What I learned from my first total solar eclipse

I’ve always thought eclipse chasers—these people who spend thousands of dollars flying around the world to spend two minutes looking at a solar eclipse—were a little nutty. I mean, that’s a little extreme, right? If you want to see what a solar eclipse looks like, type solar eclipse into Google, right?

Of course, I get that an eclipse is supposed to be better experienced live, in the same way that seeing a band perform live is more exciting than listening to a recording. But the way these people talk? “Life-changing?” “Addicting?” “Spiritual?” That, I’ve always thought, was a little much.

A total eclipse of the sun is when the earth, moon, and sun are all lined up perfectly, so that the moon precisely blocks the sun for couple of minutes. (How come its silhouette is exactly the right size to block the more distant sun? Pure coincidence.)

That’s the moment of totality—where the moon is positioned fully between you and the sun, so that all you see of the sun is a ring of fire around a jet-black circle. It supposedly looks like this:

Getting to see a total eclipse is relatively hard. There were just 62 total eclipses during the 20th century. Even then, the moon’s shadow carves out a narrow path, only 70 miles wide, where you can experience totality. (Outside that band, you see a partial eclipse, where you see the sun with a rounded bite taken out of it—kind of like the Apple logo.)

So to experience totality, you have to be in the right place in the right time—and have the right weather.

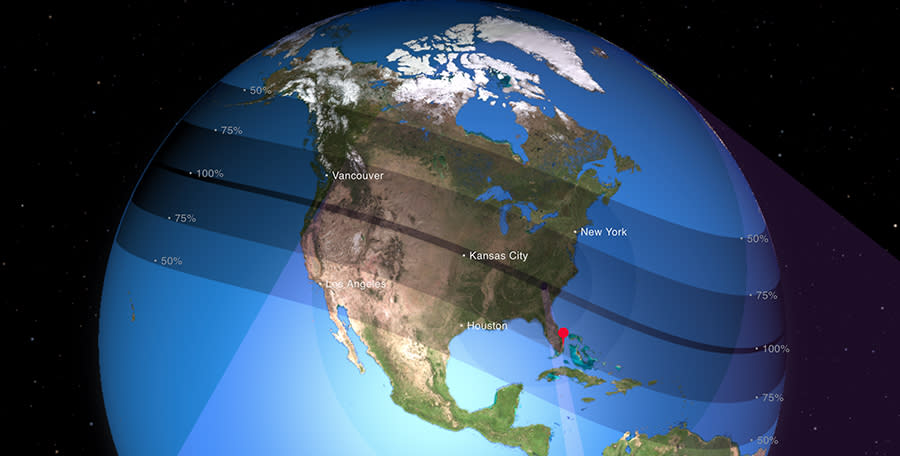

Experts were raving about how rare and special this week’s eclipse would be. They called it the “Great American Eclipse,” because (a) its path would cross the entire continental USA, for the first time in 99 years, and (b) the total eclipse would be visible only from this country. Totality would pass through 14 states, passing over the homes of 12.2 million Americans.

It would also fall during the final days of school summer vacation. In other words, all the planets were aligned for me to make my own first trip to see a total solar eclipse.

Not for my benefit. For my kids. Obviously.

Where to go

NASA’s websites featured some great tools for planning a visit. Almost every state in the U.S. would be able to see some of the eclipse. But we wanted to experience totality if we could.

NASA’s interactive map made it clear that, for us, the closest spot would be South Carolina. So I booked a plane, a car, and a cheap hotel, and started getting my kids excited.

Three days before the eclipse, though, it became clear that South Carolina was not the place to be this time; almost the entire state would be covered by clouds on the big day!

Of course, a total solar eclipse is very cool even if it’s cloudy. You still feel a crazy rapid temperature drop, see the day rapidly turning into temporary night, and hear animals and bugs going crazy. But you miss the grand prize: Looking into the sky and seeing the eclipse itself.

Well, dangit. Now what?

Well, I’d come this far. I bit the bullet and canceled our reservations.

