Kevin Rowland: ‘I thought, if anyone tries it on with my woman – I’m going to hit him’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kevin Rowland has an excellent memory. The Dexys frontman says he can recall his life in vivid detail. “It’s ridiculously good,” he says. “I can remember what people were wearing, describe a room. Mad stuff like that.”

So he is sceptical about Searching for Dexys Midnight Runners, a book published on June 6, in which dozens of current and former members of the band he founded more than 45 years ago talk about their time in one of the best-selling British acts of the 1980s.

Dexys (Rowland shortened the name in 2011) has always had a revolving-door policy to its lineup. Some members – trombonist Jim Paterson, guitarist Kevin Archer, violinist Helen O’Hara among them – he says were core to the band; others were hired hands. Not everyone shares his powers of recall, and not everyone was as invested as he was.

Rowland did not cooperate with the book. “I’m not interested,” he says. What seems to concern him most is Dexys being packaged for the nostalgia market. “It wouldn’t be enough for me to just look back and say, ‘Oh, it was great back then’. That would be death to me. It’s about what I’m doing now.”

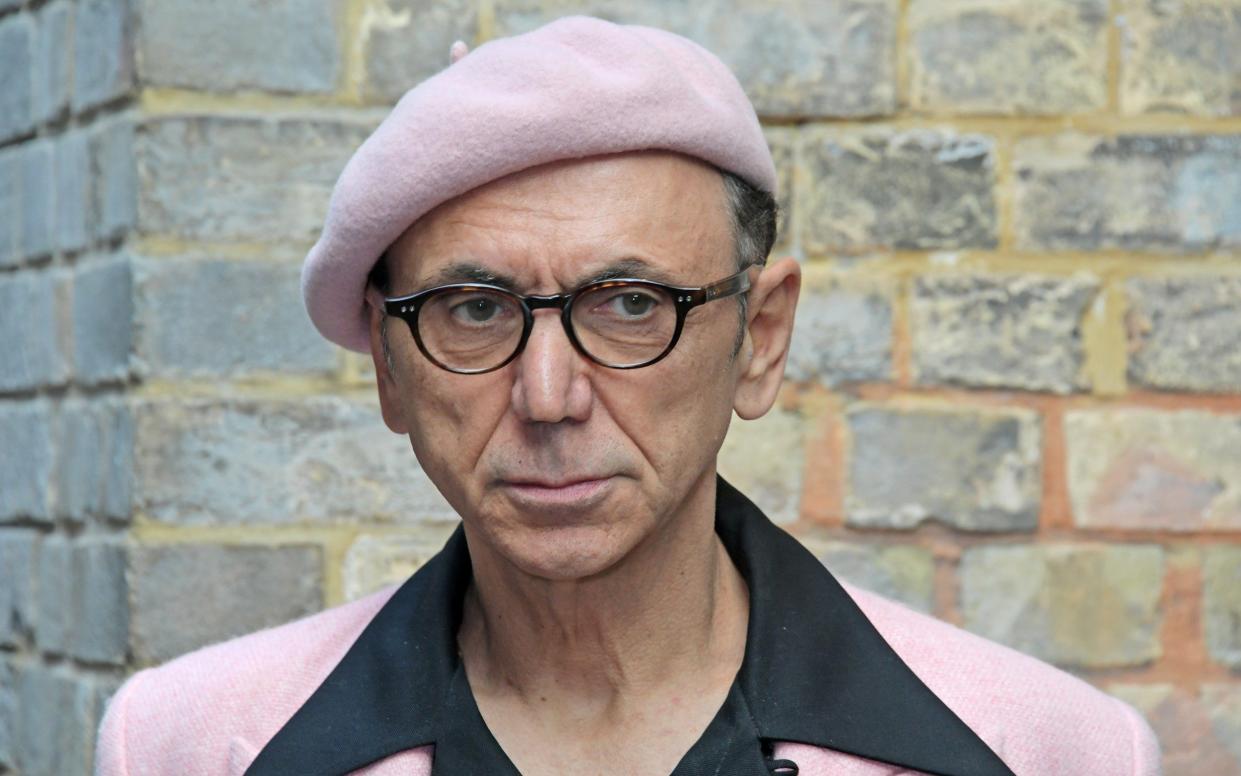

At 70, the irrepressible Rowland is more productive than ever. We are in his local pub, a smart Hackney hangout, to talk about Dexys’ next release – a live version of 2023’s critically acclaimed album The Feminine Divine – and the band’s forthcoming nine-date UK and Ireland tour of the same album, which includes a coveted evening slot on Glastonbury’s Park Stage on Friday night.

