'Let's blow up this black music!': The ugliness and unrest of 1979's Disco Demolition Night

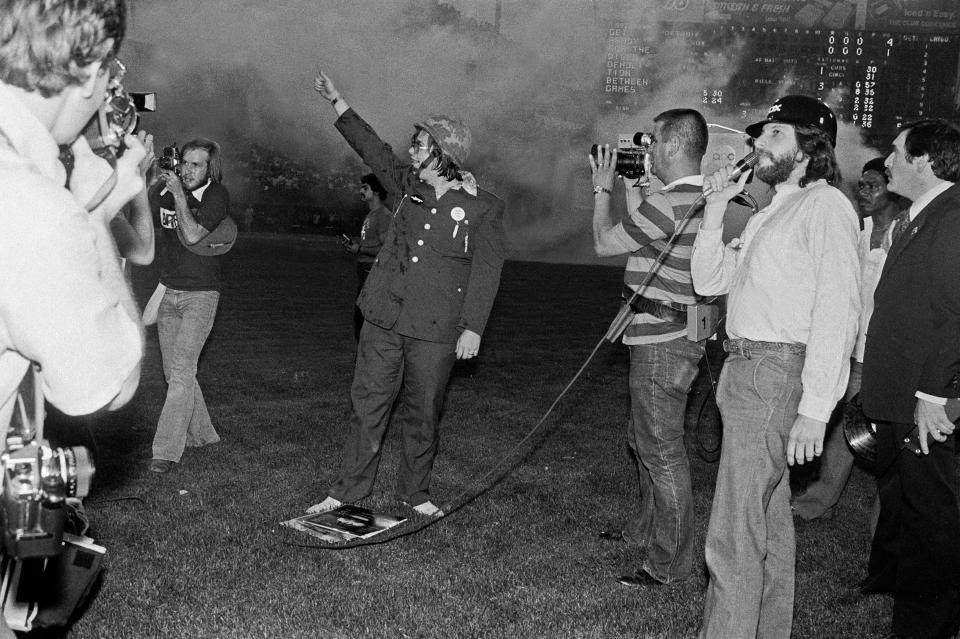

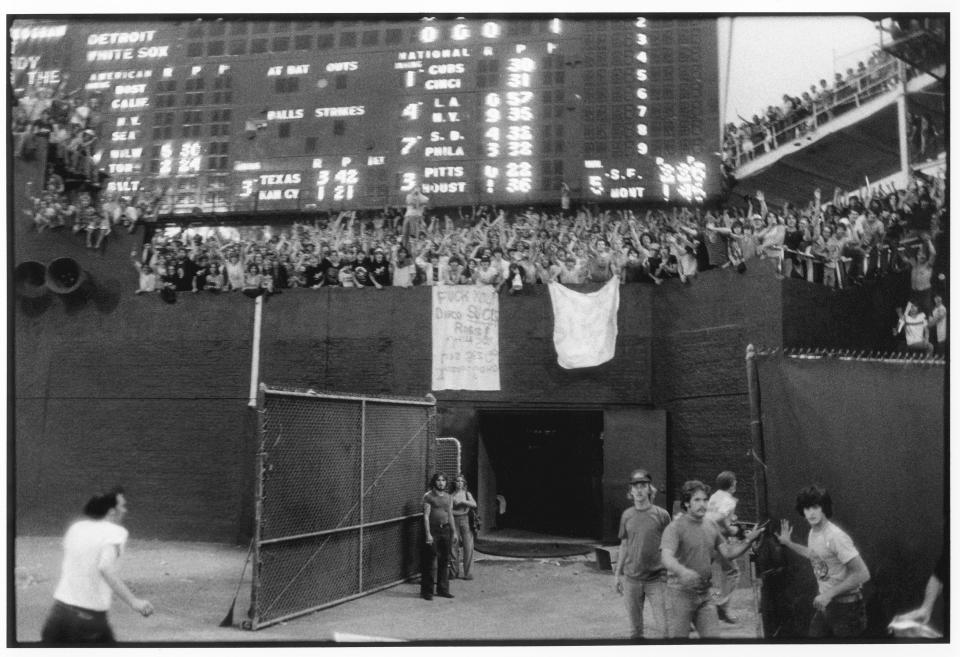

Forty years ago, on July 12, 1979, what was supposed to be a wacky promotional stunt by shock-rock DJ Steve Dahl to sell tickets to a double-header White Sox baseball game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park turned ugly — when piles of vinyl records, many by artists of color, were destroyed as thousands of anti-disco rioters, 39 of whom were eventually arrested for disorderly conduct, stormed the field. Dahl has always vehemently denied that 98.7FM WLUP’s infamous “Disco Demolition Night” had any racist or homophobic undertones or intentions, arguing that “annexing this event to today’s advocacy is lazy academically and inappropriate geographically” and that what happened should be “viewed in the 1979 lens.”

