Last Stand in Coal Country

It’s a week before Christmas and the sons and daughters of Alabama miners are playing musical chairs in an old school at Tannehill Ironworks State Park, 30 miles south of Birmingham. A mom presses play, and the music starts. It’s Stevie Wonder.

Someday at Christmas we’ll see a land

With no hungry children, no empty hand

One happy morning people will share

Our world where people care

More from Rolling Stone

Guns, Grift, and Gore: The Life and Times of an Arms-Dealing Hustler

Report: Kanye's Anti-Semitic Rhetoric Led to Assaults, Vandalism

Did This Miami Woman Get Rich Selling Real Estate -- Or Scamming Covid Loans?

The music stops and a boy shoulders a girl out of the way. A grown-up scolds him.

“Play nice, Santa is watching.”

The room is filled with Lego sets, Barbies, and bicycles with training wheels. The kids are allowed to pick out one toy after the game ends. They circle the gifts with saucer-size eyes. Suddenly, they squeal. Santa is here to read “The Night Before Christmas.” They settle at his feet in front of a wood-burning stove.

It’s a Hallmark scene if you don’t look too closely. All the toys have been donated by the United Mine Workers of America. The kids’ parents are union miners. They say they work six or seven days a week, 14 hours a day deep under the earth at the Brookwood Mine, one of the largest in Alabama.

Well, they used to work there. On April 1, 2021, 900 miners went on strike. Nearly two years later, some have crossed over, but 650 still walk the picket line. Their demands seem unremarkable, even in an America where workers scratch and scrape to get a fair deal. Back in 2016, the miners took an average wage cut of $6, from $28 an hour to $22, when Walter Energy, the mine’s longtime owner, went bust and was bought by Warrior Met Coal. Soon the company was flush, paying out millions in dividends and exec bonuses. In 2021, it was time for a new contract. The Brookwood miners just wanted their six bucks back.

Instead, Warrior Met offered $1.50 an hour in raises over five years. So the miners went on strike, just like many of their fathers and grandfathers had done before. But this time was different: Warrior Met Coal has shown zero interest in negotiating. The Brookwood strike turns two years old next month and is now the longest strike in Alabama history. The company claims to have made eight proposals over the past two years, but the miners say that’s a lie. (Warrior Met had no comment about any of the miners’ allegations.)

“They change one line and say it’s a new proposal,” claims Larry Spencer, UMWA’s District 20 vice president and a union negotiator. “But nothing actually ever changes.”

Spencer is responsible for the union here, and the 65-year-old ex-miner looks weary as he sips a cup of coffee. He stands in a hallway between the room of innocence where the kids believe Santa is real and the talk going on in the dining room. There, the grown-ups trade stories about odd jobs they’ve taken, and car repairs postponed. They glare at the ground when someone mentions a former union brother who has crossed the picket line and gone back to work.

The party and toy giveaway ends at one that afternoon, but around 1:30 a car with a Confederate front license plate screeches up to the school. A man bounces up the stairs and finds toys for his kids. He is impatient and short-tempered, blaming his wife for getting the time wrong. He spots Spencer and starts jabbing a finger at him.

“I know you’re not going to tell me the truth,” says the miner, “but I’m going to ask you a question anyway.”

Spencer is a big man with kind eyes, but he has his limits. He overturned a table of the Democratic Socialists of America in 2021 when the group set up a stand at a strike rally without his permission. He exhales and offers something between a grimace and a smile.

“I don’t know if calling me a liar is a good way to start, but what’s on your mind?”

The man sputters a bit.

“You know what’s going on.” He trails off and hesitates, seemingly reluctant to voice his next thought. “They have no interest in settling. They just are going to wait and wait. They want to kill the union.”

He pauses and looks Spencer in the eye.

“Well, what do you think of that?”

Spencer stares back.

“I think you might be right.”

The man is momentarily flummoxed.

“Well, at least you told me the truth.”

He heads toward his car, a little less malice in his step. He then turns back to Spencer.

“Merry Christmas.”