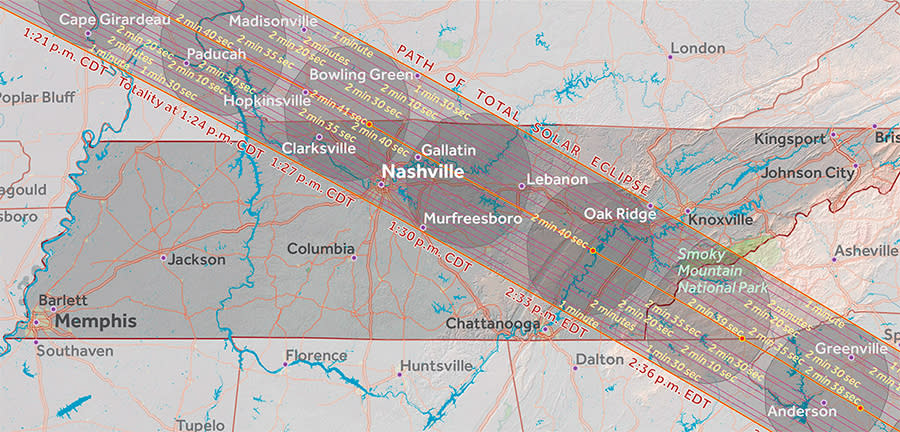

The next closest spot on the eclipse’s path of totality seemed to be Nashville, Tennessee—a great place for a family trip even without an eclipse. Better yet, the weather was supposed to be clear! Nashville was hosting all kinds of special events. At their science museum, for example, there would be talks and booths and exhibits. At the baseball stadium, the mayor was hosting a massive viewing party.

All the flights to Nashville were sold out. So we flew to Memphis instead, and drove the 3.5 hours to Nashville.

The night before, in our hotel room, my sons (ages 20 and 12) and I planned our strategy. Nashville would experience 1 minute, 55 seconds of totality; but smaller towns 30 miles away were closer to the eclipse’s center line. Gallatin, Tennessee, for example, would have 2 minutes, 40 seconds of totality. Jeffrey, my seventh grader, insisted that we skip the festivities of Nashville and go for the longer eclipse experience.

“You realize that, with all the traffic, we’ll have to sit in the car for two extra hours to get to Gallatin—for 45 seconds more eclipse?” said Kell, his older brother. But Jeffrey was adamant.

The big morning

We arrived at Triple Creek Park in Gallatin two hours before the start of the eclipse. This is a vast public park—acres and acres of soccer fields, baseball fields, field fields. There were lots of people there for the eclipse, but the park wasn’t what you’d call crowded in any sense; finding places to park our car and ourselves was easy.

Here and there, we saw people with telescopes or huge telephoto camera lenses. Everyone was incredibly friendly; there was a sense of shared excitement. The day was blistering hot, so most people found shady trees for waiting.

The eclipse began at 11:28 a.m. For an hour, it was OK. You could wear your cardboard eclipse glasses, look up at the sun, and see the growing rounded bite taken out of its side. “It’s a Pac-Man,” said almost everyone. Interesting, but slow.

But then, as 12:29 p.m. approached, things began to get wild. We could feel the heat ease off fast, as more and more of the sun got blocked. The cicadas that had produced a loud, steady background rattle all morning suddenly went quiet.

And then, with a minute to go, the magic began. The whole world began to dim. But here’s the thing—it wasn’t dark like nightfall. This darkness had a silvery-grey tint to it. It was as though someone had put a giant Instagram dimming filter on everything you could see. Completely otherworldly and strange and beautiful.

And then, suddenly, the eclipse hit totality: The sun was completely blocked by the moon. All around us, we could hear people crying out. These weren’t crowd noises like you’d hear at a circus, baseball game, or theater—it was gasps of awe and emotion, a collective sound I’d never heard from a crowd before.

My eclipse app’s guide voice announced that it was now safe to remove our glasses and look directly up at the sun.

Oh, my, god.

While we’d had the glasses on, all we could see was the bright yellow crescent of the sun—and around it, blankness. No color, no detail.

But with the glasses off…!!

Where there should have been the sun, there was a jet-black perfect circle, sharp and laser-cut. Around it was the corona—a blazing intense spill of the sun’s atmosphere. All of it was suspended against a deep blue sky. That’s what I remember: Intense black circle, intense ring of white, intense glowing blue.

Yes, there is color in an eclipse—vivid, iridescent, alien. Almost every solar-eclipse photo lies. All of those Google image searches? They’re baloney. They show a black ball against a black sky, and that is not what it looks like.

