“Killers of the Flower Moon ”author David Grann on the film's message: 'This is still living history'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

David Grann is no stranger to having his writing adapted for film. The popular author and New Yorker staff writer has become a staple on the New York Times non-fiction bestseller list, and his writing has inspired films including The Lost City of Z, The Old Man and the Gun, and Trial By Fire. Now, his work is reaching a new audience, with Martin Scorsese adapting his book Killers of the Flower Moon (in theaters now).

When Grann first published his book in 2017, it shined new light on an oft-overlooked chapter in American history: the Osage reign of terror in 1920s Oklahoma, when a group of white settlers targeted and systematically murdered wealthy Osage people. Lily Gladstone stars as Osage woman Mollie Burkhart, with Leonardo DiCaprio as her white husband Ernest and Robert De Niro as Ernest's powerful uncle William "King" Hale.

Grann first started researching in 2012, and he spent years conducting interviews and meeting with members of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma. His book chronicles the early days of the FBI and how the bureau investigated the killings, but it's also a much broader history, exploring the history of the Osage and how the effects of these murders still linger today. Scorsese has said before that his initial drafts of the film focused primarily on the FBI, but the script went through major changes — particularly by shifting the film's perspective to Mollie and Ernest Burkhart.

Here, Grann opens up about the changes Scorsese made from his book and what he hopes audiences take away from this not-so-distant history.

Melinda Sue Gordon/Apple Lily Gladstone, Robert De Niro, and Leonardo DiCaprio in 'Killers of the Flower Moon'

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: You spent years researching the book, and the film took several more years to get to the screen. What's it been like to watch the reaction to the film now that it's out?

DAVID GRANN: For me, the main reason I embarked on the project originally was to address my own ignorance and the fact that so many others outside the Osage Nation were unfamiliar with this history. The most rewarding part of watching and following this journey is to see this history radiating out into the world, to see people beginning to have conversations about it and filling in what too many Americans had really excised from their consciousness and their conscience.

I spent about half a decade working on the book with members of the Osage Nation, recording stories from the Osage elders. What has been really important and gratifying to see was the level of involvement of the Osage Nation in shaping the movie. They've been involved at every level, from the production to the costume designs to making sure that the Osage language was spoken to the Osage actors who have speaking roles. That's been remarkable to see.

I spoke to some of the Osage consultants who worked on the film, and they all talked about how important it was to them to actually film on Osage land with Osage involvement.

It's what gives the film its power, I think, and its authenticity. I remember when I visited the set, I encountered many members of the Osage Nation, many of whom had become friends of mine over the years. They were acting in the film and playing key roles. Some of them were central to my book and research, and many of them are descendants of people who were killed during the Osage reign of terror.

One of the scenes I watched that was so powerful is the scene with the Osage tribal council. There's an incredible oration by Yancy Redcorn and Everett Waller, and I've been told that a good deal of what ended up in that scene was them improvising, taking from their own lives and the oral histories that were passed down to them. I've been told that when Scorsese heard them, he said, "Oh, let's make sure we put that in the film." It gives the film its kind of bracing power.

You spent many years researching someone like Mollie Burkhart, piecing together her life through interviews and historical documents. What's it like to see Lily Gladstone bring her to life on screen?

It's an unusual process because when you're a historian, the people you get to know are two-dimensional. You get to know them through documents or photographs. You get to know them through snippets of testimony and letters and transcripts that you might uncover, but they're not three-dimensional or fully inhabited. There's always a kind of surrealness when you see these people — especially Mollie — suddenly brought to life. Suddenly, her conscious is being inhabited.

For me, Mollie Burkhart was always the heart and soul of the book. The whole first third of the book is from her perspective, and then the last third is told largely from the descendants' point of view, reconstructing what had happened to her and her family. I can't think of anyone who could have played her better than Lily Gladstone. Mollie had this quiet force about her. She was somebody who was born in this lodge, speaking Osage and practicing the Osage traditions. As a young girl, she was forcibly uprooted from her home and made to go to one of these boarding schools, where she was no longer allowed to speak the Osage language. She had to capture what they referred to as "the white man's tongue." She could no longer wear her blanket. And then within just a couple of decades, she's living in a large house because of the oil money. She has married her chauffeur, Ernest Burkhart, this white settler. So, she's somebody who straddles not only two centuries but two civilizations.

