With at least 150 Afghan refugees moving to Savannah by February, one family tries to find a home

Please note that the names of the refugees have been changed to protect their identities as well as their families who remain in Afghanistan. The article has been updated to reflect updated numbers from Inspiritus.

It was around 2 a.m. on Aug. 15 when Mahdi heard his phone ring.

“Don’t go to work tomorrow," his brother warned him. "The Taliban have taken over the country.”

Mahdi nonetheless went to work the next day, creating Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations for the Afghanistan military.

Then, around 5 p.m., he heard gunfire.

The three-hour walk back to camp for Mahdi seemed different than usual. Normally, women and girls walked to and from school and work. This time, if there were any women to be seen, they sheathed their faces with burqas and chadarees. This time, there were men wielding guns and blocking main roads.

Mahdi’s brother had been right to warn him.

In late August 2021, as the United States withdrew its forces from Afghanistan, the U.S. military helped evacuate more than 125,000 Afghan citizens, many of whom had assisted the U.S. during the 20-year war that began shortly after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001. Among the evacuees: Mahdi, his cousin Shukria, and her two children. Missing were Mahdi's wife and four children, who still had not secured the requisite paperwork to apply for the necessary special immigrant visas (SIV).

Mahdi, Shukria and her children landed in Savannah last month, but getting from there to here required dangerous intersections, missed connections, endless red tape, and traveling from country-to-country and state-to-state until they could find stable housing.

Making their escape

Last August, when Mahdi, Shukria and her children arrived at the Kabul International Airport, the airport was jam-packed with tens of thousands of Afghan people trying to flee the country.

Mahdi said a U.S. advisor told them, “Stay at home, don’t go outdoors. Wait for my advice and I’ll give you the proper date and time, once things are settled, to head back out to the airport.” The advisor told them he would help them receive Humanitarian Parole, a temporary status that would provide them refugee benefits, so that they could leave the country in the next couple days.

Scared on the walk home, Shukria hid her personal documents under her headscarf. She worried that if the Taliban had captured her, they would assume she was trying to flee the country, and she, or, worse, she and her children would be murdered. Her husband had been murdered years earlier by the Taliban in a suicide-bombing.

Mahdi, Shukria and her children returned to their homes unscathed by 4 p.m. that same day. Three or four days later, after holing up in his house, Mahdi's visa arrived, but not the ones for his wife and children. They decided he should go, and he vowed to help move them to America when he made his way over. At least he would know his cousin Shukria, the only family he would have in a country he only saw in movies. Their advisor told them to go to the Kabul airport at 6 a.m. the next morning.

They arrived by 11 a.m. after navigating a city in the midst of falling to the Taliban. From morning through night, they stood and waited, starving and thirsty, and packed cheek-by-jowl with other Afghanistan people trying to flee. There weren’t enough planes to take everyone. Making it to the United States, at that point, seemed like a pipe dream.

The next day, Mahdi and Shukria and her children moved up in line, and had to jump into a large pool of water to get to the other side. Once they swam through the water, they were advised, the American military would help them board the plane.

At 2 p.m., they tried to get through the crowded gates of the airport. Eventually, they made it to the other side, where Mahdi overheard the news: 40 minutes after their arrival, members of the Taliban suicide-bombed the area they had just come through.

Shukria locked hands with her two daughters and shouldered her backpack. In the backpack, she carried identification documents, phones, and a flash drive with classified information gathered during her work helping Afghan women who served with the U.S. military to evacuate the country. After 20 minutes waiting in line, Shukria realized that, amidst the chaos, her backpack was empty. She made it on the plane amidst the chaos, but she and her two daughters had separated from Mahdi. She found two of Mahdi’s relatives on the plane, both women, and used one of their phones to contact Mahdi. After 24 hours, they were all reunited.

They boarded another plane from Qatar to Germany. After a more comfortable seven-hour flight, they stayed in Germany, at a military camp. Staying there for a couple of hours, they flew 14 hours from Germany to Washington D.C. From there, they were sent to Wisconsin.

When they landed in Wisconsin, American soldiers tried to welcome them — to no avail. The language barrier forced the American soldiers to make hand-motions. While they were trying to signal the Afghanistan refugees to perform basic tasks, like eat, sleep, and put on a jacket, Shukria, overcome, she said, by stress and PTSD, froze.

They remained at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin, for three months.

Refugee resettlement

After the International Organization for Migration (IOM) coordinated the family’s move from Wisconsin to Savannah, Inspiritus, formerly known as Lutheran Services of Georgia, an Atlanta-based resettlement agency that serves people displaced by domestic violence, natural disasters, and international conflicts throughout the Southeastern United States, is resettling the family.

