Little Richard: I Am Everything director on re-crowning the King of Rock & Roll, his sexuality, and legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It is incredibly hard, though not impossible, to overstate Little Richard's influence on rock & roll. Particularly because it has been understated or ignored or forgotten for so long. But when it comes to the pioneers, the superstars, the icons of rock & roll — Elvis, the Beatles, the Stones — they all idolized Little Richard.

He is the Originator, the Innovator, the Architect, the King of Rock & Roll. If you saw Baz Luhrmann's biopic, you'd know Elvis felt the same way, as Austin Butler's Presley lavished praise on Alton Mason's Richard.

In her new documentary Little Richard: I Am Everything, director Lisa Cortés attempts to tell the full story of Richard Wayne Penniman, a flamboyant, queer, immensely talented, and ambitious — but conflicted and at times self-destructive artist — who set the latter half of the 20th century ablaze, and burned out several times as a result. (See an exclusive clip from the film above.)

She's helped greatly by the fact that Richard told his story over and over again to anyone who'd listen. She's also hindered by a man who rejected his own self-professed homosexuality, publicly and vehemently, and who died in 2020, leaving a part of him forever unknown.

Born Dec. 5, 1932 in Macon, Ga., Penniman was loved unconditionally by his mother, but at 15 he was thrown out of the house by his father for his less-than-masculine behavior. He found a home above Ann's Tic Toc, an integrated gay bar — In Georgia. In the 1940s. (Just let that sink in for a minute.) — whose owners took him in. There, he developed his drag persona, Princess LaVonne. In 1950, he joined a band and traveled around the Chitlin' Circuit, performing in and out of drag. Again, in the South. In 1950.

"These moments are specific to Richard's evolution, but drag culture is documented going back to the 1800s, of drag balls and people who are out," Cortés tells EW. "So in a time where particularly people are looking to criminalize these performers, I think it's so refreshing that Richard's story is saying, Wait a minute, no, this community has been here for a long time. It's a part of America, like it or not."

Now Little Richard didn't just pluck rock & roll out of thin air. There were forebears whom he idolized and drew inspiration from, specifically rock pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the openly gay Billy Wright, and the flamboyant Esquerita, who taught him how to play the piano. Richard synthesized parts of these performers into his own act, creating something distinct of his own.

He recorded his first single in 1951, and its B-side "Every Hour" became a hit in Georgia, warming his father's affections to him. Impressed with his son's success, Richard's father invited him back home, only to die suddenly in 1952.

Richard continued recording throughout the '50s, honing his performance and musical style, and in 1955 he released the groundbreaking "Tutti Frutti," a song, initially, about anal sex. It was a big hit for Little Richard, but a much bigger hit for Pat Boone and Elvis Presley, who re-recorded the song, as was custom for white artists to do, for white audiences.

Cortés makes a point of drawing a distinction between inspiration and appropriation, taking influence from someone versus just plain copying them. It's this distinction that drives a lot of Little Richard's story.

But the other major driving force is his sexuality. As an effeminate, Black man from the South, wearing loud clothes and singing louder music, Little Richard was unlike anything America had seen. His very effeminacy was supposed to make him "safe" for white audiences, but his real danger lay in how this new subset of the population called the American teenager reacted and related to his music. And to him.

Black kids and white kids would break segregation laws by mingling and dancing with one another, causing the police to break up Little Richard's shows. Girls, presumably white girls included, would throw their panties onto the stage where he performed.

"I was not supposed to be the idol for their kids," Richard says in archival footage in I Am Everything, referring to white parents who objected to this confounding phenomenon known as Little Richard.

Then, in 1957, at the height of his success, Little Richard walked away from it all to become a minister. He claimed he had seen angels holding up his plane after it experienced turbulence on the way to a show in Sydney, and that after his performance there he had seen a red fireball in the sky... which just turned out to be the launching of Sputnik. Still, the deeply religious Richard Wayne Penniman took these as signs from God to repent for his "sinful" music and lifestyle.

