Last Salem 'Witch' Pardoned 329 Years After She Was Sentenced to Death

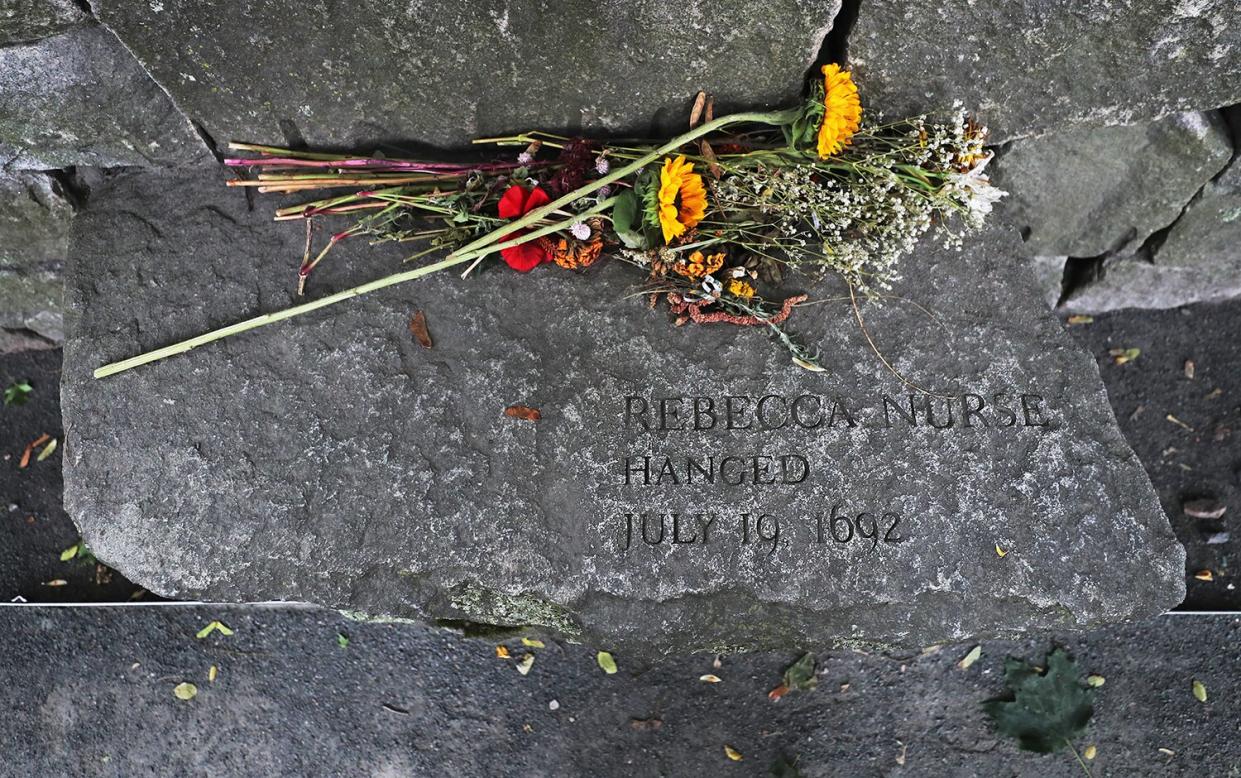

Jim Davis/The Boston Globe via Getty

The last Salem of the "witches" has officially been pardoned.

On Thursday, Massachusetts lawmakers formally exonerated Elizabeth Johnson Jr., who was convicted of witchcraft and sentenced to death in 1693 at the height of the Salem Witch Trials.

Though Johnson was never actually executed, her pardon 329 years later means her name has officially been cleared.

According to the AP, lawmakers agreed to reconsider her case last year after a curious eighth-grade civics class at North Andover Middle School took up her cause and researched the legislative steps needed to clear her name.

Subsequent action was later taken by state Sen. Diana DiZoglio, a Democrat from Methuen, who brought up the concern and had the motion passed.

In DiZoglio's senate floor speech, she shared Johnson's full story. After being convicted but not sentenced in 1693, the witch trials come to an end in 1702. Consequently, "Those who had been convicted but not executed started petitioning to have their convictions overturned and by the end of 1711 all of them had been exonerated, all except for one," DiZoglio detailed.

Sen. DiZoglio took to social media to social media after the motion passed to celebrate the moment: "The @MA_Senate has PASSED legislation to clear the name of "Last Witch" Elizabeth Johnson Jr.," the Senator wrote. "This wouldn't have been possible without @NAMiddle teacher Carrie LaPierre and her amazing civics class, whose hard work was essential to its filing."

The @MA_Senate has PASSED legislation to clear the name of “Last Witch” Elizabeth Johnson Jr. This wouldn’t have been possible without @NAMiddle teacher Carrie LaPierre and her amazing civics class, whose hard work was essential to its filing. #mapoli https://t.co/QPKHCYznrR pic.twitter.com/VbmwruR7yR

— State Senator Diana DiZoglio (@SenatorDiZoglio) May 26, 2022

In a statement to AP, North Andover teacher LaPierre — whose students championed the legislation — praised the youngsters for taking on "the long-overlooked issue of justice for this wrongly convicted woman."

"Passing this legislation will be incredibly impactful on their understanding of how important it is to stand up for people who cannot advocate for themselves and how strong of a voice they actually have," she said to the outlet.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from juicy celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

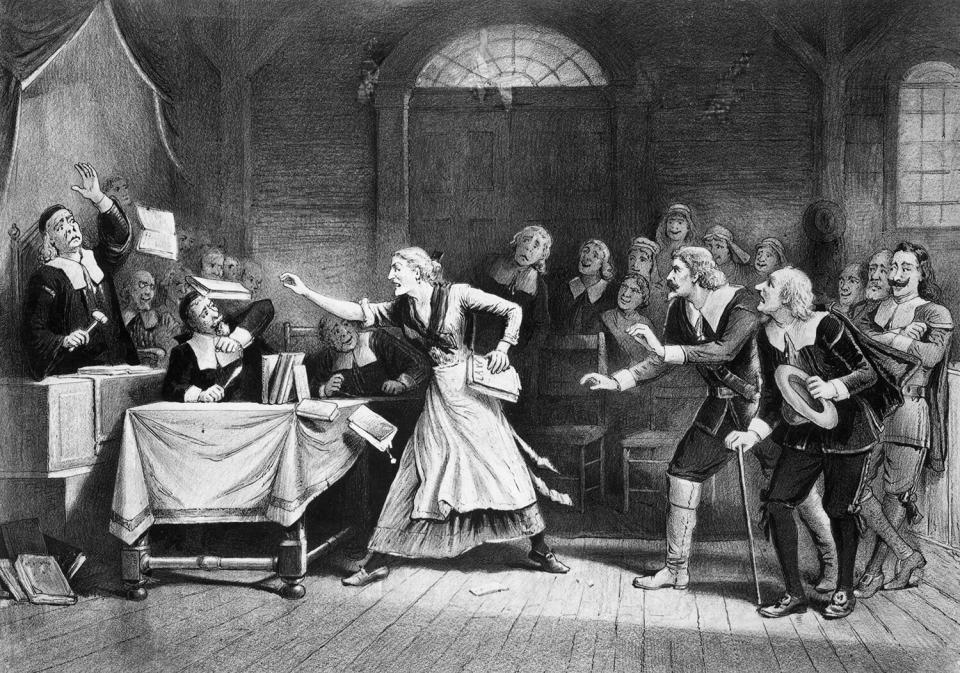

Getty

Beginning in 1692, dozens of women were hanged for witchcraft and hundreds more were accused of being "witches" at the trials in Salem. The deadly period was stoked by superstition, fear of disease and strangers, scapegoating and petty jealousies.

According to CBS, Johnson was 22 when she was caught up in the hysteria of the witch trials and sentenced to death.

In the more than three centuries that have ensued, dozens of suspects officially were cleared, including Johnson's own mother, the daughter of a minister whose conviction eventually was reversed. Unlike others wrongfully accused, Johnson was not married and never had children so she had no descendants to act on her behalf.

"Elizabeth's story and struggle continue to greatly resonate today," DiZoglio said to CBS. "While we've come a long way since the horrors of the witch trials, women today still all too often find their rights challenged and concerns dismissed."