THERE’S NEVER BEEN a worse time to be a miner, and that’s saying something. As of 2021, fewer than 40,000 miners remain in the country, down from 91,000 in 2011. One explanation is America’s awakening to the environmental implications of coal, but the true answer is more capitalistic than climate: Coal is now more expensive than natural gas produced from fracking, another environmentally dubious source of energy.

That doesn’t change the fact that working at a place like the Brookwood Mine is dangerous business. Every shift, you take a long ride down an elevator toward the center of the Earth, where you are met by darkness and a wall of noise. A lot of prospective workers don’t make it past that point. They see the chaos and claustrophobia and say hell no. They ride right back up, earning the nickname “yo-yos.”

Those who keep going have another hour ride in a rickety rail car to their mine work. That could be four miles away. Your life is constantly in danger. Don’t believe it? Just stop at West Brookwood Church. Out front, there’s a plaque and 13 pine trees planted for the 13 Brookwood miners killed in a 2001 cave-in.

The miners say the company expects an 80-hour work week — hiring more workers would mean the company would have to pay out more benefits. In the winter, even the day-shift workers arrive in darkness, spend the day in darkness, and leave in darkness. But that is the least of your concerns. Work-life balance is a phrase said in a foreign language. You won’t really know your kids as you miss every ballgame, every doctor’s appointment, and every field trip in service of King Coal.

Miners, though, get something in return. In exchange for owning you, the mine offers a good wage, and with all the mandated overtime you can earn around $95,000 a year. There is a gold-plated insurance plan to help you cope with the inevitable respiratory illnesses and joint destruction that comes with a career in mining. The United Mine Workers of America looks after you and makes sure you get what you deserve.

Warrior Met seems to be doing its best to detonate this uneasy compromise. In 2011, Walter Energy, Brookwood’s previous owner, bought Western Coal, a Canadian coal conglomerate, for $3.3 billion. This was a disastrous overextension for the company.

Warrior Met kept saying, ‘Work with us. Work with us, and if you do, we’ll take care of you,’ ” says a longtime Brookwood miner. “This ain’t my definition of taking care of us.

By 2015, Walter’s CEO, Walter Scheller III, received $6.3 million in total compensation, but he wasn’t able to prevent Walter Energy from filing for bankruptcy that year. Walter Energy’s debt was bought by a group of hedge funds, including Apollo Global Management, a firm known for wringing out profit from distressed companies with little concern for their employees. The deal was that they would pay off the company’s debt in exchange for acquiring Brookwood and another, smaller mine. The investors had one nonnegotiable demand before they would close the deal: The miners’ contract had to be thrown out. A bankruptcy judge agreed.

Walter Energy was reborn as Warrior Met. The new company, not exactly casting a wide net looking for a new CEO, landed on a familiar face. The new boss was the old boss: Walter Scheller. He wasn’t the only Walter exec to make the transition.

The miners say the new/old company informed them that their jobs would go away unless they took a 20 percent pay cut and that they’d lost a mountain of other benefits: Double time for Sunday and time and a half for Saturday were eliminated, they say. Miner insurance had been so good it got you moved to the front of the line at the doctor’s office. The miners say that ended as walk-in, walk-out health care was replaced with an 80-20 plan where families could be responsible for up to $7,000 for hospital stays.

Meanwhile, Warrior Met was paying out huge bonuses to Scheller and dividends to its shareholders. Sen. Bernie Sanders was so outraged he held Senate hearings on the strike in 2021.

“I invited Mr. Scheller, the CEO of Warrior Met, to testify at this hearing,” said Sanders. “I wanted to ask him how, over the last five years, Warrior Met could afford to provide $1.5 billion in stock buybacks and dividends to its wealthy shareholders and huge bonuses to its executives but cannot afford to treat his workers with dignity and respect.”

Scheller didn’t show up.

It didn’t stop there. The UMWA claims they also conceded 25 percent of their positions and that Warrior Met turned those slots over to contract workers with no loyalty to their union co-workers. The miners describe a new policy stating that if you were late or absent more than three times in a year and didn’t give 24 hours’ notice, you would be fired. It sent a chill through the miners and their families as most emergencies don’t announce themselves with a 24-hour notice. This has left people making hard choices. In 2020, Haeden Wright, the head of the UMWA auxiliary who organized the Christmas party, thought she was having a miscarriage, but she decided not to call her husband, Braxton, at the mine and pull him from work, lest he be given a strike. She drove herself to the hospital.

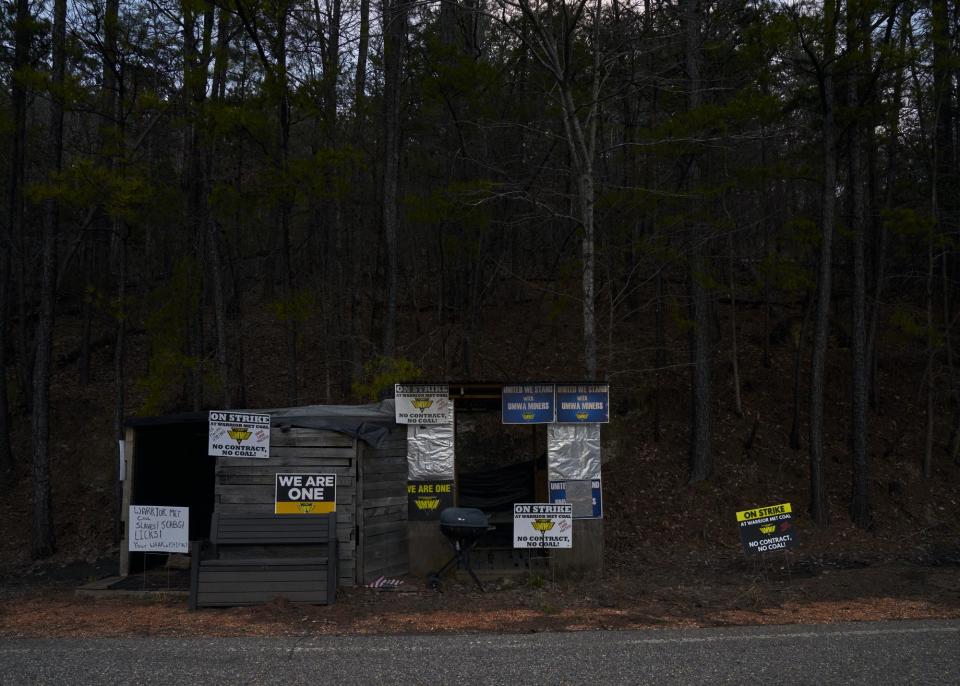

Meanwhile, Warrior Met began enforcing chickenshit policies to let the miners know who was boss. According to the miners, the company proclaimed that if you were not standing within a taped-off square for a pre-shift safety brief, you would be written up and face dismissal. “They just wanted to show us they had all the power,” a miner tells me on a picket line across from the mine. “It would be pouring rain and they wouldn’t let you stand 10 feet away under cover so you didn’t get soaked.” The miner spits. “That shit had nothing to do with safety.”

THE BROOKWOOD STRIKE raged hot at first. Sen. Sanders came down to offer his support, and Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine threw a benefit concert. Striking miners flew to New York City and protested outside of the Wall Street offices of Black Rock, Warrior Met’s largest shareholder at the time, urging them to put pressure on Warrior Met to settle the strike. Eventually, Black Rock conceded and issued a statement urging Warrior Met to bargain in good faith. It was a big moment for the union. Warrior Met just ignored them.

Nearly two years in, most of America seems to have forgotten about the miners’ strike. There’s been much more attention paid over the past two years to unionizing efforts at an Amazon warehouse 25 miles up the road in Bessemer. But mention the plight of miners and some liberals get nervous. They mumble something about the climate and look away. The reality is that the Brookwood Mine doesn’t produce thermal coal, a.k.a. dirty coal, but a metallurgical version that is considerably less toxic than thermal coal and essential in the manufacturing of steel. But that doesn’t seem to matter.

This pisses off Haeden Wright.

“You either support workers or you don’t,” she says. “We supported Starbucks and Amazon. If you’re for workers, you have to support all the workers.”

“TRUST” AND “SAFETY” are sacred words for miners. It is why they prefer working with regular partners, fellow travelers who can convey a saving action with a nod or tilt of their arm. Generations of miners relied on each other and trained one another up. Dedrick “Mudd” Gardner, a miner with 15 years of experience, gave me an example. “There used to be a time when a new miner would start and someone would say, ‘OK, that’s my work son. Stick the boy with me until he learns the ropes, until he is safe.’ You work in a mine, you need trust.”

Warrior Met ended that. Crews that had been working together for years were broken up and dispersed — all, the miners claim, to make them weaker. Warrior Met then began holding job fairs out of state in places like West Virginia and Kentucky, despite Alabamians being desperate for the well-paying gigs that mine work provided. The new hires clashed with the old guard, leading to tensions, according to multiple miners.

“They were trying to crush our culture,” says Gardner, a miner with more than 15 years of experience. “It was pretty clear.”

I’m talking with Gardner down in his basement bar, nicknamed the Mudd Palace by his fellow miners. He blasts smooth jazz from the speakers and pours me a vodka on the rocks. A few minutes later, we are joined by Marcus George, his best friend and fellow miner. I’d met them a couple of days earlier as they manned a picket line in the Alabama twilight after working full shifts at jobs they had taken to pay the bills. The fervor of the strike’s early days had given way to an unhappy few manning their posts like sentries in a long-abandoned war.

Gardner makes his friend a drink and waits for him to take a sip. “They wanted to bring in workers who had no loyalty to the union and no loyalty to the rest of us,” says Gardner.

Mudd prods his friend to tell me a story of what happens when trust isn’t present. They both agree that safety can only come when miners know their fellow miners and their movements.

“When you work with someone for a long time, you can just communicate with a look,” George tells me. “My partner could just move his hand one way and I knew what it meant.”

George works in the mine as a shear operator, manning a giant machine that strips coal from the ground. Above the machine is a roof of sorts called a shield that protects miners from dislodged coal falling on them. In 2018, George reported to work and noticed that his regular partner wasn’t there. He took the elevator down to his spot and began his shift safety check. The shield moves up and down to provide the most protection but was stuck that day. George moved in to inspect the shear, but he didn’t realize his partner was trying to fix the shield. He didn’t know his new partner was manipulating the shield’s gears. Suddenly, the shield came crashing down on him, splitting his helmet in two.

The force of the blow snapped his femur and smashed his internal organs. He drifted in and out of consciousness, coming to on a stretcher as he hit the surface. A helicopter and ambulance were waiting for him.

He spent nine days on heart and lung machines before he stabilized. He pulls out his phone and shows me a photo of him flat on a gurney but flipped up. “This is when I begged them after two weeks to let me see the sky,” he tells me in a soft voice. “They wheeled me over to a window so I could see outside.”

He was released after two months and returned to work eight months later. He got married in 2021, and he and his wife now have a baby girl. But he will never be whole again. He walks with a limp from a drop foot caused by permanent nerve damage from the accident.

Warrior Met has taken something from him, he says. Going back to work without a decent raise would mean he was giving up on himself. Gardner was the best man at his wedding and knew what his friend had to do so he could get back to working at the mine. He gets George a fresh beer and just shakes his head.

“Warrior Met kept saying, ‘Work with us. Work with us, and if you do, we’ll take care of you.’ ”

Gardner then pours everyone a shot and we toast the coming new year.

“This ain’t my definition of taking care of us.”

UMWA PRESIDENT CECIL ROBERTS estimates the miners’ wage and benefits givebacks saved Warrior Met more than a billion dollars between 2016 and 2021. Warrior Met CEO Walter Scheller admitted in the company’s 2017 annual report that the givebacks were a boon to the company’s profits: “By combining the highest price realizations of all U.S. met coal producers together with our exceptionally low-cost structure, we believe Warrior has among the highest margins in the industry.”

Larry Spencer has been negotiating union contracts for two decades but has never seen a negotiation like this.

“What we kept hearing from Warrior was that if you help us now, we’ll make it right down the road,” says Spencer, who was part of the 2016 negotiations. “It never happened.”

Instead, the miners claim Warrior Met offered a five percent raise. At that trajectory, the Brookwood miners would not return to their 2016 $28-an-hour rate until 2036. More than 95 percent of the Brookwood miners voted to reject Warrior Met’s offer.