One of the things that always struck me about her was that as her family is being systematically targeted, she begins to crusade for justice. She is banging on the doors of the authorities, trying to offer evidence and testimony. She is hiring private detectives, she's putting out rewards, and while she's doing all of this, she is putting a bullseye on her back, which she knows. It took this remarkable force and courage, and I thought Lily captures that so well and so brilliantly. I mean, I'm not a cinephile, but she kind of reminds me of a silent actress in a way. It was the first time I could really understand the power of what a silent actress does. She does so much just in her expressions.

Apple TV+ Lily Gladstone in 'Killers of the Flower Moon'

For you as a historian and as a reporter, how did you go about understanding Ernest and Mollie's marriage? It's one thing to follow the facts — when they were married, how many children they had — but how did you try to understand the actual feelings they had for one another? It seems from your book and the film that there was real love there, but also tremendous cruelty and betrayal.

Obviously, when you look back in time and these people are no longer living, it is one of the things you're trying to understand: What was this relationship between them? There were several documents and little bits of testimony that gave a sense that there had been this genuine affection between them, and Ernest did share some affection for her. You can see that in the letters. I found a letter from Mollie to Ernest where you get a sense of that. I think she refers to him as "my dear husband."

I asked many Osage this question, including the descendants of the family and others. It's unfathomable for her to have thought that somebody would be marrying into her family while plotting to kill her and possibly even her children. At least in the early parts, she shares genuine affection for Ernest, not realizing exactly who he is.

The other thing that was so critical for me in trying to understand Mollie was interviewing the descendants. One of the people I tracked down was Margie Burkhart, who's the granddaughter of Mollie. She was so helpful to me on so many levels. She shared with me oral histories. She also shared what she had heard, which is that there was affection between them. That affection was then betrayed in the most horrifying way. In talking to Margie, one of the things she did was underscore for me how this is still living history. We're not talking about colonial times. When I was doing research, it was less than a century ago. Even today, it's just a century ago.

I remember she shared a photograph with me. It was a photograph of her father, who was Mollie's son Cowboy, and Mollie's daughter Elizabeth. It showed them as two little kids, maybe 6 or 7. They're holding the hands of a man. As you follow your eyes up the photograph, the photo is ripped off at the neck of the man. I obviously suspected what it was, but I asked her, "What happened?" She said, "Well, my father ripped it off." It showed his father, Ernest Burkhart, whom he referred to as "dynamite."

That's what's so powerful about this story. Like you said, it's not colonial times. This was just a generation ago.

It really does still reverberate to this day. I don't know if this is a digression, but to me, one of the most important parts of this history and what I hope people will understand is that when I originally began researching this book, I thought of it as this kind of singular evil figure who committed these crimes. It was William K. Hale who committed them, with his nephew Ernest and another henchman. I believed that because that was the theory the FBI had put forward, and that was the widely accepted version of the history.

But the more research I did into this and as I spoke to many of the Osage elders, they would share with me history and records about other killings in their family, other suspicious deaths that were never properly investigated by the FBI and that were not connected to William Hale. And I found other records that really revealed that this had been a systematic murder campaign.

So, after spending about a year and a half on this book project, my original conception of the book was completely destroyed. I realized that this was much less a story about who did it than who didn't do it. It was really about this culture of killing and complicity. I think the film shows that, and you get glimpses of that. This was really about the many people who were carrying out these crimes. There were doctors who would be administering poison, and there's evidence of morticians who would ignore a bullet wound. There were all these guardians and businessmen and lawmen who were in on it or on the take. And there were many others who were complicit in their silence — all because they were getting wealthy from what they referred to as the, quote, "Indian business."

I hope that people who watch the movie and dig into the history further will reckon with that part of that story. It's much easier if we think of this history as one bad apple, and if you just remove that figure, it's easier to process. But what I think we need to process is that these crimes were really systematic and societal.

