Literate Matters: McMurtry's classic promises more than it can deliver

Larry McMurtry is funny. And melancholy. He’s also insightful and hopeful. But chauvinistic too. At least in “The Last Picture Show.”

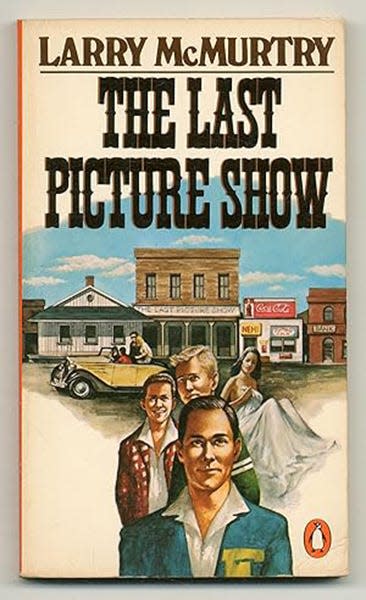

For unknown reasons, the Vintage Classic edition kept surfacing on the corner of my reading table, and since I’d somehow missed it all those years ago, I thought I should give it a try.

For those who know, and those like me who are late to the party, best pals Sonny and Duane are waiting to get out of Thalia, Texas in the late 1950s, a town where you can feel all alone or watched by everyone.

For these friends — football teammates, roommates and shadows of one another — the proximity is claustrophobic. Or liberating. Trouble brews in those moments between.

McMurtry’s Thalia is a place where the “freezing wind was just outside,” or “the afternoons were long and hot and unrelieved,” the weather punctuating the despair or the hope or — mostly — the uncertainty that plagues the boys, as well as those surrounding them.

There are love stories here, of course, but of course love is tricky. Duane pines to marry Jacy Farrow, but her parents do what they can to talk her out of it; Sonny discovers what might be love with Ruth Popper, the 40-year-old wife of his high school coach. And watching it all from her spot behind the counter of the diner is Genevieve, the aging waitress worried about her husband’s medical bills.

Others have known love too, even if it’s not theirs anymore. Sam the Lion, who owns the pool hall and the diner and the picture show once had a girl. And Lois Farrow, Jacy’s booze-soaked mother wraps herself in furs to forget what she once knew.

Coach Popper is the least likable character here, railing at his boys’ weaknesses, threatening violence if they don’t give a better effort on the gridiron or the basketball court. His stereotypical tirades and tendencies, as well as his inability to recognize how simple love could be, if only he’d talk to Ruth, helps move the story, though we’re hoping he gets his due.

There’s less empathy for Abilene or Bobby Sheen, too, men without regard for others. Their outsized egos, along with their simple assignments also help move the story, though they remain flat and eventually forgotten.

Throughout, it’s the women who suffer. McMurtry puts circumstances outside their control. They suffer more than Duane, who hopes to strike it rich so he can marry Jacy, her teenage awakening at times fascinating, but also too sensational to believe. Or Sonny, who can’t figure out what to do beyond his clandestine afternoons with the coach’s wife.

Ruth Popper suffers most, first at the detachment she endures in her marriage but then more heartbreakingly when Sonny is drawn into Jacy’s vaporous orbit. For Ruth and Sonny, their age difference might prove too great, the town too small as Ruth realizes, “it was clear that in time she was bound to be hurt, and badly so.” She yearns to stave off that hurt though with more sultry afternoons, but isn’t capable of steering her course in a more independent direction, and that’s McMurtry’s fault, not hers.

Perhaps there’s a reason I hadn’t read “The Last Picture Show” until now. Larry McMurtry is certainly funny and so much more, but in a story backlit by an emotional weight lifted, then crushed by love, unrequited or unappreciated, he owes his female characters — and his readers — more than stereotypes.

Good reading.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Literate Matters: McMurtry's classic promises more than it can deliver