Warrior Met’s replacement workers were given sign-on bonuses and days off that the Brookwood miners say they never received. You can imagine how well that went over with the Brookwood strikers. They broke car windows and bloodied the faces of strikebreakers trying to get to the mine.

Then again, there were credible reports of strikers being hit by cars on two occasions. Most of the Alabama public only heard about the miners’ rage. This was not an accident. Warrior Met hired the public relations firm Sitrick and Co., longtime practitioners of the dark art of crisis management. Together, they posted on YouTube and compiled video packets for local television stations emphasizing the miners’ violence against the replacement workers.

Warrior Met has other strong allies, particularly Alabama’s governor, Kay Ivey, who instructed the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency back in 2021 to provide armed escorts for the strikebreakers entering and leaving the mines, proclaiming everyone has a right to get to work safely. Then, a circuit court judge issued a restraining order preventing the strikers from protesting outside multiple entrances and exits to the mine.

The order was eventually lifted, but tensions flared again when a gas pipeline exploded on Warrior Met property in March 2022. The company immediately blamed the strikers but didn’t offer any evidence. (The UMWA has repeatedly denounced violence as a tactic.)

Warrior Met took its case to the National Labor Relations Board and calculated the unruly strikers had cost the company $13.3 million in repairs and security costs. The NLRB agreed and issued an order for the UMWA to pay the full $13.3 million. This outrageous amount made the union responsible for all the expenses of a strike, an unprecedented move. It was reduced to $400,000 upon appeal, but the initial ruling had a chilling impact on strike activities.

The union has tried other tactics. In December, four white buses brought 30 strike supporters to the posh Hoover, Alabama, neighborhood of a Warrior Met executive for a silent candlelight vigil. It didn’t last long. The protesters were met by the screaming sirens of multiple police cars. The vigil was broken up, and the protesters were detained until they handed over identification and the cops took down their names. Their protest lasted 18 minutes.

SPENCER SUGGESTED I stay at the Embassy Suites in Tuscaloosa, about a 30-minute drive from the Brookwood Mine. He tells me why when we sit down for coffee in the hotel’s cavernous lobby.

“Nice place, right?” says Spencer with a sad smile. He’s wearing a UMWA camouflage T-shirt. “I’ve suggested to Warrior Met that we meet here in one of the conference rooms, and they always refuse.”

I ask Spencer when the last time was he’d had an in-person negotiation with Warrior Met officials. His answer is succinct.

“Never.”

I think that maybe I heard him wrong. This was the longest strike in Alabama history; surely there had been at least some bad-faith in-person negotiations.

“No,” Spencer says. “At first, they said it was because of Covid, but now that Covid is under control they still come up with excuses. I’ve never met with these folks in person.” He takes a pull on his coffee. “That tells me they are not serious about settling this.”

You either support workers or you don’t. We supported Starbucks and Amazon. If you’re for workers, you have to support all the workers.

Over the past two years, some strikers have crossed the picket lines. Some have started over at other mines, forfeiting their seniority. That isn’t an option for some workers. I talk with three fiftyish workers in a cramped union office that smells of bad coffee and cigarettes. After 20 or more years, their seniority had rewarded them with aboveground jobs, delivering parts and equipment around the complex. One of them admits he was out of options:

“I can’t go to another place and start over; my body just couldn’t take being down in the mine 12 hours a day.”

The UMWA has not brought a new proposal to the striking miners in the 23 months since the strike started. The union’s official position is that there’s no reason to since the Warrior Met proposal hasn’t appreciably changed.

I ask the three men what would happen if the same offer was brought back to the miners now. “I think it’s 50-50 that it would pass,” one says. The other two nod. “People are getting desperate.”

Meanwhile, Warrior Met announced a net profit of $98.4 million for the third quarter of 2022, the most recent reporting period. This was a $60 million uptick from 2021.

A FEW DAYS AFTER the Christmas party, Haeden Wright is bagging groceries at an old union hall that has been converted into a pantry since the strike began. Every two weeks, the pantry opens, and miners’ families can come in and get free diapers, formula, and other grocery staples to help them get by. This week there’s the added bonus of all the makings of a Christmas dinner: stuffing, cornbread mix, and a gift certificate for a ham.

