Larry Charles Released the Movie He Set Out to Make: “That’s a Miracle in Hollywood”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

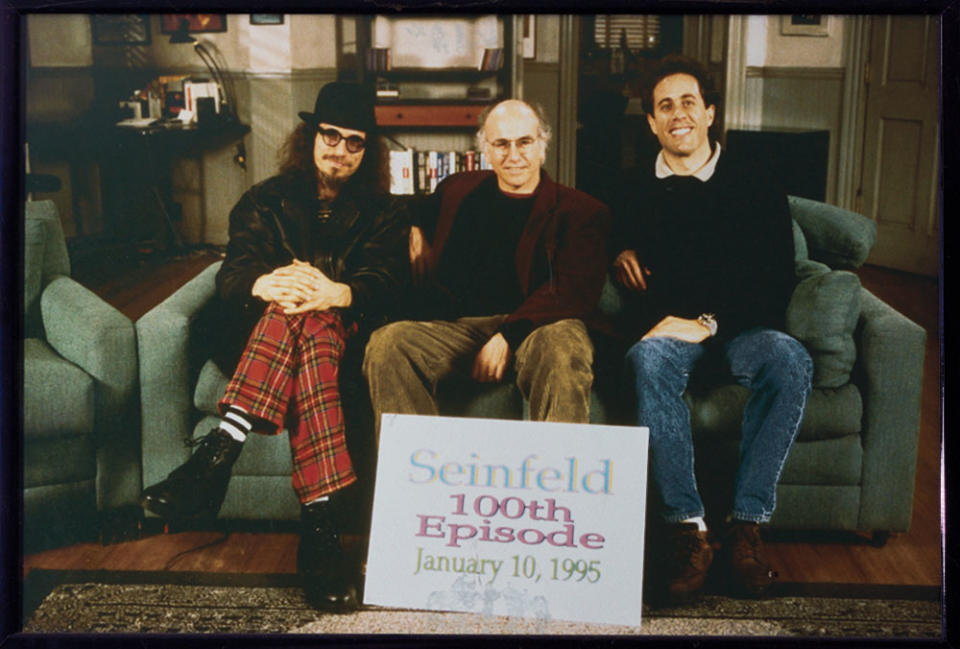

Larry Charles’ résumé is all over the place. As a writer, he penned some of Seinfeld’s most memorable episodes (see: “The Library”). As a TV director, he skewered his industry with Curb Your Enthusiasm and Entourage. As a filmmaker, he embraced mockumentary with Borat and Brüno. But his latest entry, by his own admission, might be his most unhinged to date. He just released Dicks: The Musical, a hard-R spoof of The Parent Trap featuring telepathic sewer creatures, a disembodied CGI vagina and Megan Thee Stallion walking men on leashes like dogs. “I don’t have a legacy or body of work or anything like that, so I don’t think about stuff like that,” the Dicks director explained on the eve of its Oct. 6 theatrical launch. “I never know what I’m doing next.”

Charles is about as unassuming as a comedy icon can be, having spent four decades collaborating with the likes of Larry David, Jerry Seinfeld, Sacha Baron Cohen and even Kanye West. Speaking from the Malibu home he shares with his wife, the youngest of his five children and two dogs, he can sometimes seem like just another bohemian grandpa — albeit one with a bank of Hollywood stories that often sound too wild to believe.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

After you made Army of One in 2016, you swore off features. Why?

I felt betrayed. It was a small-budget movie. I had gotten Nicolas Cage to go along with me. We were very clear about what we wanted. We shot it. It was good. Then, the producers — Bob Weinstein was one of them — turned on it. It was every horror story you hear about what can happen to a movie. I was kicked out of the editing room. They removed my music. They changed the ending. And for what? It didn’t even make any money. I couldn’t see myself getting involved in that again, with such a lack of trust.

What changed?

I learned a lot on Dangerous World of Comedy, which I did for Netflix. I interviewed people in comedy in countries like Liberia and Somalia who were making stuff that was spontaneous, essential, impactful. That inspired me. Then this came along. I’m back in the movie world, but it’s a radical queer comedy for A24. Not Bob Weinstein. The movie we set out to make is the one onscreen. That’s a miracle in Hollywood.

Were you attached when it was at Fox? I imagine the Disney merger killed its chances there.

No, I got involved around the time A24 did. Peter Chernin is a producer, so that’s the reason it first wound up at Fox. It wasn’t a good fit there, although Fox did do Borat. I sat next to Rupert Murdoch at the Golden Globes.

What did you talk about?

Rupert, he’s a raconteur. You can talk about anything with him. We were just bullshitting, making each other laugh. That made it a much more pleasant evening. But when you work with Sacha, you’re forced to meet people who are diametrically opposed to you.

At the beginning of your career in the 1970s, you sold jokes outside the Comedy Store. Do you remember any you were underpaid for?

They were only sold on spec! If they did well with the audience, I would get 10 bucks. But I never thought about money or career. I thought about being in show business, not even knowing what that meant. Eventually comedians started liking my jokes, and I got paid more. But I was still a parking valet back then.

Ever valet for anyone famous?

David Steinberg, the comedian. I don’t know if it was him or his wife, but they used to leave roaches in the ashtray. Parking valets could steal pot because no one could report it. I got friendly with David and eventually wound up writing for him. But, before that, we’d steal all his roaches and smoke them after work.

Your stint writing for Arsenio Hall infamously ended with a six-month stretch when none of your jokes made it to air. What did you learn?

That was rock bottom for me. Arsenio was a great guy, and he loved my jokes. But, being a Black man on TV, people do not realize the pressure he was under. The death threats! No one was online yet, so it was stacks and stacks of violent hate mail. My jokes were hard-edged — and, after a while, he retreated to safer material. I just had a baby, convinced I was about to get fired and would never work again, so I went outside at Paramount and looked up at the sky, like, “What am I going to do!?” Jack Nicholson, who was filming The Two Jakes, drove by very slowly in his Mercedes convertible, wearing the Lakers hat and the sunglasses, and we look at each other and just start laughing. I think, “He knows this is all just a game. Don’t take it so seriously.” I got fired, and the next day, I got offered the job on Seinfeld.

Any particularly memorable network notes from working in broadcast in the ‘90s?

The most memorable, ironically, was for the Seinfeld episode “The Contest.” There were no notes. Larry David and Jerry had done such a clever job that there were no bad words or no bad gestures even though it was graphically about masturbation. The sensors were caught by surprise.

What was the most noted episode while you were there?

I had episodes that were so noted that they got killed before they got produced. It’d be a big note like, “We just can’t do this.” We used to have gigantic arguments, not so much about the censoring, but about what a sitcom was. Castle Rock and NBC, they had a certain preconceived notion based on Cheers. “The Chinese Restaurant” was maybe the most famous of those. Larry basically wrote a [Samuel] Beckett play about people waiting for a table. The network was like, “Something has to happen!” When the show finally clicked [with viewers], all those notes went away.

You and Larry David made the doc series The Larry David Story — which Larry famously pulled one day before it was set to premiere in 2022, saying he preferred to air a live performance. Will we ever see it?

You’d have to ask him. It’s really good. It’s Larry as I’ve known him for almost 40 years. I wish it would come out, but I have no control over it — like with most things. I live in chaos, man.

You directed the Kanye West comedy pilot that never went at HBO. What happened there?

Well, that was a very different Kanye than today. We hit it off. I considered him a friend for quite a long time. The first thing he ever said to me was, “I’m the Black Larry David.” Strangely enough, he was always apologizing — which is very Larry David, because he’s always putting his foot in his mouth. It was like a day in the life of Kanye, and it was super fun to shoot. Very spontaneous. For whatever reason, HBO decided not to go forward.

Did you have a hard time reconciling the Kanye you knew with the antisemitism comments he made this year?

There were times when I was extremely distressed. I’ve seen this before from John Belushi. These people become golden gooses for their people around them, and nobody’s being honest with them, and nobody’s getting them the help they might need. When I hear him going off like that or supporting Trump or running for president himself, I feel like it’s crazy content. But I also feel compassion, knowing that he wasn’t like that before.

Ari Emanuel repped you when you were working on Entourage. What were your conversations about Ari Gold, the character, like?

Once you get into the head of Emanuel, it’s a very easy character to write. And Jeremy Piven’s interpretation was perfect. He was able to make it even more aggro. Our Emanuel, he’s somebody who gets what he wants. It’s very easy to make fun of people like that.

With Dangerous World of Comedy, you interviewed a cannibal warlord in Liberia about his love of Norman Lear sitcoms. Were you at all scarred by that experience?

I was just thinking the other day that I did have some PTSD. There were times in Somalia — I mean, first of all, what am I doing in Somalia? — where I was in an armored vehicle in the middle of Mogadishu, surrounded by guys with machine guns. You didn’t know what side anybody’s on, and bombs were constantly going off. In those situations, I become totally calm, But when I got home, I realized how scary it was.

When did you feel the most at risk in your mockumentary features?

Brüno was the most dangerous movie because we underestimated the amount of homophobia in the world. Sacha, if he was dressed up as Brüno — and this did not happen with Borat — people would just jostle and slap him. I was constantly having to back people up, however I could. In Jerusalem, Sacha wore these Hasidic hot pants, and they threw rocks at him. We all dispersed, and I was cornered by all these angry people with rocks over their heads. I’m from Brooklyn and basically called their bluff. I got lucky that they didn’t just kick my ass.

Specifically, you grew up in Trump Village — a Coney Island apartment complex developed by one former president’s father. How did that inform your childhood?

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a picture of Fred Trump, but he was the devil incarnate. Donald would come around, when he was 14 years old. It was lower-income housing, so everybody moved in at the same time and there was this demographic explosion. There was a hierarchical, violent pecking order like a prison or Lord of the Flies.

Who’s a comic voice from your generation who you feel still hasn’t gotten their proper due?

Albert Brooks. He’s a genius and a major influence on a lot of comedy people — his early standup, prose pieces, albums and movies. He’s singular. I’m sad that he doesn’t work more, and I’m surprised that he’s not in that pantheon. He deserves to be there.

You’re a DGA and WGA member. Were your biggest gripes resolved in the new deals?

No, but I’m glad it’s resolved. I’ve never voted to ratify any of these contracts. I always feel they’re compromises. The system itself is broken. It’s analogous to the government. Broken. Are we courageous enough to change the system? Because little stopgaps will not fix it. The corporations that run the studios, their job is to be greedy. Unless we change the value system, then we’re going to run into these problems forever until it runs aground.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

A version of this story first appeared in the Oct. 11 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter