L.A. Has Its Own History of Anti-Drag Laws

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Since Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed a bill that would ban drag performers from staging “adult-oriented performances that are harmful to minors,” at least 14 states have proposed similar laws. Such legislation, separate but related to a broader skepticism and antagonism among Republican lawmakers toward trans-affirming care, taps into a centuries-long history in the U.S. — and in Los Angeles in particular — of government action against gender nonconformity.

In the nineteenth century in the United States, ordinances criminalizing “cross-dressing” existed at city and state levels. Initially, law enforcement used anti-masquerading laws to enforce the restriction of gender divergence. “This was part of a larger effort to really begin regulating people’s gender expression,: explains Dr. Eric Cervini, a Pulitzer finalist and historian focusing on LGBTQ+ politics. “These laws were originally constructed to prevent people from disguising themselves and rioting.”

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Fox Settles Defamation Case Brought by Venezuelan Businessman

Jon Stewart, Jimmy Fallon and Stephen Colbert React to Absurdity of Trump Arraignment and Arrest

Laws specifically prohibiting men dressing as women and women dressing as men cropped up as the nineteenth century progressed. Ordinance 5022 in 1898 brought these explicit restrictions to Los Angeles.

Lillian Faderman, a premier scholar of the city’s queer history and co-author of Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians, traces the legislation to an annual bacchanal staged in L.A. in the early 1890s: “The last day of the weeklong fiesta was All Souls Night, kind of like Mardi Gras. People would go wild — that made some residents and visitors to early Los Angeles uncomfortable. That was the beginning of laws against cross-dressing in L.A. Five years later, that became Ordinance 5022.”

The ordinance was selectively enforced, as drag performances were a popular and highly lucrative source of entertainment in the city at the turn of the century. Faderman mentions a few choice stars and locales who assumed the spotlight over the next several decades: performers like Julian Eltinge and Sir Lady Java and famed drag and gay venues like The Orpheum, Jimmy’s Backyard, and B.B.B.’s Cellar. “There was vaudeville that often headlined cross-dressing acts,” Faderman explains. “Some of those cross-dressers were the highest paid in the vaudeville business. There was all this notion that cross-dressing was for entertainment. And so in pre-Hayes [the production code banning “amoral” themes in film] Hollywood, cross-dressing on the screen was very well received. Even [Marlene] Dietrich, famously, in Morocco [1930]. This was family entertainment — nothing underground about it. But at the same time these laws existed. They were just frequently overlooked.”

Instead, these rulings were used to target actual gender nonconforming individuals in tandem with police raids on spaces perceived to be pick-up joints for gay sex. “If you were a straight guy trying to make a straight audience laugh by putting on a woman’s dress, that was perfectly acceptable,” says Cervini. “But if you were a trans or gender nonconforming person just walking down the street, that was seen as a threat to society, and that would have landed you in jail.”

After the crackdown on queer spaces of the 1950s — and the terrifying regime of the extremely homophobic LAPD chief Ed Davis (nicknamed “Crazy Ed”) in the 70s — androgynous fashion trends in the latter half of the century helped to dissipate the enforcement of laws criminalizing gender nonconforming people: “It was particularly hippie style [that made it] a little harder to say that you couldn’t wear the apparel of the opposite sex,” Faderman says.

“These sorts of laws [often] stayed on the books, they were technically never repealed,” adds Cervini. “They just stopped being enforced. That’s true of sodomy laws, of so many different laws in this country.” Trans activist and scholar Alok Vaid-Menon adds that these laws targeted “anyone who defie[d] what society thinks a man or woman should look like. It’s always been about making the majority of people align into gender norms.”

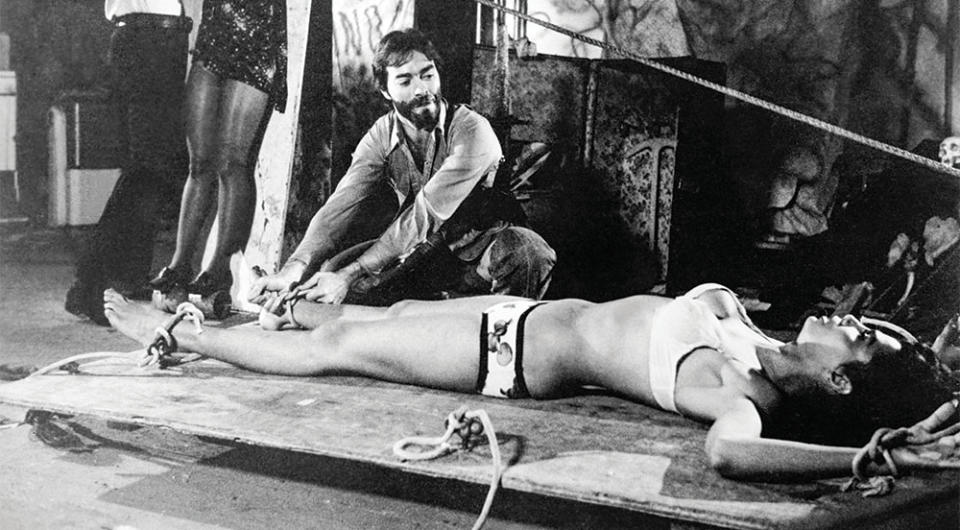

But not all. In 1967, L.A. enacted Rule No. 9, an evolution of Ordinance 5022 that outlawed drag performances without police permission. That year, after being barred from performing her act at Redd Foxx’s club on La Cienega, the transgender performer Sir Lady Java challenged the rule in court alongside the ACLU, arguing it violated her right to work. Thanks in large part to her stand, Rule No. 9 was repealed in 1969.

Despite the swarm of new state legislation, Faderman maintains hope: “I came out in the 1950s, and those were certainly the worst times ever. Boys would be regularly raided, and to the psychiatric profession, we were all crazy, because we were in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. To the police, we were all presumptive criminals. [But] I’ve seen how we organized and we fought and how things became so much better. I guess I’m hopeful. We have so many allies.”

Remembering the attacks of the past on the LGBTQ community is a key tool in battling for protections in the future, Cervini argues. “The effort to persecute gender nonconforming people goes back hundreds, if not thousands, of years. This phenomenon that we’re witnessing of those in power, who feel that their power is ebbing … they have to rely on some sort of scapegoat. That was true of the Catholic Church in the 11th century, and it’s true of the Republican Party now, in 2023.”

A version of this story first appeared in the April 12 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter