Leonard Cohen Biographer Sylvie Simmons Shares Her Thoughts on His Passing

By Sylvie Simmons

This is a hard piece to write. I’ve been putting it off for the last nine days, since Nov. 10, when my phone started to ring off the hook. On one line was the Washington Post, on the other the Canadian News agency, asking if I could confirm that Leonard Cohen was dead. There had been a post on Cohen’s Facebook page, one of them was saying, but it could have been hacked, and who believes Facebook anymore? I felt like I had been drained of air.

While listening to the talk I messaged a close friend of Cohen’s. Yes, he said, Leonard died on Monday, three days before. I knew that, in spite of his celebrity, Leonard was a very private man. It made sense that the announcement would come only after a very private burial. At that point someone called from NPR and I was on the air, trying badly to answer some question or other that echoed in the emptiness I felt. The media circus has been keeping me busy ever since.

What kept going through my mind was that only five weeks before we had been in touch. Leonard’s email was short, but his emails always were short — and elegant, concise, and gracious, often as not humorous, or if circumstance dictated otherwise, wise and kind. In that last email he mentioned that he was “a little under the weather.” I’d taken him at his word, forgetting what a master of understatement he was. When he had found out, at the age of 70, that he had been bilked of his life’s savings by a former manager and he was broke, his response was that it “put a dent in [my] mood.”

I suppose this might be good time to tell you that I am (it will take some time to get used to the past tense) Leonard Cohen’s biographer. I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (2012) had his support and assistance. What it didn’t have was interference. Leonard’s one and only requirement of me was that I whitewashed nothing. He did not want a “hagiography,” he said. That in itself should tell you something about the man. He would have been the last person to claim that he was without flaws. This had nothing to do with his innate modesty and self-deprecation. Imperfection, the state of being cracked or broken, was one of his deepest studies and might have been his battle cry. As he sang in “Anthem,” “There is a crack in everything/ That’s how the light gets in.” Despite his reputation for darkness, he was all about finding the light. He knew darkness, certainly, having fought clinical depression for much of his adult life. But he looked darkness in the eye and took from it a poem or a painting or a song. Or a laugh. Leonard had a fabulous sense of humor, most of it black.

But back to Leonard wanting the truth told in his biography: Honesty was of prime importance to him. Honesty and its near-twin, authenticity. You might have heard about how songs were often torn from Leonard. How it took him 10 or 15 years to write “Anthem,” for example. He actually recorded it on three different albums, the last being The Future, rejecting it the first two times because when he listened he felt that the guy singing was putting us on. It took him more than five years to write his all-purpose hymn for the 21st century, “Hallelujah,” which is either about the bleakness of human relations or a feelgood song, and — the Lord works in mysterious ways — a favorite vocal workout for aspiring American Idols. The problem, Leonard said, was not with writing a song. He could do that relatively easily. It was this craving for complete authenticity. He didn’t come to fool ya. Leonard was never one who took us and our attention or affection for granted.

