The Last Time Actors and Writers Both Went on Strike: How Hollywood Ended the 1960 Crisis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1960, the crumbling infrastructure of the Hollywood studio system was shaken by a one-two strike launched by two essential branches of its workforce — the writers and the actors. Since neither job was yet considered on the cusp of obsolescence, management was forced to negotiate with labor and reach an accommodation. Both sides had incentives to make a deal that shared the wealth and kept the shop floor running. In the end — and this might be the sad difference between 1960 and 2023 — they saw each other as collaborators rather than mortal enemies.

The reason for the “double strike” by the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild was, of course, television, the technological menace that had transformed the business but not the fine print in the employment contracts. Both sets of artists wanted a bigger cut of the post-1948 feature films that had been sold to TV and a solid deal for profit sharing in the future. Health benefits and working conditions were also on the table.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

The key issue for both guilds was residuals — that is, payment fees for work done and recycled on film and over the airwaves. The root word implies “left over,” but by 1960, residuals were looking like the main course. Even more than the libraries of feature films on the auction block, the syndication of filmed sitcoms like I Love Lucy, The Danny Thomas Show and Father Knows Best was already generating millions of dollars in revenue for the producer-owners; the creators and performers wanted a fair share of the windfall.

(Since you ask: The history of residuals in the entertainment industry dates to the beginning of the age of mechanical reproduction, with the introduction of the phonograph being an inflection point. From about 1910 onward, singers received royalties based on record sales. Radio and jukeboxes complicated the rewards structure, but the American Federation of Musicians — probably the most feared of all performer unions, known for its hardball tactics — was ready to do battle with what it called “the mechanical monsters.” As early as 1932, it had obtained residual deals for the recorded work of singers and musicians broadcast over the airwaves. With the onset of television, an eventuality not foreseen in the original contracts of the artists who created and appeared in the feature films, serials and shorts that made up so much of the content of the medium in the late 1940s and ’50s, calculating payments got even more complex. Unless artists had been smart enough to negotiate a profit-sharing arrangement back in the day, they were usually shut out from additional revenue down the line. No fools, Abbott and Costello had secured a share of profits for the theatrical reissues and TV rights of their Universal films and cleaned up. By contrast, the Three Stooges got not a dime from their Columbia shorts, made in the 1930s, which were broadcast in saturation rotation in virtually every TV market in America.)

WGA and SAG sought a residual formula that would give standardization and certainty to creators and performers. The talent, a spokesman for the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists said in 1960, is “entitled to get a portion of all this money that is floating around. It is as simple as that. Where would everybody be without talent?“

The WGA threw down the gauntlet first. On Jan. 16, 1960, citing “a consistently uncompromising attitude on the part of producers,” WGA president Curtis Kenyon, a former screenwriter now toiling in television, called a “two-pronged” strike against both film and television production. Among the demands: residuals “in perpetuity” and not merely for six reruns; a cut of the profit stream from foreign distribution; and more equitable working practices, particularly concerning speculative, or “spec,” writing.

Having stashed away a backlog of scripts, the producers figured they could bide time and wait out the writers. For instance, 39 scripts for The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis were already locked, and the show remained in production.

Actors were a more visible and valuable commodity. “The walkout of the Writers Guild over the weekend does not worry the producers, but a strike of the actors because of the refusal of the studios to meet their demands would be a death blow to the business,” noted Billy Wilkerson, then–editor-publisher of The Hollywood Reporter, usually no friend of labor.

The actors had a formidable fighter in their corner in the person of SAG president Ronald Reagan, the former Warner Bros. star who had downsized into television and, since 1953, had served as host of CBS anthology series General Electric Theater. As SAG’s leader from 1947 to 1952, when Hollywood found itself in the crosshairs of the postwar anticommunist crusade, Reagan had successfully steered the guild through its most treacherous period. In 1947, he had eloquently defended the patriotism of the motion picture industry before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, receiving some of the best reviews of his career. Today, Reagan’s actions during the blacklist era have become more controversial (heck, everything about the era is), especially his role as an off-the-books FBI informant and his participation in “clearance” procedures, whereby actors accused of ideological malfeasance would have to explain or recant before a star chamber of industry apparatchiks. Yet his peers thought enough of Reagan to draft him in 1959 for an unprecedented sixth term as SAG president. Anticipating the upcoming battle with the studios, they wanted a trusted and experienced player on the field to represent their interests. “Ronald Reagan is playing his greatest part to the least applause,” was the line going around town.