But many people claim that Dahl was, at the very least, naïve and irresponsible to stage what Chic’s Nile Rodgers once likened to a “Nazi book-burning” in the tense, segregated climate of ‘70s Chicago. Chicago house music pioneer Vince Lawrence, who was only 15 years old in 1979 and was at Comiskey Park that crazy day working as an usher to buy his first synthesizer, is one of those people.

“Steve has used the words ‘revisionist history’ countless times. I say, OK, if you want to look at this through the lens of 1979, of the time, let’s do that,” Lawrence, who is black, tells Yahoo Entertainment. “At that time, you couldn't be a black guy walking in the neighborhood of that baseball field after dark. It was widely known in the black community, and you can quote me on this: ‘Don't have your black ass caught in Bridgeport after dark.’ Young guys knew they could catch a beatdown easily that way. That’s the lens I see it through. To be occasionally called ‘n****r’ to your face was part of that culture. So to me, it's not surprising what happened.”

Dahl had recently been fired from 94.7 WDAI after that station had switched to an all-disco format, and he’d become a “Disco Sucks!” crusader at his new gig at rock station WLUP, aka “The Loop.” Dahl’s band, Teenage Radiation, had even recorded the novelty single “Do You Think I’m Disco,” a parody of Rod Stewart’s disco-crossover hit “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy.” Dahl did not respond to Yahoo Entertainment’s multiple requests to be interviewed for this article, but in a 2016 essay for Medium titled “Disco Demolition Night Was Not Racist, Not Anti-Gay” (excerpted from the book Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died, in which he exasperatedly wrote, “I’m worn out from defending myself; this event was just kids pissing on a musical genre”), he explained that his listeners “were passionate about their [rock] music and their lifestyles. I tapped into it, both as a response to being canned to make room for the disco format, and to build a community so I could keep my job.”

Lawrence describes himself as a lover of all types of music, and he says when he went to work at the ballpark that day, knowing that Dahl would be there, he hoped Teenage Radiation would be performing. He even wore a Loop T-shirt under his usher uniform. But he wasn’t a fan of Dahl’s new shtick of trashing disco records on the air.

“Steve Dahl went on a popular rock radio station at a time when rock radio in Chicago had a probably predominately white listenership. He would regularly play black music and then rip the record off the turntable with a scrape sound and add an explosion sound effect. He would do that repeatedly, in a segregated town — like, ‘Yo, let's blow up this black music!’” Lawrence recalls. “Chicago was extremely segregated, and a lot of people would say that in the ‘70s there were racist undertones, especially in certain neighborhoods, [the Comiskey Park-adjacent] Bridgeport being one of them. … So, I don't know if Steve was walking around with a bag over his head, but if he wasn't, then he had to have been cognizant of the fact that there were racist underpinnings amongst his fanbase, which were middle- and lower-middle-class white kids. I mean, you'd almost have to be walking around with your head in the sand in order to ignore that that was there.

“So, he invites all these people, saying, like, ‘Hey, if you dress or behave like that, then you're disco and you're not one of us.’ And in describing his ‘desirable’ group, he was excluding average black people, Hispanic people, even some Italians, and calling for a rally of people who weren't those people. Go figure who shows up.”

