Legend of the Croisette: How Ken Loach Conquered Cannes

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The 1970 edition of the Cannes Film Festival was noted for giving rise to several bold new voices. Robert Altman arrived as an established (and notoriously troublesome) TV director but left a Palme d’Or winner with M*A*S*H, his launchpad to becoming one of the most pivotal figures of contemporary cinema. In the Directors’ Fortnight competition, then a year old, the German absurdist comedy Even Dwarfs Started Small gave audiences a hint of what a 20-something festival first-timer named Werner Herzog might have up his creative sleeve.

Over in the Critics’ Week sidebar, a rising English director named Ken Loach also was making his Cannes debut (like Herzog with his second feature).

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Cannes: Austrian Production Company Schubert Launches With Projects From Past Fest Contenders

Cannes: New Zealand Historical Maori Action Drama 'Ka Whawhai Tonu' Unveiled (Exclusive)

Cannes: Plus M Entertainment CEO on Turning the Family Firm Into a Korean Content Powerhouse

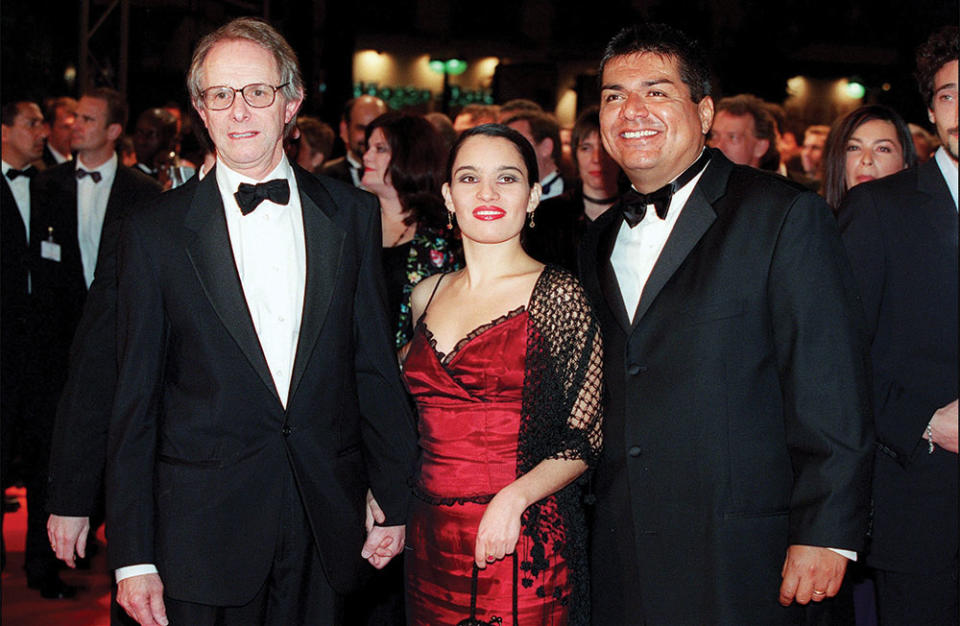

The bespectacled 33-year-old had arrived as part of what he describes as a “rather snooty” U.K. delegation that didn’t have much time for someone then known for hard-hitting TV docudramas and not considered part of the “old-established British film industry.” But in Cannes, Loach enjoyed a “wonderful reception” from a crowd of like-minded filmmakers who were all “passionate about their work.”

His sophomore feature, Kes — about a working-class boy whose adoption of a young falcon brings respite from a troubled life both at home and in school — had received its world premiere two months earlier in the northern English industrial town of Doncaster, somewhere “not noted for its film premieres,” Loach says, and was, very slowly, gathering steam via word-of-mouth around the U.K. But the screening in the South of France would put the film — and its director — on the world map for the first time, providing a vital early boost on a remarkable trajectory.

“Cannes was very important,” Loach tells The Hollywood Reporter. “But Cannes has always been important.”

More than 50 years after its bow on the Croisette, Kes is regarded as an all-time classic, a hugely influential work that the British Film Institute ranked seventh on its list of the best British films of the 20th century.

Loach, now 86, may still be considered somewhat of an outsider in the U.K. industry, but he’s a filmmaker who needs zero introduction, regarded as one of Britain’s most important directors, one whose name has become an adjective for a particular brand of kitchen-sink cinema. He’s also preparing for what is likely to be his final trip to Cannes, bringing an end to what is arguably the most successful run by any director in the festival’s 76-year history.

The 16 films Loach has launched in Cannes since Kes have won him a record-tying two Palme d’Ors (for 2006’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley and 2016’s I, Daniel Blake), three jury prizes (Hidden Agenda in 1990, Raining Stones in 1993 and The Angels’ Share in 2012), three FIPRESCI trophies (Black Jack in 1979, Riff-Raff in 1991 and Land and Freedom in 1995), plus a couple of Ecumenical Jury honors (Land and Freedom and 2009’s Looking for Eric).

The Old Oak — which he says is “realistically” his final feature, pointing to his advanced years — will be his 18th film at the festival and his 15th in the main competition, something no other filmmaker has come close to achieving.

While Loach may have won admiration worldwide for his thoughtful, compassionate and politically fueled social realism (and a commitment to left-wing principles that has added an at-times divisive element to his work), Cannes is a festival where he is, quite simply, adored. Not that he takes any of it for granted or even thinks any sort of special relationship exists.

