“Knowing Shit from Shinola”: An Oral History of The Jerk

The post “Knowing Shit from Shinola”: An Oral History of The Jerk appeared first on Consequence of Sound.

“I was born a poor black child…”

This may be one of the funniest lines ever committed to film, and it’s spoken within the first minute of The Jerk. Yet that one simple phrase subverts any expectations for Carl Reiner’s 1979 classic. As you see Navin R. Johnson (Steve Martin), sitting among bums, there’s this air of woe that is simply pathetic. You can’t possibly laugh at a man like this. It’s too sad to be funny. And then out comes that line, and everything changes.

The Jerk hit theaters 40 years ago this month, changing the game for Hollywood comedies, while also creating a bigger star out of Martin. Nobody knew it at the time, though. They were just trying to make a funny movie, a biting satire on the Beverly Hills lifestyle called Easy Money, and that’s it. Of course, Reiner and his team eventually took a much-needed detour, exploring a far more absurdist route.

In commemoration of its landmark anniversary, Consequence of Sound spoke to screenwriters Carl Gottlieb and Michael Elias in addition to director Carl Reiner to backtrack through that groundbreaking journey. Together, they shared some of their favorite memories making the film, the hurdles they needed to leap over in the process, and how it really did start out with that whopper of a line.

CARL GOTTLIEB (SCREENWRITER): There was no idea. We sat there everyday. We had a nice little office in the writers building right on the Paramount lot with a couple new pencils and yellow pads and we’d go into work every morning and look at each other and say “Well, what about…” And then a couple of weeks went by and we didn’t have anything.

And then Steve one day said, “Y’know, there’s a line in my act that always gets a laugh, even if the act isn’t doing that well.” I said “Well, what’s the line?” He says “I was born a poor black child.” So, that landed in the room with significant impact. And we said, “Wow. But what if you were? What would that be like? Steve Martin as a poor black child?”

In April of 1977, Steve Martin played a sold-out show at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in L.A. One of the members of the audience was David Picker, who was a higher up executive at Paramount at the time. Witnessing Martin’s rabid fan-base, it occurred to him that there was something going on there. From there, he knew he wanted to bring the comic into Paramount, who signed Martin to a two-picture deal.

GOTTLIEB: Steve was still an unknown quantity on film, and that was the reason for The Absent Minded Waiter short, which I directed, and starred Buck Henry and Terri Garr. The theory, and this was really good thinking by David Picker, was “We do it as a short, we attach it to one of our big pictures, we give it to our exhibitors for nothing. But the film audience gets to see Steve Martin on the big screen and they will see his star quality and that will build an audience for him.”

We had a first draft that was pretty good. We’re working away, and we write a first draft. And in the meantime, Paramount has a change of regime and Barry Diller and Mike Eisner are brought over from ABC to be in charge of production at Paramount. Like what usually happens in Hollywood when a new team comes in, they scrap all the old projects and they want to develop their own slate, so they get credit for it.

So, they kind of decided that they didn’t want to be in the Steve Martin business. So Steve’s management went to Paramount and said, “Look, you owe us for two movies. Whether you want to release a Steve Martin movie or not, you owe us for another screenplay after this one. So, tell you what we’ll do. You give us Absent Minded Waiter, free and clear, for our own use, and we’ll take the script, pitch it some place else, and you can make whatever movies you want without us.” And Paramount said, “Okay.”

I was unavailable to do the next rewrite. I did the first couple of drafts with Steve. And we had failed to move the powers that be at Paramount and we were going over to another studio. So I wasn’t around to do the rewrite. So they got another comedian friend of Steve’s named Michael Elias.

MICHAEL ELIAS (SCREENWRITER): Steve and I wrote together on Pat Paulsen’s Half a Comedy Hour. We were on staff and we became friends and then I started writing material with Steve for his comedy act. So Steve invited me to Aspen, where he was living then. And Universal rented a little house for me, not far from Steve’s house, and it was a month of skiing and writing. We would meet and have breakfast, we’d ski for a while, we’d come back, we’d write, have dinner, and write some more, and play chess. And we just did that for a month every day.

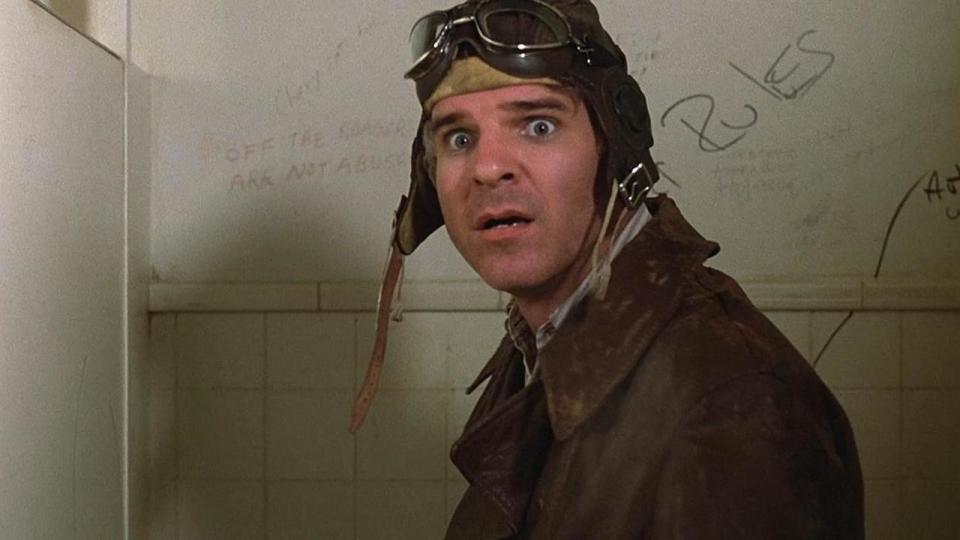

Steve Martin in The Jerk (Universal)

With Michael Elias and Steve Martin working on a new draft, the original script went through substantial changes, particularly the second half of the film.

GOTTLIEB: The whole first half of the movie, where he leaves from his home life in the shack in Mississippi Delta from there to hitting the road to working at the carnival and developing the opticgrab device, that’s pretty much me and Steve. And a lot of the stuff with Bernadette [Peters] and a lot of the stuff with life and a lot of money that was pretty much Michael and Steve and Carl Reiner.

ELIAS: I think we were influenced by Nathaniel West’s The Dismantling of Lemuel Pitkin as a model. It’s kind of spoofing the Dale Carnegie success story. Rags to riches. This is a great rags to riches to rags and back again. And riches turns out to be family. That’s the wonderful thing about it, also. He leaves his family to find his fortune and winds up back with his family. And everybody’s happily ever after.

Steve Martin in The Jerk (Universal)

With the script now completed, it was time to bring on a director.

GOTTLIEB: I would have liked to have directed it. Had we stayed on track at Paramount, I probably would have directed it. But it would have been a substantially different movie, because Michael Elias contributed a tremendous amount to the film.

ELIAS: At one point, Mike Nichols was interested in directing it, but he dropped out, and the next choice was Carl Reiner. And Carl was great. There couldn’t have been anybody better to direct that movie, that’s for sure.

CARL REINER (DIRECTOR): Well they came to me and they already decided that they were going to make the film. And none of them were filmmakers, so I sort of guided the whole film as a pro filmmaker. But Steve was a genius waiting to be recognized as a performer. He and I used to travel together, to go to the set every day, and, one day, we found a piece of gold.

It was the day his father was going to send him out into the world to find his fortune, but he wasn’t sure he was ready. And this is what we found on the way to work that day. He’s walking and he says to his son, “You stepped in shit.” “What’d I do?” “You stepped in shit. You see that on your heal?” “Yeah.” “That’s shit.” And there was a phrase in those days, “You don’t know shit from shinola.”

So, [Steve] takes a little box out of his pocket and says, “And this, my son, is Shinola. What’s that on the floor?” “That’s shit.” “And what’s this?” “Shinola.” “That’s right. You now know shit from Shinola. You’re ready to go out into the world.”

GOTTLIEB: Steve’s comic sensibility informed the whole film, and Carl Reiner, being a really skillful comedian and director. He wrote on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, arguably the most sophisticated comedy to come out of television in the last 70 years. So that collaboration produced a lot of great jokes. There was the water cooler that has crystal glasses instead of paper cups. That was a Carl Reiner joke.

REINER: Once we did this film together, we did three after that, so you realize we were on the same page every day and we understood each other and it just flew out of us.

ELIAS: There was a scene we didn’t shoot, where they meet. I think they meet at the carnival now. But we wrote a scene where [Steve] goes to a diner and she’s a waitress and she hands him a menu and says, “What would you like?” And he says, “I’ll have a small orange juice, a large orange juice, a small grapefruit juice, a large grapefruit juice, a small melon, a half a melon, I’ll have fried eggs, I’ll have fried eggs with bacon. And he reads the whole menu, and she keeps writing. And she writes and writes. And as she’s writing and he’s going through the entire menu, they’re falling in love.

GOTTLIEB: We had a great joke where, at one point, Steve and Bernadette are living in the big house and they’re trying to be accepted by Beverly Hills society. And they’re having a lot of trouble and they’re being blocked at every step by one of these Rodeo Drive ladies who is very active in civic affairs and very Beverly Hills and she doesn’t want to give them the time of day. They’re new money and all that.

And as the story progresses, Bernadette says “We have all the money you could ever want. What do you want that you never had?” Navin says, “Well, I’d like a thousand dollar a night call girl. I can’t imagine what that’s like.” She says, “If that’s what you want, honey, you can have that.” So they arrange for a thousand dollar a night call girl to show up, and it’s the Beverly Hills lady, which we thought was a comment on social justice.

ELIAS: I was involved in location scouting. I remember the first time we went to the Sheik’s house [the mansion Navin lives in], because that was unbelievable. That’s the way it really looked. That house was just the way it was. It was owned by a Saudi prince’s son, and his son was going to UCLA and lived in this house, so, of course, the house was designed by a college freshman with 40 billion dollars to spend.

GOTTLIEB: I remember walking through it, looking at the billiard room and the clamshell bathtub and all the features. I said to the prop man, “Where did you find this stuff?” And the guy would keep saying, “It was here.”

ELIAS: The guy put up nude statues that hung out by the fence outside and he painted them. And the neighbors, this is in the middle of Beverly Hills, were going bat shit, man. They couldn’t stand it. They burnt it down a few years later. And I think the kid was recalled by his father back to Saudi Arabia for embarrassing the family.

Click ahead to read about the legacy of The Jerk, whether its creators feel like it could be made today, and how it tickled the funny bone of one legendary filmmaker…

“Knowing Shit from Shinola”: An Oral History of The Jerk

Michael Roffman

Popular Posts