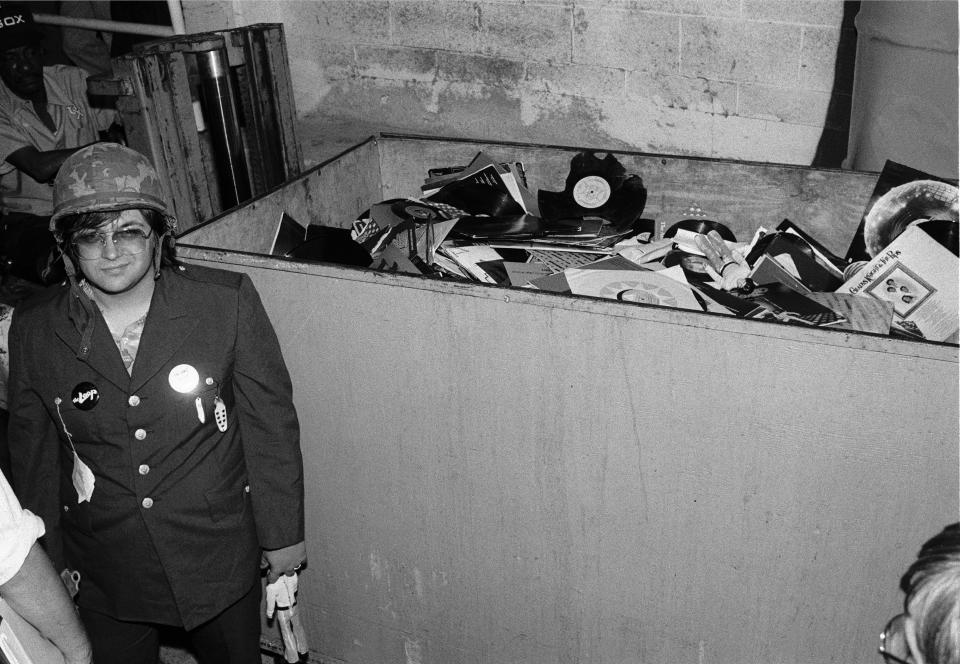

The Loop advertised that if fans brought a disco record to be detonated on the baseball field on that hot July night, they’d get in for the discounted admission of 98 cents. Fifty-thousand people turned up, which was more than three times the average attendance for a game, and 5,000 over the venue’s official capacity. It was the job of Lawrence and his fellow ushers to collect the records and put them in dumpsters by the entrance gates. That’s when Lawrence first noticed something wasn’t right.

“I was like, what the f***? People were bringing [blues/soul singer] Tyrone Davis records to this thing, and they were still getting let in for 98 cents. I mean, there were people bringing in Marvin Gaye records, Stevie Wonder records. Black records,” Lawrence recalls. “So, get this: I went to my chief usher and I bothered him, like, ‘Hey, do we have to let them in if the record is not a disco record? Because I know what disco records are.’ They said, ‘If they bring a record, let them in.’ Now, what's interesting is there were lots of ‘black disco mistakes,’ let's call them. But didn't notice any ‘white disco mistakes.’ Like, no one came in bringing a Supertramp record! So, maybe Steve Dahl wasn't actually saying, ‘Hey, just bring your black music in, we're going to blow it up,’ but it's funny how that's what happened.”

Gritty, black-and-white images captured by official photographer Paul Natkin (who declined to be interviewed by Yahoo Entertainment) do look like they were taken in a war zone. “I mean, the photographs that I've seen of Steve Dahl wearing an army jacket and helmet, holding his hands up over a pile of disco records, bear shocking resemblance to Hitler [rallies],” Lawrence says. “Wars are not always fought with guns.”

When pandemonium broke out at the ballpark, Lawrence, despite being one of the few African-American people at the scene, wasn’t afraid at first. But when rioters began taunting him with broken 12-inch records, things got tense. “People started running up on me, yelling ‘Disco sucks!’ in my face, getting in my face, confronting me as a person that ‘represents’ disco, and there were thousands of people running around in this stadium buck wild,” he says of the chaos. “I started going, ‘Wait a minute, why am I disco?’ Someone yelled at me and I opened my uniform shirt to reveal my Loop T-shirt underneath and said, ‘Look, I like the Loop!’ It was as if [my T-shirt was] my papers to prove I wasn't a Jew.”

Lawrence emerged unscathed, but he walked home that night after work brandishing his baton-like flashlight as a weapon, just in case. “I won't say that I was afraid for my safety, but I was dang sure alert and ready to defend myself, considering my circumstances of being identified as ‘disco’ out of a crowd of thousands of people.”

The disco movement had been spearheaded by many marginalized people, artists who were LGBTQ or of color, and had initially appeared to those audiences — which is why it’s so easy to assume that Disco Demolition Night had been a bigoted event. But by 1979, disco was as mainstream as a music genre could get. Saturday Night Fever was a box-office smash, with its Bee Gees-helmed soundtrack going 16 times platinum. Rod Stewart wasn’t the only classic rock artist who’d gotten in on the act: KISS, Queen, Blondie, and the Rolling Stones had also recorded disco singles. Even radio DJ Rick Dees’s goofy parody song “Disco Duck” had gone to No. 1. So, it could be argued that disco fatigue had set in after all this market saturation, and Dahl was simply in the right (or wrong) place at the right time, when music fans were eager and ready for a change. (The backlash to disco after Dahl’s stunt was immediate: Nile Rodgers told Spotify Originals, “Prior to that I never had a single that wasn't gold, platinum, double-, or triple-platinum. But we never, ever had a hit record again after that.”)