Inspiritus has helped relocate individuals and families from countries such as Syria and Afghanistan to the United States since the 1980s. Since then, they would normally help relocate Afghan families to the United States if they had been receiving death threats from the Taliban. But when the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan in August, many Afghan people, especially those working with the Afghan government or U.S. military, needed to escape, which meant Inspiritus had to up-scale its operation from one employee in Savannah to seven.

“We're scrambling, and we've been scrambling a lot recently with this program,” said John Moeller, Inspiritus CEO.

In 2020, Inspiritus helped relocate five total refugees to Savannah. Since August, the organization has been in the process of relocating 150 Afghan refugees to Savannah. As of early December, 51 Afghan refugees resettled here.

Securing stable housing for the refugees, Moeller said, is the main difficulty.

Once Inspiritus picks up the Afghan refugees from the airport, they relocate them to a nearby church retreat center or hotel until the non-profit organization can secure housing for them, paying for their stay, usually for up to two weeks. Inspiritus tends to place the Afghan refugees in private apartment complexes rather than private properties mainly because private landlords “are not easy to work with,” said Moeller. Most private landlords tell Inspiritus case managers they don’t want to take the risk of housing refugees in their apartment complexes.

Options are inherently limited: Public housing is not an option. Refugees do not have the government-issued housing voucher necessary to obtain public housing in Savannah. Many of the Afghan refugees do not have a driver’s license, so Inspiritus can only help move the Afghan refugees into housing complexes near public transit.

And the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t made things easier: In-person, it was easier to convince property managers the Afghan refugees would be responsible tenants, but over-the-phone, it’s become more difficult, said Moeller. “We have encountered some housing discrimination."

Moeller provided an example: When an Inspiritus representative first called one property manager they were given a list of eligibility requirements. But when the property manager realized the applicant was an Afghan refugee, he asked for a credit check. The Inspiritus case manager responded that a credit check was not on the apartment complex’s list of eligibility requirements. Moeller met with the property manager and told them, “You’re throwing in extra things now.”

The property manager asked Moeller how they were going to pay their rent without a job. Moeller assured them the federal government “makes an investment” in their first month or two of relocating to the United States. Moeller added that, since Inspiritus started moving Afghan refugees to the United States in 2011, 100% of their Afghan refugees have secured employment and, within six months of their stay, are self-sufficient.

Settling into Savannah

At 9:30 p.m., on November 10, Mahdi, Shukria and her children landed at the Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport. By 11 p.m., a 40-year-old Savannah resident named Abbie Sprunger and an Inspiritus representative picked up the family.

Sprunger and her husband, the caretakers of the Wesley Gardens Retreat Center for the past six years, work with Inspiritus to host refugee families every year. In the past, they hosted a Sudanese family.

“Inspiritus had it all under control for years, then all this stuff hit the fan with Afghanistan,” said Sprunger. “So, I feel like part of my role in the coming months is to be building a bridge between the retreat center and Inspiritus.”

Since the abrupt pullout of Afghanistan, the Sprunger family has hosted in its six-bedrooms at the Wesley Gardens Retreat Center two other Afghan refugee families — one 12-year-old girl five weeks ago and a family of nine who, as of early December, were living there. The Sprunger family provided one bedroom for Mahdi, Shukria and her children for two weeks.

At first, when they met in the airport, the Afghan family seemed nervous, Sprunger remembers, but over the next two weeks, they slowly settled in. Together, the American and Afghan families enjoyed long cups of tea, cooked and ate large batches of Biryani, a Middle-Eastern mixed rice dish, and went on hour-long walks across the quaint Moon River, across from the retreat center’s 60 acres.

“We have just sort of seen an unraveling of their personhood coming out, more and more smiling and more and more laughing,” said Sprunger. “At first, we thought it was just a transitional commitment, but now it's very obvious that we'll be lifelong friends.”

To repay Sprunger’s kindness, Mahdi attends the same church, Christ Anglican Church, every Sunday.

On one Sunday in December, Mahdi, Shukria, her children, Sprunger, and other churchgoers — among them 14 other Afghan refugees who also used to live with the Sprunger family — stood at a front pew in Christ Anglican Church, listening to Lessons of Carols, which tells, in nine short Bible readings near Christmas, the story of the fall of humanity and the promise of the Messiah and the birth of Jesus.

One of the churchgoers, Josh Muehlendorf, met Mahdi, Shukria and the children at a church service a few weeks before. He’s known Sprunger and her husband for about a year through church, and heard they were helping an Afghan refugee family transition to Savannah one week before they arrived. Having served in an infantry unit in Afghanistan in the early-2000s, Muehlendorf felt compelled to help.