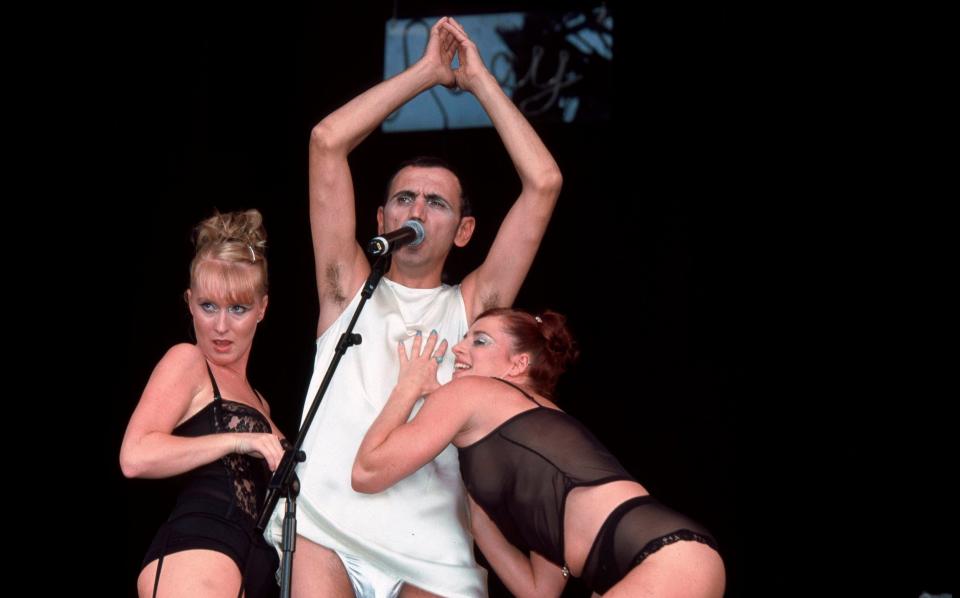

The Feminine Divine is a concept album, a confessional Rowland biography of sorts, in nine songs. It tells the story of his 30-year progress from a sexist male who saw women as possessions to be protected (a mindset he attributes in part to his upbringing) to an enlightened champion of women.

The first track, The One That Loves You, he wrote in the early 1990s. “It’s basically saying, if anyone tries it on with my woman, I’m going to hit him,” he says. “That’s exactly how I thought and felt.”

The rest of the songs are new, soulful compositions celebrating Rowland’s abandonment of his ego in a female-led relationship.

I wonder if the MeToo movement changed him, but he says there was no epiphany. He started to shed his machismo after 1993, when he went into a recovery programme from cocaine addiction, after years lost to the drug following the commercial failure of Dexys’ third album.

His therapy revealed all sorts of ingrained unhappiness. “My dad was a tough guy. He wasn’t going around fighting everybody, but I’d somehow picked up that that was what I needed to do. Otherwise I was going to get trod upon. I realised it had been a big mask, that macho thing I grew up with.”

I’m struck by the contrasting joyfulness of I’m Going to Get Free, the album’s third track, and a recent single – a maddeningly catchy song in which Rowland and his backing singers act out a kind of therapy session.

Were you frightened?

I was

Of your violence?

Oh, yeah. I had so much hate in me

I stopped and I looked and I said to myself, I’m not liking what I see

And now I’m going to get free

It sounds like redemption. “I thought it was a strong statement. I meant every word,” he says.

Rowland was born to an Irish Catholic family in Wolverhampton in 1953 and spent his childhood moving around, first to Ireland, back to Wolverhampton then to north London.

“It was a working-class background. If your dad’s a builder and you’re of Irish descent, absolutely. I never really met middle-class people until I came into the music business.”

As a young man, he loved Philadelphia soul, and was gripped by Roxy Music. Bryan Ferry was the biggest influence on his vocal style. “When I first heard him, I thought what the f–k is that? It was brilliant.”

Rowland’s tough background gave him phenomenal drive and productivity. He had a clear vision for Dexys Midnight Runners in the late 70s and early 80s, which led to early commercial success. The band’s second single, 1980’s Geno, went to number one.

He concedes he was a taskmaster, insisting on full-time rehearsals, mandatory uniforms of woolly hats and donkey jackets, even an exercise programme involving running as a group to bring out a collective fighting spirit.

Could he have had a career in pop music if he were starting out today? “I don’t think so, no. One big factor was the dole, unemployment benefit you could live on. I’m not sure you can now, I don’t know if you can survive. But you could then. We did that for two years and we rehearsed and we saw it as our student grant.”

The 1980 album Searching for the Young Soul Rebels was followed by the platinum-selling Too-Rye-Ay with its monster global hit Come on Eileen.

In the early 1980s the UK was convulsed by the Troubles. The cover of Young Soul Rebels featured a newspaper photograph of a boy fleeing his Belfast home, clutching his possessions as civil unrest breaks out around him.

Shortly after Come on Eileen was released in the summer of 1982, the IRA killed 11 people with bombings of military parades in Hyde Park and Regent’s Park. Rowland describes how, when the track was played for the first time on a Birmingham radio station, a presenter apologised for its Irish-inflections “just because it was Irish-sounding”.

The lyrics were far from political. But Rowland says he felt a duty to bring Irish inflections into music in a febrile time. “It felt subversive. You weren’t supposed to say anything about Ireland in the 1980s. Nobody wanted to hear it. Even people on the Left didn’t talk about it, and I felt Irish culture was misunderstood.”

Then came long periods of disappointment. Dexys’ 1985 album Don’t Stand Me Down failed to sell. “It was heartbreaking, we couldn’t have done anything better than that album,” he says. “We took too long, three years and the whole landscape had changed. Live Aid had happened, we didn’t get asked. Everything seemed bigger, more corporate.”

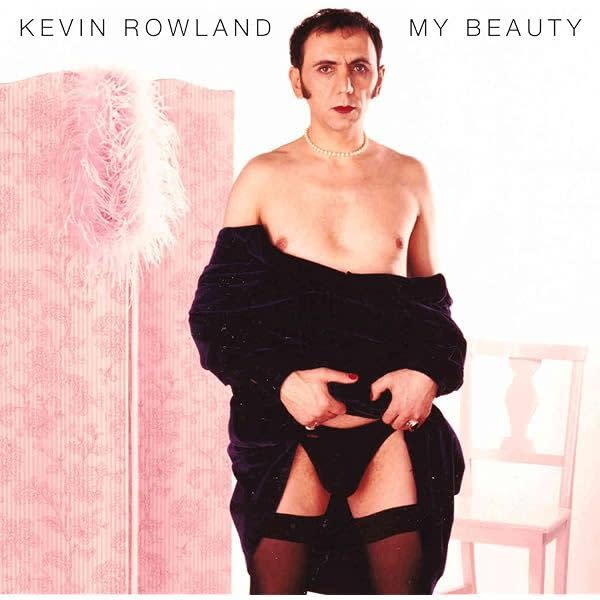

Rowland hurtled into cocaine use, lost much of his fortune and began recovery. Then 1999’s My Beauty, his comeback solo album of covers in which he reinterpreted lyrics to reflect his own experiences and appeared on the cover wearing a dress and stockings, was met with bafflement and derision. He was accused of having a nervous breakdown. Even the Guardian ran a Rowland interview with the headline “Frocky Horror”.

“And that’s the Guardian! Unbelievable.” I suggest he was 20 years too early for the era of gender fluidity. He agrees. “I was doing what felt intuitively the right thing to do for me. The worst thing was everyone thought it was fine to say those things.”

When Rowland saunters to the bar to order another mineral water, the pub’s punters nudge one another in whispered recognition of one of British music’s most distinctive frontmen. His star quality comes from an almost supernatural calmness and an elevated sense of style.

Rowland is wearing an outsized baker’s cap, an apple-green jumper, white baggies, plimsolls and a long, herringbone coat with a plush fur collar. He could be a particularly well put-together gangster – he tells me he designs his clothes himself with the help of a seamstress in Dalston.

Rowland might not endorse the forthcoming book. But I point out its publication suggests a loyal fanbase. He agrees. In fact, he is drawing on his excellent memory to write his own story – a project he started 20 years ago. “I’m just finishing it,” he says. “I don’t know what the word memoir means, but I’ve written about my life.” He hopes to publish the book imminently, though he says he keeps tweaking it.

As we leave the pub, he spies my preview copy of Searching for Dexys Midnight Runners.

“Now I’m curious about that book,” he says. “It seems kind of an anoraky idea to me, but there you go… I might even read it, just for the hell of it.”

The Feminine Divine Live is released on May 24. Dexys tour begins on May 24; tickets: dexysofficial.com. Searching for Dexys Midnight Runners by Nige Tassell is published by Nine Eight Books on June 6