Leslie Jamison got married, had a baby, got divorced – then wrote a book about it all

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

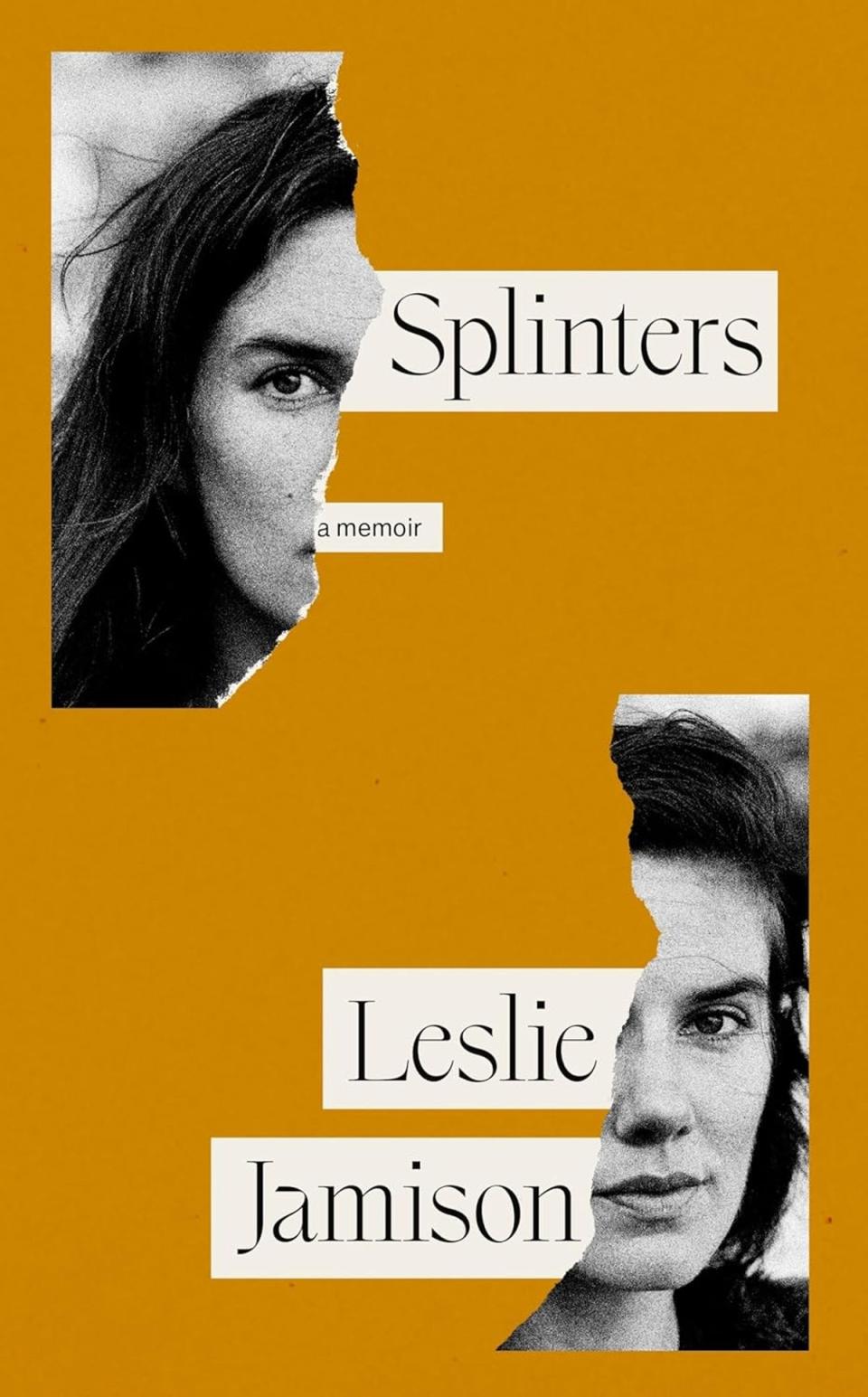

Call Leslie Jamison a narcissist and she’ll shrug. “It’s a word that often gets thrown against memoirists like me,” says the New York Times bestselling author. “The rise of the memoir is often taken as a sign of our ‘narcissistic’ times.” These days, she jokes, every bad boyfriend is dismissed with the diagnosis. But, unfortunately, so is a woman who puts the intimate details of her personal life in the public domain: Jamison’s work has dived deeply into her struggles with anorexia and alcoholism. In her new memoir, Splinters, she unpacks her decision to leave her husband in 2019 when their baby was just 13 months old.

Snatching time for a video link interview between teaching classes at Columbia University, perky, perceptive Jamison tells me she’s keenly aware that a divorce memoir might come off as a writer’s attempt to turn her side of things “into some kind of official account”. But those familiar with the work of a woman widely hailed as the Joan Didion of her generation will know better than to expect narcissistic self-justification.

Jamison, 40, is relentlessly challenged – by friends, family, strangers and her own self-doubt – over her choices. Her choice to walk away from a difficult (but not violent) relationship and become a single parent. Her choice to keep working. Her choice to throw herself into a reckless new romance. And, of course, her choice to put the whole thing on the page.

Instead of lamenting the self-absorption of 21st-century memoirists, Jamison thinks we should marvel at “how interested modern readers are in the lives of others! At how we’re all looking for these points of connection, into these lines where other people have nailed down or distilled thoughts and feelings that may have been more nebulous, less understood by us until we saw them on the page.”

In other words, it’s wise to be nosy. Because you’ll find that no matter how weird or unusual you imagine your own impulses to be, others will have felt the same stabbing shame of theirs. This idea is built into the title of Jamison’s book, which she tells me was written in short splintery passages designed to “feel painfully lodged under the skin”. It’s a condensed record of angry texts, unsettling conversations and single-parent guilt. Although Jamison holds back some details (including names) to protect others from becoming characters in her story, she’s frank about herself and her post-divorce yearning for a romance with a singer/songwriter who, she writes, “f***ed me in ways I’ve never been f***ed before”, but had no interest in fidelity or child-rearing.

This transient lover’s breezy attitude to life offered a contrast to that of Jamison’s ex-husband, the novelist Charles Bock (referred to as “C” in her book) whose angry outbursts she came to feel looming “like a pressure drop before a storm. It was almost a relief when the rain came.”

Although Jamison describes the stress of the hypervigilance this caused, she’s clear that Bock is an interesting, charismatic and – in some contexts – loving man and caring father. One of the sharpest paragraphs in the book finds Jamison’s decision to leave such a man challenged by a female taxi driver who makes her decision to leave him sound like privilege, when so many violently abused women are forced to stay.

“One of the writing rules I try to live by is making sure other people have some of the best lines,” she tells me. “So rather than staging elaborate dramas of inner debate, I look out for moments of encounter where I can be usefully challenged or thrust up against something.”

In those moments, Jamison uses a personal story like a canary in her culture’s mineshaft. The late Didion used her experiences the same way. But Jamison doesn’t relate to “the chill” she feels in Didion’s voice (honed in homage to male writers like Hemingway). Her own tone is more warmly and messily relatable on the page. Google Jamison’s recent essay on daydreaming to see how quickly you get sucked into her confessions of building fantasy lives with men she’s only briefly met, and you’ll feel she’s like a bestie injected with truth serum.

What Didion and Jamison do have in common is an instinct to identify shame as a smoke signal for a subject that demands attention. “Shame,” Jamison says, “usually comes from some part of yourself that you’re trying to disown. So, what if you allow that that part of yourself is here? Ask what has it done? And what can you make of it?”

Splinters finds Jamison – the daughter of nutritionist Joanne Leslie and economist Jean Jamison – exhuming many shames past. She describes how her mother left her adulterous father when she was aged seven or eight, after 22 years together. In one tender passage she writes that she thought of herself as a “‘child of divorce”, as if divorce were a parent. “When I was very young I thought divorce involved a ceremony: the couple moved backwards through the choreography of their wedding, starting at the altar; unclasping their hands, and then walking down the aisle. I once asked a friend of my parents: ‘Did you have a nice divorce?’”