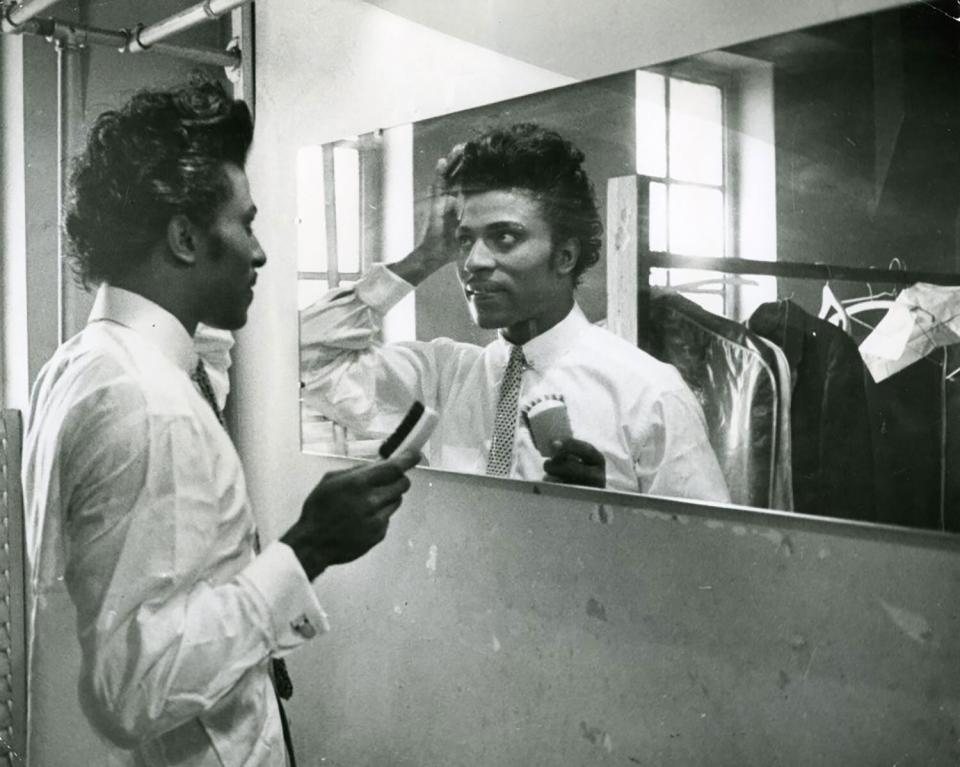

courtesy Magnolia Pictures Little Richard performing at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field on Sept. 2, 1956

He ended his recording contract early, thus relinquishing any and all future royalties to his music. For decades, Little Richard would flit in and out of popular music, at times embracing before ultimately rejecting his homosexuality, but consistently trumpeting his own significance since no one else seemed inclined to. Though he was among the inaugural class of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he missed his induction due to a car accident.

Little Richard died on May 20, 2020. At age 87, he was one of the last living elder statesmen of rock & roll. He left behind a complicated legacy, one that Cortés unpacks in Little Richard: I Am Everything. In making the documentary, premiering today in theaters and on VOD, she wanted to show him as more than just "the person who sang 'Rubber Ducky' on Sesame Street or told people to shut up."

"His contributions range from the music to the innovation in the music, to the fashion, to challenging cultural norms," she says. "And that this history is our history, and it is important for it not to be erased or for the telling of it to be kept from our children and all of us."

Here, Lisa Cortés discusses that legacy, the tricky business around discussing Little Richard's sexuality, and the impact of rock & roll — and thus Little Richard — on American culture.

courtesy Magnolia Pictures Little Richard before he performs at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field on Sept. 2, 1956

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: What did Little Richard mean to you as a child when you were growing up, how did he figure in your life, and why did you want to make this documentary?

LISA CORTÉS: Summertime. Fireflies. Roasting marshmallows. And then Little Richard comes on, and me and all the kids start jumping up and down, and twisting, and feeling this joy that I don't even know we knew what he was unleashing in us.

And so we fast forward to the spring of 2020, the pandemic has us all in lockdown, and it's a dark troubling time for many people, I know it was for me. And he passed away and I started hearing this music and it brought the joy back to me again, that joy that you feel as a six, seven year old. And I wanted to see a documentary. That's that natural thing these days, "Oh, let me see if I can watch something." And there wasn't anything to watch and that just presented an incredible opportunity, that then I found great collaborators who wanted to explore the same story.

Where did you start with your research?

A wonderful book, his autobiography, The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock and Roll. He wrote it with a gentleman named Charles White. If you haven't read it, treat yourself. It's quite spirited, and candid, and saucy, and spunky. So I started there and I then read a couple of other biographies about him, a ton of articles, a lot of watching material online.

And what became apparent to me, as a documentarian, I'm always thinking, what's a device? What's my way in? And it was apparent that Richard was the way in, that I had to give him the agency to tell his story. So in order to do that, I tasked our archival team with doing a very deep dive to see and confirm, can we find Richard narrating his cradle-to-grave story? Because that was going to be the storytelling spine to take us from his birth in 1932 to his death in 2020.