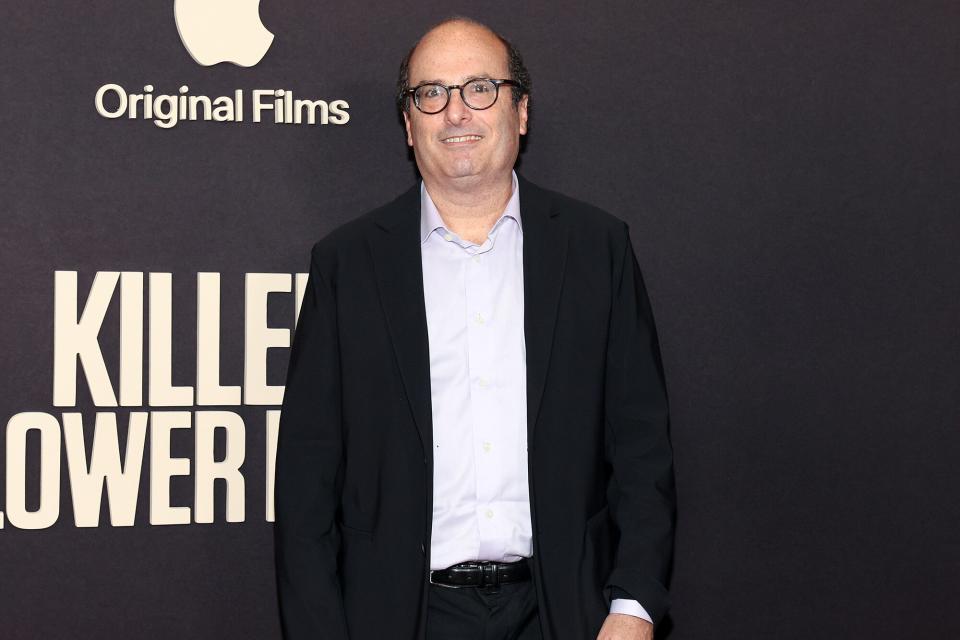

Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images David Grann at the New York premiere of 'Killers of the Flower Moon'

Martin Scorsese has talked quite a lot about how his initial film script focused more on that FBI investigation and had a more narrow scope, until he reframed the story to focus more on Mollie and Ernest. How did you feel about that shift in focus?

So, the book was really told in three points of view. The first point of view was Mollie's; the second point of view was the FBI's; and the third point of view was from the present and from the descendants, showing that although the FBI caught a couple of killers, they really had failed to expose the much deeper conspiracy. It was a kind of a triptych of a book and a very sweeping history. It goes all the way back to when the Osage laid claim to the central part of the country and all the way up to the present. In a film, I don't think that's possible. You can't, nor should you. So, I think their decision to focus on that relationship was the right decision.

I remember when they first called me [about changing the focus], I said, "Oh yeah, I would definitely do that." I never saw the first script, so I don't really know exactly what it contained. But if you just focus on the second part, it would have been a misrepresentation of the history; it would have only been a slice. I think focusing on this relationship was the right decision because that relationship is also very representational of the crimes that took place. If you can kind of understand that relationship a little bit, you can begin to understand what happened on a macro level. So, I thought that was the right way to go about it.

Your writing has been adapted into films several times below. I'm curious: What, if anything, felt different about this film?

I feel really lucky and blessed because as a writer, you don't have that much control over these projects. And I don't try to because I never aspired to write movies or be in the film business. I really love what I do, and I focus on that. For me, the trick is always getting it into the hands of people who really know what they're doing. In that regard, I feel really blessed to have had a chance to work with James Gray, Ed Zwick, and so many of these other really talented filmmakers and actors.

I will say that none of those projects were of this scale and magnitude. I'll also say that this film deals with a history that is so sobering and really one of the worst racial injustices in American history. So, based on the subject matter and the scale, in that sense, it was different. And therefore, the development of the project was different.

Any writer who says they're not nervous when a book is going to be adapted is lying. You're nervous about what could happen, especially with a subject matter like this. But the second that Scorsese and his team came on board, and the second they began working with the Osage Nation and they decided to shoot on location, I knew they were going to do something lasting and something that would be authentic. For me, the thing that makes this film so good is that it's its own thing. It's a complement to the book, but we're both moving towards the same deeper truths, through our own distinct mediums.

I know Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio have also acquired the film rights to another one of your books, The Wager. How do you feel about them teaming up again to tackle that story?

I got a front-row seat to watching them develop Killers of the Flower Moon. I can't underscore enough how they showed such a level of care to the history and a real commitment to the story. So when they expressed interest in The Wager, it was the easiest decision I've ever made. [Laughs] I don't think the project could be in better hands.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content:

How Osage influence brought Killers of the Flower Moon to life

Martin Scorsese rewrote Killers of the Flower Moon so it wasn't just 'about all the white guys'

Osage consultants weigh in on the complex feelings of watching Killers of the Flower Moon

Killers of the Flower Moon is a brilliant synthesis of Martin Scorsese's filmography