After splitting from Bock, Jamison found herself feeling “as if I were shifting back and forth between the spectral bodies of my parents. Most of the time I was my mother, the bedrock of our baby’s life; but two nights a week I was my father, or how I’d come to imagine him, untethered, able to stay out late, or throw myself into work. It felt like cheating. It also felt good. Expansive. Intoxicating. Free.”

Having read Jamison’s book on alcoholism, I wonder if she feels the release-shame-acceptance rush of confessional writing satiates the same hunger. She laughs. She’s been sober since 2010 though writes of an ongoing desire for the “rush of relief” alcohol gave her. She admits to sating some of that validating relief with “sales, clicks and likes” but laments that the quick release of booze cannot be matched by the very slow process of her work. It took her five years to write this book.

Shame usually comes from some part of yourself that you’re trying to disown

Her addictive self, she suspects, is more likely to have migrated to online dating where she reunites with “the same part of me, that is thirsty for approval and afraid of rejection. Swiping and swiping and it’s never enough, I can become a bucket with a hole in the bottom.”

She’ll be the same reading the press around this new book. Interviews she gave for her last book The Recovering (2018) painted such an Insta-perfect picture of her post-alcohol life as a wife and new mother. That annoyed her, although she was complicit. “I deliberately chose to keep my marriage, my motherhood out of that book,” she says, “I didn’t want my sobriety tied into the old-fashioned sexism of the marriage arc.” In Splinters, she describes the stress behind one of those interviews – a new mother strapped into a designer gown, a couple already in counselling presented as a doting ideal.

I must admit I googled those interviews and then spent over an hour online trying to identify her “tumbleweed” lover. She’s not surprised. It’s an instinct she shares. In her daydreaming essay she admitted that while “one person might say ‘Google stalk’ and mean glancing at a Wikipedia page, to me it means getting to the bottom of the fourth page of search results, or the ninth, to the article someone’s mother once published in a neighbourhood newspaper recounting her childhood vacations to an island off the coast of Maine.”

Because I’m also a single mother – recently accused of “gaslighting” my teenage kids by remembering their early childhoods as happier than they were – I ask Jamison if she worries how her daughter will respond to this account of her infancy. Jamison perks up. “Gaslighting? Oh! I’m just working on a piece about gaslighting for The New Yorker!” She’s boiled this down to how we express our reality without denying that of others. But she suspects that many people who feel “gaslit” may need to rethink a victimhood based on “the pain of somebody else’s version of reality being different to yours”.

Everybody causes harm. You just have to figure out what harm you’re going to cause, why it matters and whether you can own it

But she concedes that it’s likely all parents gaslight their children with beach photos and adorable anecdotes that conceal the layers of conflict and boredom. “Yeah. I notice myself doing this,” she nods. “I catch myself wanting everything to be OK for my daughter, so I hear myself saying things are OK when she’s upset.” As a woman who spends her working days teaching aspiring writers to identify the precise truth of their feelings, she is aware it’s ironic that “I’m using my leverage to say: no, you’re not upset.”

She hopes her daughter reads the book one day. “Splinters is a kind of a love letter to her: a version of the first years of her life that holds a tremendous amount of love and beauty rather than a sorrowful origin story.” Jamison tells me that now her child is in kindergarten she’s becoming aware that she’s unusual in shunting between households. “But I doubt that she’ll feel alone with that as she moves through school. More and more kids will experience the same.” Jamison looks down into her lap, collecting her shame and her hope.

“A friend told me something really useful, once,” she says. “I was talking to her about ‘doing harm’ and instead of saying: ‘Don’t worry, you won’t cause harm’, she said: ‘Of course you’ll cause harm. Everybody causes harm. You just have to figure out what harm you’re going to cause, why it matters and whether you can own it.’” Jamison smiles softly and takes on a tone I imagine she uses with her students. “There is no perfect life where one does no damage, like pack it up backpacking leaving no trace behind. We are all leaving our detritus. We are all leaving a mess, grieving the lives we didn’t live and owning the harm we did.” She tilts her head again. “You can live a good life anyway and that’s where I hope this book lands.”

‘Splinters’ is published by Granta on 22 February