SAG proceeded carefully. On the night of Feb. 17, 1960, at the home of Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, 100 members met to authorize a strike, figuring that a threatened work stoppage would put them in a better bargaining position.

Yet the Association of Motion Picture Producers, represented by executive vice president Charles Boren, refused to budge on the actors’ demands. “No payment twice for the same job,” as Variety’s Bob Chandler characterized their position. “Nothing at all, they said, and we won’t discuss it.”

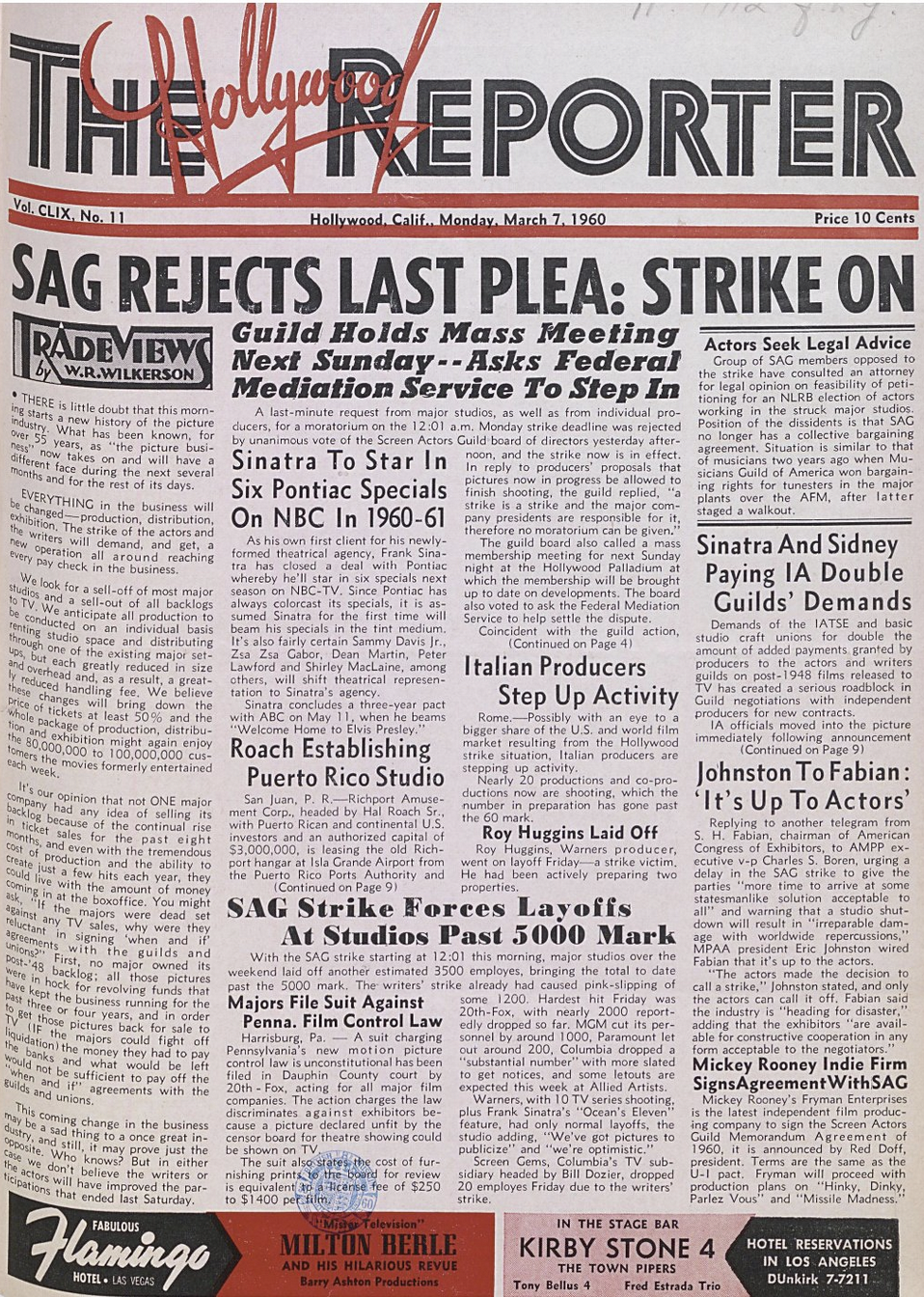

On March 7, SAG called the strike, and tense series of contract negotiations ensued immediately. At Reagan’s side, doing the heavy lifting, was John L. Dales, the savvy counsel and executive secretary for SAG. Dales was the hands-on detail man who checked the contract language line by line. Unlike the strike by the WGA, which targeted both film and television production, the SAG strike was aimed at film production alone. Work on eight features — including The Wackiest Ship in the Army and Butterfield 8 — screeched to a halt.

The decision to strike was not universally popular with the SAG rank and file. “Actors are not morally justified in striking and causing backlot workers to be laid off,” said actor Glenn Ford, speaking for a group of 40 dissidents. “If it weren’t for the guys in the crews, we wouldn’t be actors.” Tony Curtis, getting in touch with his Bronx roots, shot back: “If Glenn Ford feels our union didn’t do a good job, let him join the butchers’ union.”

Leave it to gossip columnist and SAG member Hedda Hopper (who made frequent cameo appearances in film and TV as herself) to resurrect the specter of Hollywood past. “Isn’t it coincidental that at a time when some of the more liberal producers are hiring Communist writers that this strike came up?” she said. Hopper was referring to the recent announcements by producer-director Otto Preminger and producer-star Kirk Douglas that screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, the most notorious member of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten, was to be hired under his own name for Exodus (1961) and Spartacus (1960), respectively. In terms of reading the room, she could not have been more wrong. The writers and actors had no thought of smashing the capitalist machine; they just wanted a bigger slice of the pie.

