What Killed the Memphis Country Blues Festival? New Doc Exhumes a Forgotten Fest

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nearly everyone has heard about Woodstock and the US Festival, but the same can’t be said for the Memphis Country Blues Festival. Depending on the year, the annual gathering held in Memphis between 1966 and 1970, was the place to see and hear genre icons. Country-blues guitarists Furry Lewis and Mississippi Fred McDowell, along with blues and R&B character Rufus Thomas, all played there, as did folk and rock guitar heroes Johnny Winter and John Fahey. The Rolling Stones were even invited to appear (more on that later), and some festival footage was included in a public television special in 1969.

But more than 50 years after the Memphis Blues Festival, as it was known in its early years, ended its brief run, the very history of the event has all but vanished. Few recall its impressive lineups nor the way it brought together white and Black audiences to see largely Black musicians, and at a time of racial segregation in the South.

More from Rolling Stone

The Rolling Stones Release Teaser for 'Sweet Sounds of Heaven' with Lady Gaga and Stevie Wonder

Olivia Rodrigo, Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, and All the Songs You Need to Know This Week

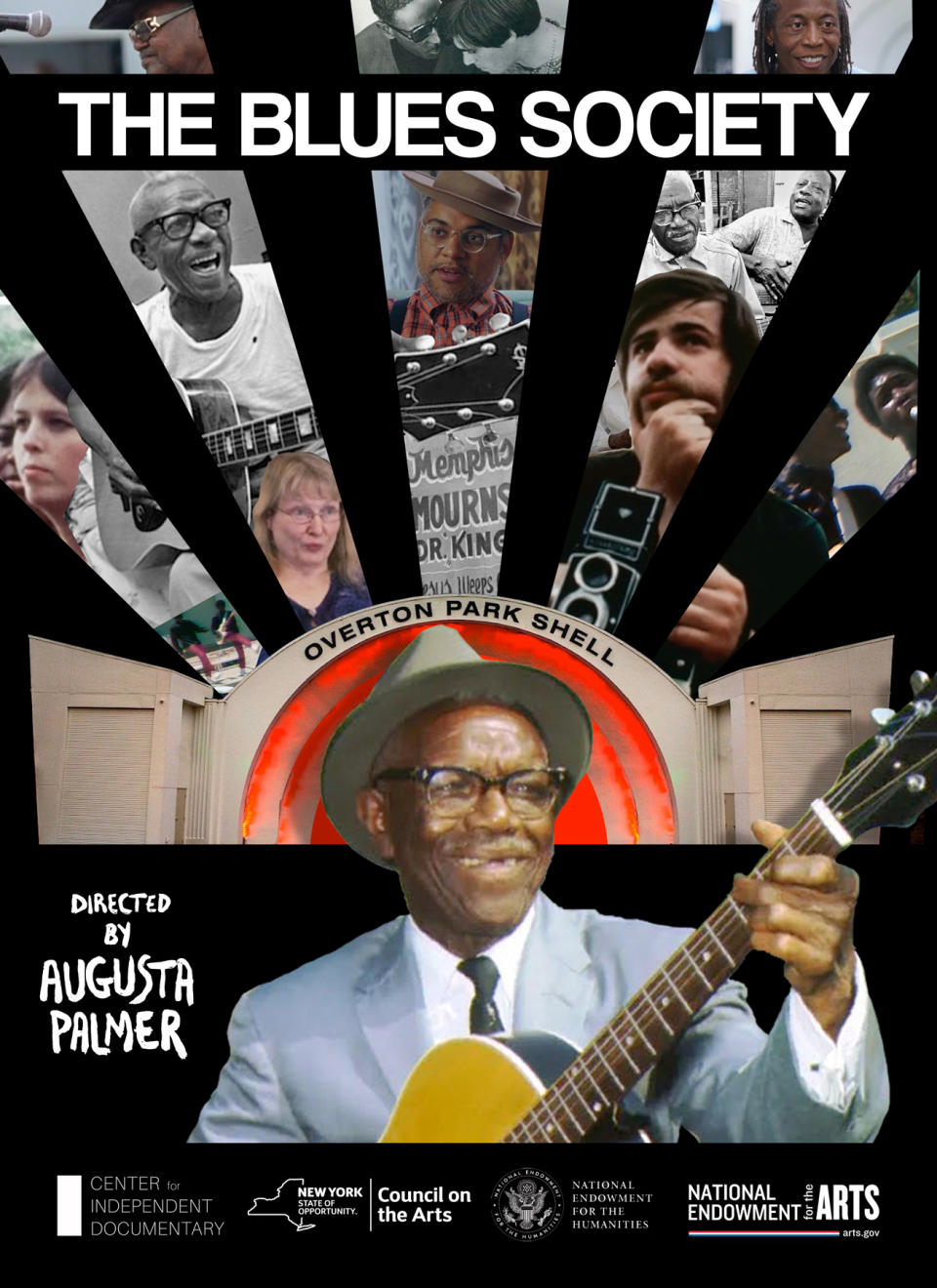

Now two documentaries are helping the long-forgotten concert series get its due. Staring with Memphis ’69, a 2021 film focusing on that year of the festival, and continuing with director Augusta Palmer’s new The Blues Society, the fest’s history is being exhumed while also raising new questions about why it disappeared and the complex relationship between the white organizers and the Black musicians they were ostensibly helping. “My film tries to think about how can we look at this now,” Palmer says. “The organizers were brave and doing something exciting, but they also had a type of white privilege that the artists they were supporting didn’t have.”

The Blues Society, which premieres at the Indie Memphis film festival October 29th, marks the first documentary on the entire lifespan of the festival, held at a bandshell in Memphis. (Right before the first of the festivals, in 1966, the Ku Klux Klan had a rally in the same spot.) Palmer has a deep connection to the topic. Her father, the late Robert Palmer, was one of the organizers, as well as a music critic and blues historian (for Rolling Stone and later The New York Times). “The festival was really formative for my dad, but I didn’t know him growing up,” says Palmer, who was raised by her mother Mary Branton and didn’t meet her father until she was 12. “I only found fairly late in the process an article my dad wrote for Changes magazine about the 1969 festival. I learned how much he was involved that I didn’t know.”

Palmer, a filmmaker and associate professor in the Department of Media and Communications at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, started on the project in 2016, and it’s easy to see why it’s taken this long. The 1969 festival was filmed for a TV special by filmmaker Gene Rosenthal. But in a telling sign of how little anyone thought of the Memphis Blues Festival at the time, no film footage exists of the 1966, 1967, 1968, and 1970 events, only some still photos.

But between rare and never-before-seen 1969 footage and new interviews with some of the organizers and participants, Palmar was able to piece together the saga. In that regard, The Blues Society recalls Questlove’s award-winning doc Summer of Soul, about a forgotten 1969 New York soul festival. “It’s a similar story in terms of unseen footage that was locked in a basement,” Palmer says. “It wasn’t accessible to people for a long time.”

Palmer also sough to tell the story for different viewpoints. She recruited leading Black writers and historians like Memphis writer and filmmaker Jamey Hatley and sociologist Zandria Robinson as well as women involved in the festival. Those included Nancy Jeffries, the future A&R executive who, along with Robert Palmer, was in experimental rock-jazz band Insect Trust. Jeffries pitched in on various aspects of the festival: In the film, she recalls giving a ride to Bukka White and being pulled over by the police, who were suspicious of a white woman driving a Black man.

“The organizers, like my dad and Nancy, saw that the rock world, the Rolling Stones and all the rest, were making money based on the blues,” Palmer says. “But these guys who’d been around and originated that style, who’d had serious recording careers in the Thirties and into the Forties, were not profiting from that, either through money or gigs. So this was a benefit for these blues heroes of theirs.”

What Palmer calls the “subtle” white privilege of the time is depicted the treatment of Nathan Beauregard, an elderly Black blues guitarist and singer then billed as the oldest living blues singer; at the time, he was said to have been at least 100. But as Palmer and her researchers learned, Beauregard was likely only in his seventies. “People adored Nathan, but it seems clear that that situation was a projection of the ‘magical Negro,’ the way academics talk about it,” she says. “They’re not thinking about what life was like for a real human being. There wasn’t a way for Nathan to really tell them who he really was. The main selling point was, ‘Here’s this ancient guy.’“ The film’s depiction of Lewis is especially poignant. Injured on the job and sporting a wooden leg, Lewis was known more for his job as a street sweeper than a musician.

The Blues Society also reveals the way the festival expanded its musical offerings with mixed results. The Bar-Kays — a revamped lineup of the funky backup band that lost some of its original members in the same plane crash that killed Otis Redding — were added in 1969, as was Johnny Winter. As reverent as Winter was of the blues, his appearance seemingly led to more than 2,000 fans climbing over the fence and not paying admission. In the film, Branton is heard announcing that those gatecrashers were now a problem and that everyone should pass a hat around to raise money for the musicians to compensate for lost ticket sales.

The festival also missed an opportunity to reach an even wider audience. As Rolling Stone reported at the time, the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet listed Mick Jagger and Keith Richards as the writers of “Prodigal Son,” rather than its actual composer, bluesman Reverend Robert Wilkins. The mistake was corrected, and according to the film, Jagger called Wilkins, who suggested they meet in person rather than talk by phone. The band was invited to play the festival, but when they asked for the city to pay for their hotel and airfare, the deal was off. “As much as it pains me to be sympathetic with the city, it could have been something that neither the city nor the festival were prepared in terms of providing security,” says Palmer. “On the other had, it could have been really amazing. It would have opened up the importance of Memphis blues to a more mainstream audience.”

For reasons that remain unclear, the Memphis Country Blues Festival petered out by 1971. Palmer thinks the organizers, including her father, were busy with other projects, like Insect Trust. The city’s sudden involvement in the festival, and the way it attempted to bring in “their own artists,” according to Palmer, and incorporate the concert into other municipal events, likely added extra bureaucracy and headaches. As the film points out, some Black music fans at the time also considered blues “old hat” and were far more interested in funk and soul.

The arrival of The Blues Society comes as a propitious time, as a new generation of young, Black blues musicians, like Buffalo Nichols and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, seek to reclaim the music from the white musicians who’ve come to dominate the genre. “It’s worth telling this story because it’s this moment when you have hippies and Black blues players come together and start to communicate and work together,” says Palmer. “Music is a very powerful force. But white people loving the blues didn’t end racism. And in some ways it perpetuated racism, because white people became the managers of Black blues artists, some of them acting fairly, and a lot of them not It’s a complicated story, and it’s worth looking back at that moment and seeing it warts and all, and not just as a triumph.”

Best of Rolling Stone