I’ve tried to Photoshop the right color scheme into this photo:

We could see some stars—against blue, not black.

Here’s another reason why no photo can ever represent a total eclipse: Because a photo can show the corona only as bright as your screen (or piece of paper)! You don’t get any sense of how stunningly bright and pure and intense that fire is. It’s hundreds of times brighter than your screen.

Our eyes can detect a much greater dynamic range (the scale of brights and darks) than any camera can. What I learned that day is that a total solar eclipse is almost alone among the things we experience, in that you can’t photograph it. To see what it looks like, you have to be there.

When I looked around us, I saw a strange, gorgeous fake twilight. There was what looked like a 360-degrees “sunrise” around the entire horizon, and the sky ranged from dusky blue to deep violet.

When I looked up, though, my heart raced. The intensity, the dazzling colors, the freakishness of that sight—a jet-black hole where the sun should be! I’m not a touchy-feely person by any stretch, but this was a spiritual experience; I was so moved, and I could tell that my sons were, too. I could easily see why ancient civilizations assumed that some god or mystic force was responsible for total eclipses.

(I love this description by retired NASA astrophysicist Fred Espenak, who’s witnessed 27 solar eclipses: “You feel something in the pit of your stomach like something is wrong in the day, something is not right,” he told Time. “As totality begins, and the shadow sweeps over you, the hairs on the back of your neck and arms stand up.”)

I’d been warned not to try to take pictures of my first eclipse; the last thing you want is to miss the magic while you’re futzing with your gear. So during the 160 seconds of totality, I allowed myself about 10 seconds to snap pictures (Sony a6000 SLR, solar filter, 210mm lens). They’re not great pictures—you really need much more zoom—but here’s the idea:

As the moon began to edge out of the sun’s way, we were treated to a moment of the “diamond ring” effect as the sun breaks past the right edge of the moon:

And then, as quickly as it had begun, the process reversed itself. Daylight returned, and the world’s colors faded back in. The temperature shot back up. The crowd cheered. People ran to check their cameras, or babble with their families, or wipe tears from their eyes.

The first-timers, in particular, had been somehow changed. We’d all seen something freakish, rare, beautiful, shocking, historic—and much, much bigger than ourselves.

I had set up a GoPro on a tripod to film the whole scene, hoping to capture the fading light and the sounds of the event. Unfortunately, I was too wrapped up in the event to notice that another guy set up his camera and tripod right in front of mine, partially blocking the shot. Sorry about that, but you still get the idea—you can see the light fall, and hear the crowds and the confused cicadas—in this time-lapse video:

The modern-age eclipse

Actually, this wasn’t my first solar eclipse. I can still remember my parents showing me one in the backyard in Cleveland when I was 7 years old—and using a stack of color film negatives to protect my eyes! (A little research reveals that, first of all, that’s not a safe way to view an eclipse—and second, we weren’t in the path of totality. But I remember everybody being pretty excited anyway.)

What’s different, of course, is time and technology. The internet made planning our eclipse trip a snap—we could see the path of totality and observe the weather. Phone apps guided us through the experience. Those cheap cardboard eclipse glasses made it safe to look up with confidence. Social media made it possible to share the experience around the world in real time—both the exhilaration of seeing the eclipse, and, for some, the heartbreak of being thwarted by unexpected clouds (as Nashville viewers ultimately were).

The next total eclipse will come to the Earth in July 2019, but most of it will be wasted on empty ocean. (You’ll be able to see it in Chile and Argentina, but it’ll be winter time, and therefore possibly cloudy.)

The next one to come to the U.S. will occur in April, 2024—seven years from now. It’ll fly up from Texas to Maine, like this:

Take it from a guy with a changed attitude: You should try to be there.

I’ll be joining you.

More from David Pogue:

Samsung’s Bixby voice assistant is ambitious, powerful, and half-baked

Is through-the-air charging a hoax?

Electrify your existing bike in 2 minutes with these ingenious wheels

Marty Cooper, inventor of the cellphone: The next step is implantables

The David Pogue Review: Windows 10 Creators Update

David Pogue’s search for the world’s best air-travel app

The little-known iPhone feature that lets blind people see with their fingers

David Pogue, tech columnist for Yahoo Finance, welcomes nontoxic comments in the comments section below. On the web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. You can read all his articles here, or you can sign up to get his columns by email.