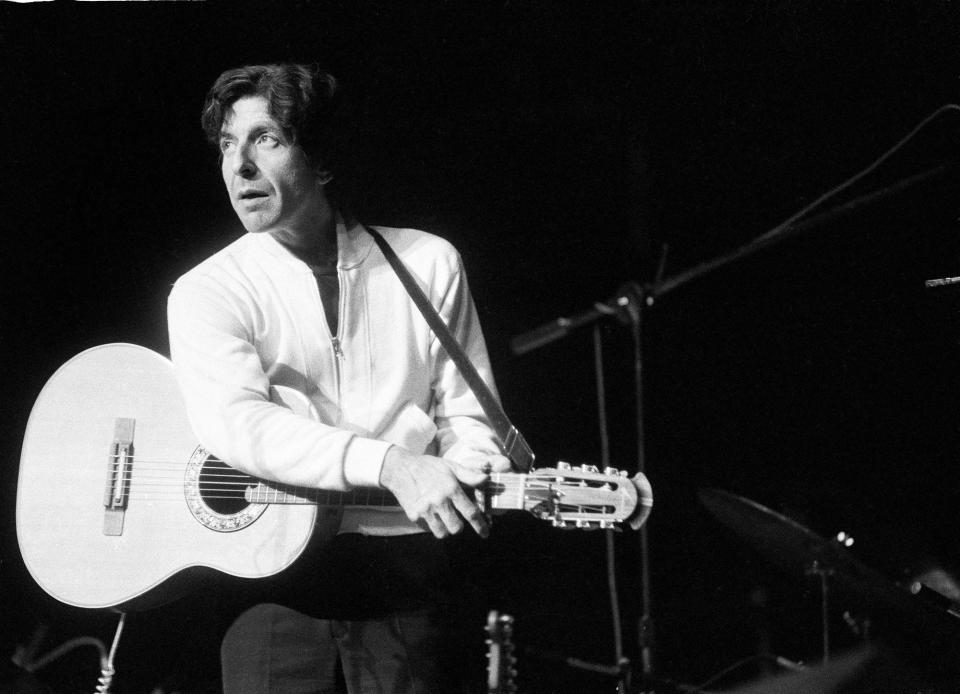

All these interviews I’ve been doing these past few days would ask who he was, what was the significance of his death. Some wanted a grand statement, some wanted to know if he, not Bob Dylan, should have gotten the Nobel prize for literature, and some wanted potted histories. He was born and raised in Montreal, a Jew whose family were rabbis and founded synagogues, or businessmen and founded Jewish newspapers — good people, serious people. Leonard became a serious poet. His first collection, Let Us Compare Mythologies, was published in 1956, more than a decade before his first album Songs of Leonard Cohen was released. He was already in his thirties by then. I heard that album when I was a young girl. I remember thinking that his photo on the album sleeve looked like a dead Spanish poet. Leonard had been raised on the English and Irish poets before falling for the dead Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. Leonard was 15 at the time; the same age he was when he got his first guitar. He decided to try his hand at the music business because he couldn’t pay the grocery bills with poetry. And, he said, there had always been music behind every word he wrote.

Leonard had been living in a little white house on the Greek island of Hydra. He moved to New York to live in a hotel. Then he found a little house in an unglamorous part of Los Angeles, because that’s where his close friend and Zen teacher Roshi (Kyozan Joshu Sasaki) set up his first Zen Center in a garage. Leonard moved again to be near Roshi after releasing and touring with his two U.S best-selling albums, I’m Your Man and The Future. For five and a half years Leonard lived in a little hut on Mount Baldy, above the snowline, and was ordained a Buddhist monk. He remained a Jew. When he came down from the mountain he chose not to return to the music business, releasing a very occasional album instead and staying off the road. Until that business with the money forced him to shine his shoes, brush himself down, and tread the boards again for the first time in 15 years. It was the most remarkable comeback tour in popular music history. Leonard learned to love the road, the discipline, companionship–and, as he put it, feeling of full employment. He loved being of service and doing his work.

When he stopped touring, he worked nonstop at his home studio in L.A., releasing three new studio albums in five years — a miracle from someone never known for prolificacy. In his last album, the masterpiece You Want It Darker, he sang himself home to Montreal. On the title track, instead of the women singers who so often accompanied him, it was the cantor and choir of the synagogue that his great-grandfather had founded and where Leonard’s name was written in the Registry of Births in 1934. He was buried in its cemetery, in a plain pine coffin, next to his family, on that Thursday afternoon that I found out that he was gone.

Eighty-two is a good age. Leonard was ready to go. But the timing couldn’t have been much worse. The same week as the election, whose result was a terrible blow to many artists, poets, and musicians. And all who love music have been reeling from an unparalleled year of death and mourning for the cultural icons we have lost. Like David Bowie, who also left us with a deep and brilliant album, Cohen was a one-off, monumental, a major influence, irreplaceable.

But Leonard faced death head-on, the same he had always faced darkness. They seemed to have come to some kind of amicable-enough agreement decades before. He had come to terms with growing old, too. “I think it’s one of the most compassionate ways of saying goodbye that the cosmos could devise,” he said. And age suited him. The Rat Pack rabbi that skipped onstage and fell to his knees in those extraordinary concerts looked more at home with himself than the young Leonard ever had.

When I last visited Leonard at home, he was working. “Time speeds up the closer it gets to the end of the reel,” he explained. “You don’t feel like wasting time.” In his last days, I hear that he was working on a collection of poems and that he had completed at least one new song. He died with his boots on. And he has left us with so much.