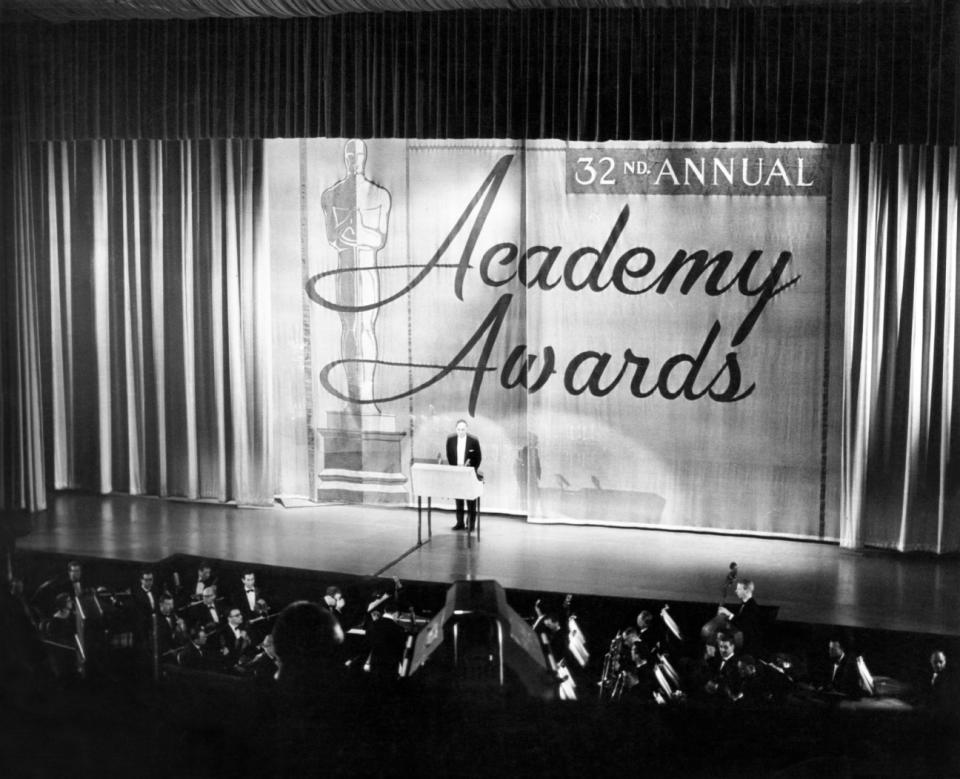

On the night of April 4, in the middle of the strike negotiations, both sides paused to attend the 32nd Academy Awards at the Pantages Theatre. Reagan had hoped to surprise the audience with an announcement that the strike had been settled, but negotiations remained at an impasse. The emcee for the evening, of course, was Bob Hope, hosting the Oscars for the ninth time. “Welcome to Hollywood’s most glamorous strike meeting,” he said. “I never thought I’d live to see the day when Ronald Reagan was the only actor working.”

Hope received a huge ovation when, to his surprise, he was presented with the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. “I don’t know what to say,” he said, genuinely moved. Then he delivered a line that must have pleased the WGA: “I haven’t writers for this kind of work.” (Indulge me with one more Hope wisecrack, a line that may now seem prophetic. Introducing the five nominated songs, he said, “We wish to announce we pay for all the sheet music, buy all our own records, and none of the young ladies has been technically augmented.”)

On April 8, SAG and the Association of Motion Picture Producers came to terms. The guild dropped the demands for residuals on 1948-60 films and accepted instead a huge payment to the SAG pension fund. For films made after 1960, however, actors would receive a percentage of receipts, minus deductions for distribution expenses. Producer contributions to the guild’s health and welfare funds were also increased. Reagan, even then tax-averse, pointed out that the pension payments, unlike residuals, were tax free, whereas residuals were taxable as gross income.

Asked how he felt at the end of negotiations, Reagan said, “Very happy.” Boren of the AMPP agreed. “Very happy indeed.” (There’s a coda here: In 1981, in one of the defining acts of his presidency, Reagan fired more than 11,000 air traffic controllers who were striking in defiance of a court order. He reminded Americans that he was a union man who had led the Screen Actors Guild out on strike — a legal strike.)