Wright and other volunteers load the miners up with two bags apiece. They also let them pick out some essentials: toothpaste, deodorant, shampoo.

“We had to stop giving out toiletries for a while,” Wright says. “Formula cost was going through the roof, and we didn’t have the money.”

A young miner named Adam walks in, his eyes to the floor. He just split with his wife and has three kids to feed. You can tell this is the first time he has had to ask for help, and you can see the pain across his face. Wright and the other volunteers give him a smile and an affectionate grab of the arm.

“We’re a family, you need to know that it’s OK to ask for help,” Wright says.

She knows this world. Her daddy was a miner, and her husband, Braxton, has worked at the Brookwood Mine for nearly two decades. “In the first six weeks of a strike, it’s a party and you’re pissing vinegar,” says Wright as the families arrive. She is a schoolteacher, and she and Braxton have two kids, one who is scampering around the pantry. “Starting around two months, you start realizing, dang, I got to pay bills. And there’s bills that you can’t pay, and you have to start asking for help.”

It is happening to the Wrights as we speak. Last year, the heat went out on the lower level of their three-story house. This year, it stopped pumping out heat on the top floor. Now, the family huddles on the middle floor with a space heater, and the temperature dropped into the teens on Christmas Eve. Wright gives a resigned shrug.

“It’s $6,000 that we don’t have right now. We’re getting by, just like everyone else.”

She excuses herself. There’s more work to be done. The sun falls, and miners and their families continue to stream inside. Some are doing OK and crack jokes. Others are barely still alive. (Miners tell me there have been suicides and divorces over the long winter of the past two years.)

The UMWA tried to break the log jam with a risky move on February 15. UMWA President Cecil E. Roberts announced at a union meeting that he was ordering Brookwood miners back to work, effective on March 2. The struggle for a new contract, he said, would continue while they got back to work. He talked of how the miners had fought Warrior Met to a draw, an overly optimistic assessment of the situation. Some in attendance thought the move was capitulation, a sign that the previous 23 months had all been for nothing. Some saw it as simply facing reality.

That day he sent Warrior Met Coal CEO Walt Scheller a legal document called an “unconditional return to work” offer. Some local media reports suggested that the strike had been settled. This wasn’t true. Roberts’ statement came with some strings attached. He insisted the miners would only go back if they were paid the same rate that the strikebreakers were currently making.

“The status quo is not good for our members and their families,” Roberts said. “The company continues to pay the temporary replacement workers in its mines significant wages and bonuses up to $2,000 more per month than it has offered to pay our members at the bargaining table. If it is going to pay that kind of money, we believe it should be going to Alabama miners and their families, not those coming from out-of-state.”

The miners’ strategy had another purpose: If Warrior Met didn’t accept the workers back and come to the table, the union could claim their workers were being locked out, potentially making Warrior Met liable for significant damages including back wages.

Trending

Trump Used $10 Million of Donor Money to Pay His Personal Legal Bills

Trump Defends Putin as Biden Visits War-Torn Ukraine

She Built a Following as Taylor Swift's Doppelgänger. Then the Swifties Came After Her

An Attempt to Subpoena Drake at His Mansion for the XXXTentacion Trial Did Not Go Well

Warrior Met responded a few days later, but no details emerged about the terms or if an agreement was imminent. (Some miners suggested a sticking point was that Warrior Met did not want to accept over 40 miners back who the company said had been cited for violence during the strike, a condition the union would vigorously oppose).

In the interim, the miners are simply trying to survive. Marcus George just took a job at another union mine in Alabama. This keeps him in good standing with the UMWA, but he is starting over as a rookie, his seniority gone. He tells me he still wants to return to Brookwood when the strike is settled. Meanwhile, his buddy is standing firm.

“I don’t want to get something that just gets us by,” Mudd Gardner tells me. “We want something that sets a standard that miners will look up to for years.”

He pauses for a moment.

“We want to leave a legacy.”

I do not know if Gardner and the other Brookwood miners are brave or the last casualties in a war that is already lost.

Best of Rolling Stone