“Everyone comes back with some form of trauma,” Muehlendorf said. “And then to see what's happened recently in August, where it looks like it all failed, like it was all for naught, and knowing that the refugees were coming here and knowing that we might be able to help, it feels like we’re continuing the mission. Because we were over there to really help those people, and that failed. And now here's an opportunity to continue to help, so it's healing for us as well.”

The first way Muehlendorf helped the Afghan refugee family was simple: Take his dogs to the park at the Wesley Gardens Retreat Center. The children fell in love with the dogs in earnest, and, after a couple of dog-walks, Muehlendorf started driving the family wherever they needed to go around Savannah, from job interviews to grocery trips. Over time, Muehlendorf, Shukria and Mahdi bonded over working for the military alliance.

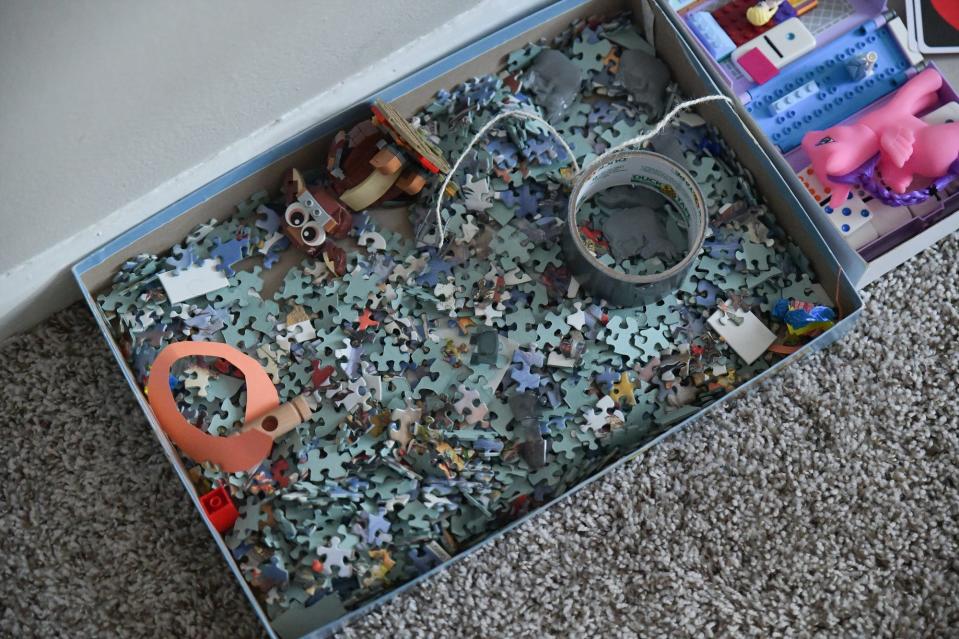

When he mentioned the family to his co-workers at Hunter Army Airfield, they too felt compelled to chip in. One of his co-workers started an Amazon Shopping wish-list and raised $3,000 through a GoFundMe campaign. With that money, they bought furniture, silverware and groceries, and helped move Mahdi, Shukria and her children into Muehlendorf’s garage, Inspiritus’ storage space, then, when it was ready, an apartment in Savannah.

'Call me, I'll try to see if I can help'

On a Saturday in early December, Mahdi walks into his place at his apartment, alongside Sprunger and her son, Eden, and notices a note of journal paper taped to the door, takes it down and reads it.

“Call me, I’ll try to see if I can help,” the note reads.

The neighbor must have noticed that her neighbor’s lights flickered off overnight. Either the property manager or the power company shut off the power; no one was sure. Sprunger tried to get the apartment to turn the electricity back on, but no workers were available throughout late Friday and the weekend. For the next two nights, Mahdi, Shukria and her children stayed at Hunter Army Airfield, as guests of Muehlendorf.

The fridge, filled with produce, leftover pasta and milk, leaves a lingering stale smell in the three-bedroom apartment. Mahdi lights a candle and places it on his living room table, pours a few cups of Sunny-D for his guests and sits down. The apartment is mostly empty, aside from a few plants, a Persian rug, and furniture. There are no signs, no mementos, no family portraits that these people had ever lived in Afghanistan.

As he ventures back outside, Mahdi, wearing a red flannel shirt, blue jeans, and a pair of D-Rose Adidas shoes, sits down on the apartment playground. A few minutes later, Muehlendorf arrives with Shukria, wearing a white burqa, and the children.