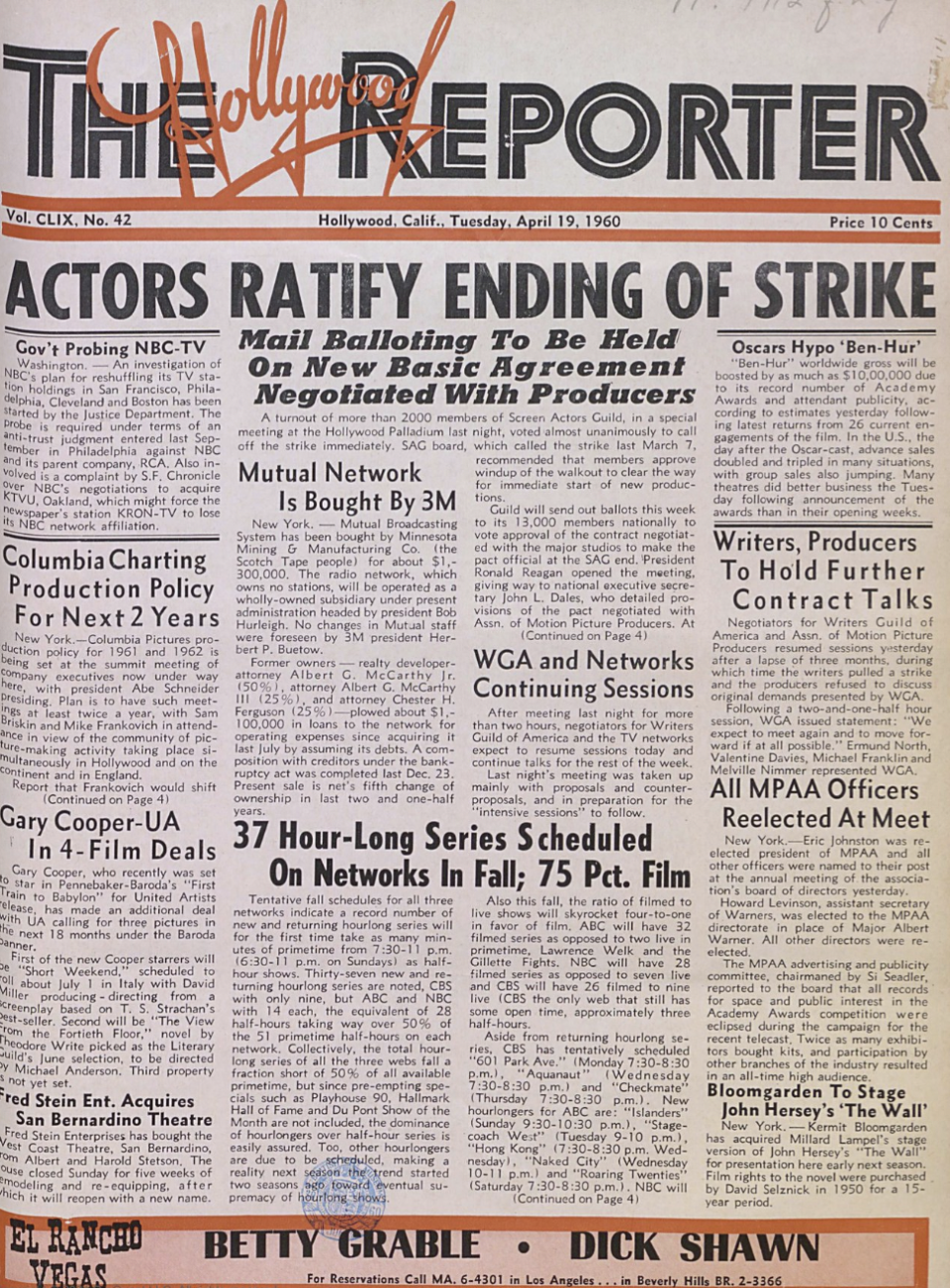

On April 18, 1960, at a mass meeting at the Hollywood Palladium, more than 2,000 members voted overwhelmingly to affirm the deal. One of the few voices raised in opposition came from Hopper, still red-baiting and shilling for the producers. She was hissed down by the crowd.

SAG and the producers then issued a kiss-and-make-up joint statement: The agreement “is fair and equitable and will lead to stable labor-management relations in the industry.” Before the ink was dry, producer Jerry Wald had resumed production on Let’s Make Love.

With the actors back at work, the writers had less leverage. “You actors are now running the business,” admitted a depressed screenwriter to a SAG colleague. WGA leaders figured the best strategy was to use the SAG settlement as a model. Unlike SAG, however, expert negotiators were not at the table for the writers and the talks stalled. Consensus opinion in the trade press asserted that WGA was “being injured by the worst public relations program in the history of management disputes, and that amateur negotiators, no matter how hard they work, are lambs among wolves at the negotiating table.”

Not until WGA sent in its own wolf, Evelyn Burkey, executive secretary of its East Coast branch, did the writers close the deal — first with the Alliance of Television Film Producers and the Association of Motion Picture Producers (June 19) and then with the three major networks (June 25).

The WGA agreement set forth a formula for residuals tied to worldwide grosses: In addition to the original paycheck, 40 percent of same would be spread over five domestic reruns with 4 percent of the absolute gross paid out in perpetuity. Both sides agreed that the negotiation “marks a milestone in the history of labor-management relationships,” assuring “the perpetuation of our industry” and “increased revenues” for all concerned. Once all the smoke had cleared, THR columnist Mike Connolly expressed the prevailing sentiment around town. “Thank God it’s over,” he said. “Let’s go to work.”

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Meet the World Builders: Hollywood's Top Physical Production Executives of 2023

Men in Blazers, Hollywood’s Favorite Soccer Podcast, Aims for a Global Empire