s about peeling away all of the ways in which people become isolated and alienated.” Laing is speaking to me over the phone from the home she shares with her husband in Suffolk. She has – coincidentally – been looking at photos of her time in New York for a project. “One thing I was really struck by is I was so unhappy then. I could really see it in my face in a way that I might not have been able to at the time.”

Although this period feels like “a different life”, and workwise she has moved on, Laing’s connection to loneliness is constantly refreshed, for the book has connected with an intense and ever-growing fandom who reach out to her in different ways.

Her thoughts on chronic loneliness continue, fully crystallised. “With someone like Darger, there were layers of family trauma and institutionalisation,” she says. “Then it’s also about how people get bullied, neglected, and pushed into the margins. That’s a process that every single person can either participate in or refuse to participate in. We all see those things happening every day. We can all make eye contact, we can all exchange words, we can alleviate the burden for each other.”

This isn’t to let our government off the hook, though, as they’ve neglected to build lifesaving social infrastructure. Laing believes we need state-funded services, from psychotherapy and after-school clubs to access to education for adults: “All of those things that the Tories have systematically defunded for the last decade and a half of austerity,” she says. “We need different ways that allow people, if they’ve slipped through the net once, to get back into a social or creative environment, or a supportive network. Having as many opportunities as possible is vital.”

The Lonely City argues that those who suffer most violently with loneliness are not personal failures, but victims of a wider socio-political malaise. “The book [looked at] the type of experiences that people had that made them lonely, and it made me very angry,” Laing says. “I feel on the side of the lonely, really.”

All of Us Strangers is not the only new film on the side of the lonely. Sofia Coppola’s recent domestic miniature, Priscilla, features a teenage bride rolling around Graceland in silence. She is invisible, for her dream status of “Mrs Elvis Presley” negates her reality in the eyes of onlookers. In Hoard, the debut of 26-year-old filmmaker Luna Carmoon, which is due for UK release on 10 May, a teenage girl who spent her childhood with a hoarder mother fills the post-A-level void by collecting trash. At odds with her foster family, she has an affair with a man who accepts her messy compulsion.

Another debut that premiered at last year’s Venice Film Festival alongside Hoard is Moin Hussain’s Sky Peals. It was born out of lockdown isolation, and tracks a neurodivergent man working in the twilight realm of a service station. After his dad dies, he drifts away from humans and towards aliens.

When I ask Haigh if there are riches to be found in facing our loneliness, he replies by quoting Carl Jung: “Real liberation comes not from glossing over or repressing painful states of feeling, but only from experiencing them to the full.” Yet, without proof that others have inhabited this state, the prospect of confronting it can seem like tempting fate – as if it’d make us stranger still.

“I was so scared that night,” says Harry in the final act of All of Us Strangers, referring to his introduction at Adam’s door. “I just needed not to be alone.” The words catch in his throat as he does something that only the bravest artists do. He lays bare the abject force of his loneliness, warding off its alien qualities and giving it a beautiful human face. When Adam responds, it feels addressed to all of us: “You’re here with me.”

‘All of Us Strangers’ is in cinemas from 26 January