One of the craziest things about this documentary to me was just how f---ed up the '50s were, whereas it seems like Little Richard's feminine appearance made him "safer" for white audiences. What was it about the culture that made that so?

I'm equally befuddled. It's 1955, homosexuality is illegal, homophobia is rampant, and Little Richard says, "Well, because the white girls were into me, I put on a lot of makeup and I made myself more feminine to protect myself." And that's why I love the role of our Black and queer scholars in the film, who oftentimes are the audience members who are questioning Little Richard's statements.

In this case, Tavia Nyong'o is like, that does not make sense. This is counterintuitive to the learned history that we know. But I think it says something about if in the 1940s there's a place called Ann's Tic Toc where people come together, that perhaps there is a strange space that was carved out that gave him permission as long as he wasn't threatening, to at the same time be able to be enjoyed by so many different kinds of people.

courtesy Magnolia Pictures Little Richard performing at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field on Sept. 2, 1956

I think maybe the crux of the doc, at least for me, was the battle Richard had with his sexuality. Because here he was being very open in the '50s, and then he's famous for two years, and then decides to leave it all and embrace the Church and all that kind of stuff. But he still has this back and forth with his sexuality. He wants to embrace the Lord, he wants to be a gospel singer, but he still is tempted by who he is. Can you speak a bit about that struggle and how you managed to frame it?

Well, first of all, I framed it through Richard's words. He tells the story of, I'm living this high life, I think the world's coming to an end, I leave it all behind and go to Oakwood, this religious school. Wait a minute, I go to England, I'm back in rock & roll again. I was always, from the beginning of looking at his story, intrigued by this tension, by this inability for him to reconcile all that he is.

I will say in the '50s, he is out to us as we look back, but he didn't declare himself out in the '50s. You didn't do that. It's only in the '80s when he's on talk shows that he says, "Oh yes, I was gay. I was one of the first gay people." But it's an interesting thing of looking back, he can declare himself now that he no longer considers this a part of his lifestyle.

Were you able to track down any of his male lovers?

No. I searched high and low. I asked [close friends] Sir Lady Java and Lee Angel. And as close as they were to him to the end, it's that old school. I'm not saying that they knew and didn't tell me, but I think overall there's like a cone of silence. And I wonder if there is anyone who was consistently there. One of the moving points in the film for me is, he says what he really wants is love. The question comes up: if, in his inability to contain all the multitudes that he was, he ever allowed himself to have a male lover consistently.

The ascension of his success, how quickly it happened and how intense it was, maybe that played a part in his confusion or anxiety over his sexuality.

When he tells his story, he is very focused on the hits, the hits, the hits, the hits, the hits. I'm going to Australia, I see a fireball, I think the world is coming to an end, I'm giving up rock & roll. Richard gives the exterior, which is why there's the family and friends and musicians who knew him [and] are included in the film to give you a greater sense of his interiority. It's hard to know what his struggle [was] with his sexuality — how it affected the very intense rise of his success — because he doesn't really talk about it. He's old school. There's certain things that they just did not talk about.

And it goes beyond Richard. People in the community saw other queer folks and would even maybe go and get their hair done by these men, but they didn't talk about it; they looked aside.

Little Richard on 'The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour' on Oct. 1, 1971

Let's talk a bit about rock& roll in general in the '50s. It seems like such a powerful force, and it's hard to imagine what it was because we live in this time now where everything is everything all the time.

Right, right, everything's on 13.

Yeah, but rock & roll really broke through. What do you think rock & roll did as a cultural force?

I think rock & roll was this incredible catalyst, powered in part by the energy of Richard, who's a transgressive figure for cultural change. Post World War II, you have this concept of the teenager so the '50s are all about teens, and they get the keys to the car when they're 16. I like to say that Little Richard unleashed rock & roll and he freed the teenager.

And at his shows, he talks about Black kids on one night, white kids on another, then the white kids come sneaking in, then they're dancing next to one another, then the literal rope that's put up to separate them is torn down.

I think it's interesting how this music, it's not fueling civil rights — because there's certainly greater acts that are happening to empower people in the Civil Rights Movement — but it's part of, I think, how culture is quietly working to shift norms of what is accepted.

And Little Richard is definitely, for me, an intersectional character whose ability to be a touchpoint for great change — that's not just the energy of the music, the makeup, the fashion, but gender fluidity — it's the drop that starts the ripple effect.

Featuring interviews with Mick Jagger, Billy Porter, John Waters, Tom Jones, Nona Hendryx, Nile Rodgers, and others, Little Richard: I Am Everything premieres today in theaters and on VOD.

See an exclusive clip from the documentary above.

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content: