Let’s Take a Journey Through the Secret Queer History of Studio Ghibli Films

Studio Ghibli films take us on awe-inspiring journeys to other realms where cutesy animals and cozy vibes intersect with religion, environmentalism, and Japanese history. But this mix of child-like curiosity and mature contemplation doesn’t totally account for the studio’s sizable queer fanbase. And still, there’s something about Ghibli specifically that resonates with queer people, despite there being little obvious representation to speak of across the studio’s forty-year history.

On the face of it, much of this appeal can be chalked up to Ghibli’s fiercely strong female protagonists. Although the likes of Kaguya, Arrietty, and Nausicaä don’t actively identify as queer, gay audiences will happily follow them to hell and back. Like flying machines and delicious food porn, gay icons in this vein are woven throughout the studio’s tapestry, but only if you’re actively looking for them. Thankfully, LGBTQ+ fans are well-versed in spotting “secret” queer characters, whether they’re intentionally coded as such or not.

More from IndieWire

Take Ursula in “Kiki’s Delivery Service”: When Kiki meets this bohemian artist, she’s down on her luck, struggling to find her place in the big city. But Ursula, a kindred spirit, makes Kiki feel better by reminding the young witch of her true potential. Not long after, Kiki encounters two older women living together (eyebrows raise) who demonstrate what love and acceptance can look like for her in the future. Combined, these two scenes suggest what could be interpreted as a sapphic journey that helps Kiki embrace what makes her different, and even feel empowered by it.

While the likes of Ursula only appear briefly on screen, Ghibli actually features another notable gay icon who technically doesn’t appear at all. Moro, the Wolf Goddess of “Princess Mononoke,” was voiced in Japan by Akihiro Miwa, a legendary drag queen who publicly came out in the 1960s. Knowing that this powerful mother figure is voiced by a queer pioneer makes the film’s focus on chosen family that much more poignant. Like Kiki, the titular Princess doesn’t fit into regular society, happily living instead with the wolves who raised her. It should go without saying that outsider experiences like these are synonymous with queer identity, something that Ghibli’s historically mined plenty of tension from.

Enter Chihiro, the protagonist of “Spirited Away,” who winds up alone in an otherworldly bathhouse. Eventually, various spirits help Chihiro adjust and even thrive in this strange new place, reminding us that community can literally be life-saving for people who are perceived as “different.” What might also ring true for some LGBTQ+ fans is how Chihiro’s parents try to dismiss her experiences beforehand, gaslighting her into thinking that what she knows to be true is somehow false or less important.

Hayao Miyazaki’s follow-up, “Howl’s Moving Castle,” puts even further emphasis on chosen family when Sophie moves in with a bunch of misfits. Calcifer and Markl welcome her first, and then Sophie passes that goodwill on by looking after The Witch of the Waste, a fabulous, narcissistic creation who’s consumed by jealousy and even huffs what suspiciously looks like poppers at one point. (We have no choice but to stan.)

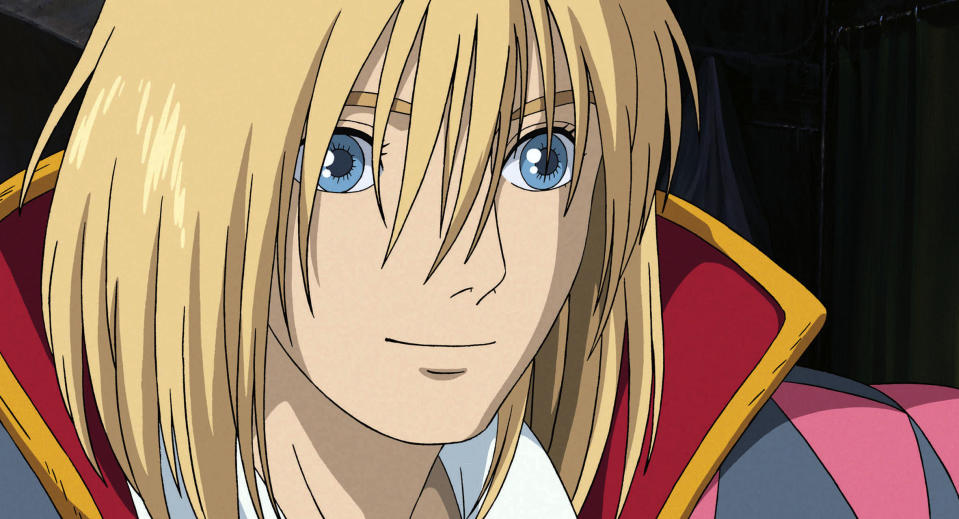

And what of the The Hottest Man in Ghibli™? With or without his dangly earrings, entire manuscripts could be dedicated to Howl’s chaotic bisexual energy. The magic fashionista will happily fill a whole room with disgusting black sludge just to make a point, the point being don’t mess with his hair products.

Still, the family you choose will always stick together, no matter what you might pull, and that’s an especially important message for queer people coming into their own. Throw in fantasy themes with literal transformations and each world that Ghibli creates suddenly becomes fertile land for queering the status quo by venturing into strange new worlds that speak to our understanding of “otherness” that we ourselves embody.

“Howl’s Moving Castle” physically takes us to different realms through a shifting doorway while other films like “My Neighbour Totoro” instead blur the lines of this liminal space, peeling back the layers of “normalcy” to reveal a world of magic lying in wait, just below the surface. To be queer is to let go of what the world tells you to think and to start believing in how you feel inside, which can lead to outer changes as well.

In that regard, Ghibli also appeals deeply to queer notions around gender, be it Nausicaä’s androgyny, the shifting physicality of the “Pom Poko” raccoons, or Porco Rosso (whose exterior doesn’t match who he knows himself to be on the inside).

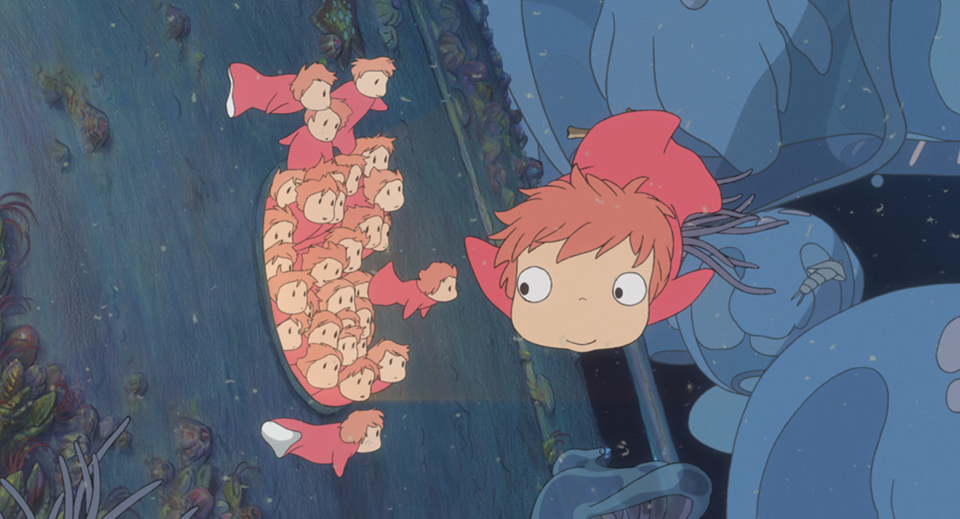

“Ponyo” might be the best example of this particular trans allegory, however. The “Little Mermaid”-esque protagonist of Miyazaki’s eighth Ghibli film longs to become human, and when Ponyo takes that desire into her own fins, it’s empowering for her and us alike to see body and soul align with such abundantly queer joy. At one point, Ponyo even gets into a fight with her father over changing her name, but once again, it’s chosen family who step in to validate her identity.

Yet it’s important to note that Ghibli doesn’t always get it right, not even when it comes to implied LGBTQ+ representation. In “Tales from Earthsea,” Cob isn’t a “villain” in the traditional Ghibli sense, which is to say that he’s an actual villain rather than the kind of nuanced antagonists fans are used to seeing. It’s unfortunate then that one of Ghibli’s very few unquestionably evil roles is also one of their only transfeminine characters. While we’re now approaching a point in which villains can be queer without feeding into stereotypes, Cob’s physical characteristics seem to be trans-coded as a shorthand for evil rather than stemming from a desire to explore gender identity.

However, even that misstep pales in comparison to the end of “When Marnie Was There.” For casual viewers, it’s just an emotional, coming-of-age story, but to queer audiences, something gay is afoot. Depressed teen protagonist? Check. A new intimate friendship made in hot girl summer? Check. Cute gay picnics and longing gay glances? Check, check, check. But then, just as you think Anna and Marnie are going to become Ghibli’s first same-sex couple, it’s revealed that Marnie is actually Anna’s grandma. Yes, really. It’s enough to make you never trust people again.

Yet, despite that unfortunate turn, the gay vibes are undeniable up until that point; if you just switch the film off before it ends, you could argue this is the closest Ghibli has ever come to crafting a LGBTQ+ love story. Well, unless you count a little-seen experiment from 1993 entitled “Ocean Waves.”

This modest drama revolves around a love triangle between two best friends, Taku and Yutaka, who compete for the affection of a girl named Rikako. Except, they actually seem far more interested in each other. Lines like “I just wanted to see you” and “I always thought of Yutaka a bit different than my other friends,” make “Ocean Waves” gay in all but name. That is until a decidedly heterosexual ending suddenly undoes all that queer subtext.

It’s unfortunate that Ghibli’s “accidental” gay movie is the closest the studio has ever come to giving us tangible LGBTQ+ representation. Because, as much fun as it can be to look for queer subtext and make gay icons out of already iconic characters, Ghibli’s LGBTQ+ fanbase also deserves actual queer characters who can unapologetically be themselves.

Yet the release of “The Boy and the Heron” does feel like a turning point. Sure, Miyazaki’s latest masterpiece isn’t remotely queer, but with his umpteenth retirement pending, it truly feels like Ghibli is at a crossroads, which means there’s more opportunity than ever to redefine what the studio looks like (and what it can portray) moving forward.

Until that day comes, LGBTQ+ fans will just continue to queer Ghibli for themselves and find comfort in these gorgeous fantasy worlds where misfits belong and outsiders find purpose. Even without any actual queer characters to speak of, Ghibli films and their expansive cast of characters represent a kind of chosen family for us, one which we can escape to over and over again, no matter how hard life gets in the real world.

Best of IndieWire

2023 Movies Shot on Film: From 'Oppenheimer' to 'Killers of the Flower Moon' and 'Maestro'

Quentin Tarantino's Favorite Movies: 59 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.