“I wouldn’t allow myself to think that, because you’ve got to do it each time — we certainly didn’t take this year’s invitation for granted,” he says, asserting that the possibility of a Cannes launch is not even mentioned while he’s in production. “It’s like a football team and not wanting to talk about promotion. You just hope that they see something in the film that they want to show.”

And Cannes’ programmers have repeatedly seen something in Loach’s films, be it a vivid character study of a recovering alcoholic (1998’s My Name Is Joe), a drug-soaked and heartbreaking portrait of juvenile delinquency (2002’s Sweet Sixteen), an uncompromising examination of Irish independence (The Wind That Shakes the Barley), an angry dive into the exploitative world of private military companies (2010’s Route Irish) or a searing takedown of the cruelty in Britain’s welfare system (I, Daniel Blake).

There’s a near-farcical contrast between Loach’s films that have shown inside Cannes’ various cinemas and screening rooms and the ostentatious glitz and gratuitous wealth paraded outside — or, as he puts it, “the showoffs with the big boats.” For the record, he says he hasn’t once set foot on a yacht in all his time there. And when he won his first Palme in 2006, did he celebrate with a champagne reception in a hotel suite? In classic Loach style, it was — of course — with a cup of tea.

For Loach, the real impact of Cannes is its “powerful” audiences and the platform it gives him to present — and discuss, with journalists from all over the world — the thoughts and frustrations about injustice and opportunities for change presented in his films. “If there are ideas you want to communicate, it’s the best way to do it,” he says.

Loach’s second Palme d’Or winner, I, Daniel Blake, is a prime example of this. The reaction in Cannes — which included a 15-minute, teary-eyed standing ovation — was the initial spark that lit the fuse under the film. It went on to become a rallying cry for social justice around the world (“Moi, Daniel Blake” read a banner at a demonstration protesting austerity in France), and its subject is still discussed to this day. Spurred on by Cannes, the feature also gave Loach his biggest opening in the U.K., and with $15.8 million at the box office, is one of his most successful titles, second only to The Wind That Shakes the Barley.

But it hasn’t all been about extended applause in the Palais (which he says wasn’t even there when he first came to Cannes). During a period of noted inactivity in the 1980s, when he claims he “couldn’t direct traffic,” Loach recalls staying in one of the town’s cheapest hotels with a producer as they tried to find funding. “And we failed dismally — we didn’t get to see any films, we didn’t get any invites and ran out of money and had to borrow some to get to the airport.”

The hot Cannes streak began when Loach started collaborating with producer Rebecca O’Brien (beginning with 1990’s Hidden Agenda) and was further cemented when they teamed with screenwriter Paul Laverty, whose first trip to Cannes was in 1998 with My Name Is Joe.

The Old Oak — Loach’s 16th feature with O’Brien and 14th with Laverty — finds them in familiar territory. Blending old issues with new, the drama centers on the last remaining pub in a former mining town that has fallen on hard times and where dirt-cheap housing makes it the ideal location for authorities to ship Syrian refugees, plunging them into a divided community looking to find someone to blame for years of isolation and neglect. “It’s a very good Loach,” notes one insider.

Laverty — for whom The Old Oak marks his 11th visit to Cannes with the director — acknowledges the “genuine affection” for his friend among fellow attendees. “You see people just stopping him, taking his hand and saying thank you,” he says.

However The Old Oak is received in the South of France, it’ll give Loach and his band of regulars — O’Brien and Laverty, plus editor Jonathan Morris (who has worked with Loach since Hidden Agenda), stills photographer Joss Barratt (since 1996’s Carla’s Song), cinematographer Robbie Ryan (since 2012’s The Angels’ Share) and sound recordist Ray Beckett, production designer Fergus Clegg and script supervisor Susanna Lenton (all since 1993’s Raining Stones) — one last chance to come together and celebrate all that they’ve achieved over the years. Hot beverages may be involved.

Of course, Loach has famously retired before. 2014’s Jimmy’s Hall was supposed to be his last feature, but the election of the Conservative Party in the U.K. the following year dragged him angrily back behind the camera to make Daniel Blake. Given the current state of politics at home and abroad, is he really ready to pack it in?

“When you’re getting on, you’re in the lap of the gods, really, so just cross your fingers that you’re not in the obituary column,” jokes Loach. “But who knows.”

***

Prince of the Palais

KES

A 33-year-old Loach made his Cannes debut in 1970 (in Critics’ Week) with this career-defining drama.

MY NAME IS JOE

Peter Mullan received Cannes’ best actor award in 1998 for his portrayal of a recovering alcoholic.

THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY

Loach won his first Palme d’Or in 2006 with this war drama about Irish independence.

LOOKING FOR ERIC

Cannes enjoyed a rare splash of humor from Loach in 2009 (and gave him the top Ecumenical Jury honor).

I, DANIEL BLAKE

His record-tying second Palme d’Or came in 2016.

THE OLD OAK

Loach’s 18th film in Cannes is his 15th in competition and — if he’s to be believed — his final feature.

This story first appeared in the May 10 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Natalie Portman at Cannes: "I Need to Leave the Drama for the Screen"

Ailing ‘Superman’ Star Valerie Perrine Finally Finds Her Hero: "The Guy Should Be Sainted"