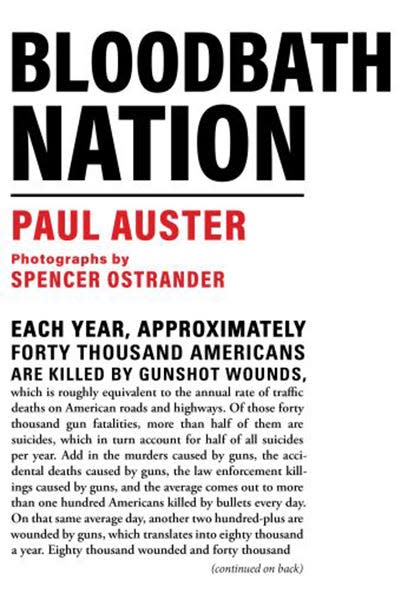

Literate Matters: Gun violence history and calamity examined in 'Bloodbath Nation'

It’s too easy to assign it to irony.

Yet on the same afternoon I was reading “Bloodbath Nation,” Paul Auster’s book-length essay on the history of gun violence in America, news broke of gunfire on the Morgan State University campus in Baltimore.

It’s as easy to assign all this to tragedy too. As Auster — as so many others have — points out, more than 100 Americans die from gunfire every day. Thankfully there were no deaths at Morgan State. But by the time you read this, 1,000 more Americans will have died by a gun.

Auster’s essay is not simply statistics, however. The most powerful part of his story is when he traces the arc of the bullet that transformed his family a century ago.

“I had two grandmothers, but only one grandfather,” he explains about his memory of growing up. Auster was always troubled, however, because when he asked about his paternal grandfather, “There was always a pause.” His grandfather either “died when he slipped off the edge (of a roof) and fell to the ground.” Or “had been killed in a hunting accident.” Or “had been killed as a soldier in World War I.”

The truth was just as final, but far more tragic. In fact Auster’s grandmother shot and killed her estranged husband in the kitchen of her Kenosha, Wisconsin home in 1919. Deemed temporarily insane, she was acquitted and the family buried both his dead grandfather and the story of what happened, though the shadow never passed.

This too is irony as well as tragedy, Auster’s interest in guns marked both by his history and our collective inability to wrestle sanity back from the proliferation of guns and the violence they wreak.

As he should, Auster references Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s compact but powerful 2018 book “Loaded,” which traces the roots of the Second Amendment, illustrating not only the racist gun-fueled origins of slave patrols, but the almost schizophrenic gyrations of the National Rifle Association. Auster’s argument doesn’t dwell here, however, shifting again to his own experiences, before detailing a litany of all too familiar names and places and numbers to illustrate the overwhelming scope of the horror wrought by guns in the hands of the wrong Americans.

As others have done, Auster uses the regulatory history of automobiles to build his case. Why, he asks, have we not followed the same course with guns?

“Cars and guns are the twin pillars of our deepest national mythology,” he believes, “for the car and the gun each represents an idea of freedom and individual empowerment.” But we heavily regulate one, while making it ever easier to acquire the other.

But while cars “are a necessity of civilian life in America,” guns are not. Guns exist for the sole purpose of destroying life, Auster asserts, largely bypassing any argument on the sport of shooting, something gun enthusiasts typically lean on more heavily than is sensible.

There is also the history of gun ownership and gun laws in America, both easily researched, but largely omitted by champions of the 2nd Amendment, who now count the U.S. Supreme Court in their corner. Guns were once heavily regulated. Gun restrictions, he reminds us, “have been part of American life since the seventeenth century, with colonial, state, and local governments passing over a thousand laws and ordinances.”

“Bloodbath Nation” is made the more haunting from the inclusion of Spencer Ostrander’s black and white photographs depicting the many mundane locations of some of America’s most horrific shootings, including the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, the Century 16 movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, and the Mandalay Bay hotel in Las Vegas. Ostrander’s photographs remind us that the violence is always close at hand.

While there is nothing fundamentally new in “Bloodbath Nation,” this does not diminish from the power of the conclusions. Indeed, we know all too well how many have died from gun violence in recent years. The question, now as before, is will we ascribe the numbers to irony. Or to tragedy.

Good reading.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Literate Matters: Gun violence history and calamity examined in 'Bloodbath Nation'