They sit cross-legged on the playground and start describing their story in Farsi, their native language, which is then translated to English over-the-phone by a Persian friend who lives in Skokie, Illinois, home to one of the largest Assyrian communities in the United States.

The family, meanwhile, is trying to integrate into Savannah. Mahdi, for his part, played soccer at the Jennifer Ross Soccer Complex with other refugees from the Middle East, on his first Sunday in Savannah. A few Saturdays later, he attended a barbecue hosted by members of the Hazara Community, a Persian-speaking ethnic group native to Afghanistan. Mahdi, like all other refugees Inspiritus helps move, has enrolled in a language class, a cultural orientation course and a money management course.

Shukria attends the same classes, in addition to Hope Academy English Club, an all- female refugee class every Friday. Shukria talks with her family via WhatsApp; they have told her that the Taliban is forcing the women and their daughters to stay home, barring them from enrolling in school or working. An Inspiritus job placement coach is helping Shukria apply for multiple jobs, including one at Chick-Fil-A.

“She's happy ... although it's very difficult starting from zero as she put it in a whole new country,” Shukria said through a translator. “She feels blessed to be starting over in a country where women and children have many, many rights that were stripped from them back home.”

Like Shukria, Mahdi applied for a job at Chick-Fil-A. In Savannah, he hopes to find an office job similar to the one he had with the Afghanistan military, but the language barrier has made that difficult. But, as of early December, Mahdi and Shukria, because they were waiting for their green cards to be processed, which typically takes three to four weeks, couldn't obtain full-time jobs yet.

Mahdi’s attention ebbs and flows. When he’s not telling his story, he’s keeping a close eye on his cousin’s daughters. They are everywhere: climbing the monkey bars, kicking a soccer ball with Eden, and tugging on their mom’s shirt.

Sometimes, Mahdi can’t help but look off into the distance, past the Spanish moss hanging from the trees. He still has flashbacks. Of a war lost, a home left behind. Not a night has gone by in the United States where Mahdi hasn’t had a nightmare. He thinks about his wife and children, who remain in Afghanistan. He talks to them every day over video call and texts or via WhatsApp. He sends whatever little money he earns, while trying to get their papers together and asking Inspiritus to help them move to America, and ultimately, Savannah.

“Daddy, when are you going to come back home?” his son often asks his dad in those video calls. A question his dad can't answer just yet.

War, famine, persecution, economic and political instability — for these reasons and more, an individual makes the heartbreaking decision to uproot from all that he or she knows to seek a better and safer life in another land. Yet, within the international community, all immigrants are not categorized the same. Like those old logic statements on standardized tests, all refugees are migrants, but not all migrants are refugees. Knowing the difference among these categories can help dampen the fiery political language surrounding the topic of immigration and lead to healthy, respectful dialogue that honors each person’s humanity.

Migrant: An umbrella word that captures any person who chooses to move from his or her homeland for any reason, but not necessarily because of a direct threat of persecution or death.

Asylum seeker: A person who has fled persecution in his or her homeland and seeks safe-haven in another country, but who has not received any legal recognition or status. Asylum seekers may be detained while waiting for their cases to be heard, as is the requirement in the U.S. The many migrant Honduran women and children in the caravan now in southern Mexico plan to request asylum in either Mexico, Canada or the U.S.

Refugee: A person who has been forced to flee his or her homeland due to persecution, such as harassment, threats of death, abduction or torture, based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, sexual identity, or membership in a particular social group. A refugee is afforded legal protection by either the host country and/or the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The U.S. has limited the number of refugees it will accept annually and all refugees are screened in advance before being allowed to resettle in the U.S. The screening process can run from two to as many as 10 years or more, and includes background and security checks by multiple U.S. agencies. Al Khazraji and his family are refugees.

Internationally displaced person: A person who has fled his or her home community but has not crossed an international border to find safe haven. IDPs legally remain under the protection of their own governments, even if that government is the cause of their flight, such as the situation in Syria, where citizens have fled cities to find safety in another part of the country where the ongoing civil war has not reached. Once they cross an international border and seek UN protection, they may assume the legal protection of refugees.

Immigrant: In the U.S., a person born in another country who has lawfully migrated to the U.S. is technically a “legal permanent resident” and holds a green card (permanent resident card).

Undocumented or unauthorized immigrant: A person who leaves his or her home country and enters the U.S. outside of standard legal application and approval processes, and who does not have a current visa or green card authorizing him or her to remain in the U.S.

Sources: UNHCR, unrefugees.org; HIAS, hias.org; usa.gov

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: With American withdrawal, some Afghan refugees seek a home in Savannah