“Any rage and resistance was undirected: No ethnic group or sexual orientation was part of the equation,” Dahl insisted in his Medium essay. “It was a very different time for Chicago than it was for London or New York City. This sturdy Midwestern town was not hosting late-night clubs with red ropes. It was only rock ‘n’ roll, and that’s the way the young kids liked it. … My take was always based in humor, pointing out the discomfort of having to dress a part to go to a [discotheque]. … That evening was a declaration of independence from the tyranny of sophistication.” (Interestingly, Dahl seems to view suburban white men, not disco artists or disco clubbers, as the actual marginalized group in this scenario.)

But, as actual White Sox pitcher Richard Wortham once noted, a riot like the one that happened at Comiskey Park “wouldn’t have happened if they had Country & Western Night.” And Lawrence points out that about a decade later, when there was a swift backlash to hair metal after Nirvana and other alternative rock groups took over MTV, “There was no record-burning then, was there?”

Lawrence continues: “Time and time again throughout our country's history, they do s***ty things to marginalized people and then we fluff it up, we brush it off as innocent or say it was an isolated incident. This guy was screaming from the top of the hills, like, ‘Hey let's get together and burn all the n****r music. And a bunch of white people show up and burn all the n****r music, and then they say, ‘But that wasn't racist, it was something else.’ How many other times in America's history has some inherently, obvious, horrible, racist thing happened when they say that wasn't really racism, that was ‘something else’? Everything from the colonial-ization of America forward has been a parade of the majority inflicting its will on everybody else and under the guise of something reasonable. And that's the problem, in my opinion. So, Steve Dahl in his behavior wasn't just Steve Dahl in his behavior. It's so much bigger than Steve Dahl, honestly.”

“Revisionist history” or not, many people now view the Disco Demolition as a dark day in music history, or history in general. But most people laughed at the time. “It was evident that it was seen as OK, because the next day it was in every paper everywhere, all over the news, but the biggest complaint about the issue was not ‘Hey, why the heck is it OK to just actively destroy somebody's culture?’ That wasn't the story. The story was like, ‘Hey, the lawn on this baseball field got f***ed up,’” says Lawrence.

“The Chicago Sun-Times [wrote about how] the lawn was destroyed and ‘Oh my God, we had to forfeit a baseball game!’ In the Chicago Tribune, it was ‘Hey, someone stole first base and home plate and we had to forfeit a game. The police were called to disperse this unruly crowd who ripped up pieces of sod. Oh my God, the lawn keeper at Comiskey Park is in tears for what these kids did to his field!’ That was the popular conversation. The fact was they’d just taken a sword through black culture that was thriving, in a hateful way, but that wasn't the topic of conversation on any news channels or any of the papers. It was about the lawn. It was about baseball and ‘Shame on you young people for wrecking baseball with your party!’”

Lawrence does point out that there was one report in Rolling Stone that mentioned the inherent, if possibly unintentional, “racist and homophobic s***” that occurred at Comiskey Park. That article’s author, esteemed music critic Dave Marsh, described Disco Demolition Night as “your most paranoid fantasy about where the ethnic cleansing of the rock radio could ultimately lead… White males, 18 to 34, are the most likely to see disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks, and Latins, and therefore they’re the most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security.”

And perhaps all that so-called revisionist history hasn’t really changed how some people see this event through the supposedly woke lens of 2019. Last month, the White Sox actually commemorated the 40th anniversary of Disco Demolition Night by giving away 10,000 "Disco Demolition" T-shirts and even having Dahl himself throw out the first pitch. Many decried the event as tone-deaf: Billboard called it an “exceptionally misguided exercise,” and Vice called it “shameful” in an angry article titled “Disco Demolition Night Was a Disgrace, and Celebrating It Is Worse.” But the “celebration” went ahead as planned. “I think it's bizarre that the White Sox support this. It's not like they didn't know. I think it's all about them just not caring. Their audience thinks that's cool,” shrugs Lawrence. “I don't know. Who collects a Disco Demolition T-shirt?”

But on a more positive note, four decades later, it’s clear that disco never really died that day in Chicago; dance music just went back underground and mutated into other genres, including Chicago house. Lawrence — whose father ran Mitchbal Records and worked with Curtis Mayfield’s label Curtom Records — did eventually buy that synthesizer he wanted so badly, became a protégé of funk artist Captain Sky, and then became one of the leading innovators of the early house music scene. “It's kind of ironic that the guy who started house music was present at the ‘death of disco,’” he acknowledges with a chuckle.

As for Dahl, he seems to view Disco Demolition Night through his own rosy-colored lens. “It was a moment, quite a moment,” Dahl wrote in 2016. “I like to think of it as illustrative of the power that radio has to create community, share similarities and frustrations. It is for that magic that I wish to keep the memory severed from those who ascribe hateful motives to it.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify.

Want daily pop culture news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Entertainment & Lifestyle’s newsletter.