Kenneth Branagh Returns to ‘Belfast’: How His Autobiographical Film Became an Oscars Frontrunner

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In March 2020, Kenneth Branagh retreated to his home just outside London. And, like much of the world, he stayed home as COVID cut a deadly path around the globe, upending life and closing the cinemas and West End theaters where Branagh has made a name for himself as an actor and a director over the past four decades.

He holed up in his office and began jotting down notes for what would become “Belfast,” the most personal of the 19 features he has directed over the course of his career, and a movie that has vaulted itself into the front of this year’s Oscar race. It is a coming-of-age story about a 9-year-old boy named Buddy, growing up in Northern Ireland in the shadow of political and sectarian violence — which somehow defies this grim setting to be moving, humorous and deeply human. Though framed in the 1960s, it is a fitting film for our times, with a bigheartedness that is the antidote to all the division and antipathy taking place in a plague-stricken world.

More from Variety

'Belfast' and 'C'mon C'mon' Highlight SCAD Savannah Film Festival as 'Magic of Big Screen' Returns

Oscars Predictions: Best Picture - 'Belfast' Continues to Rack Up Audience Awards

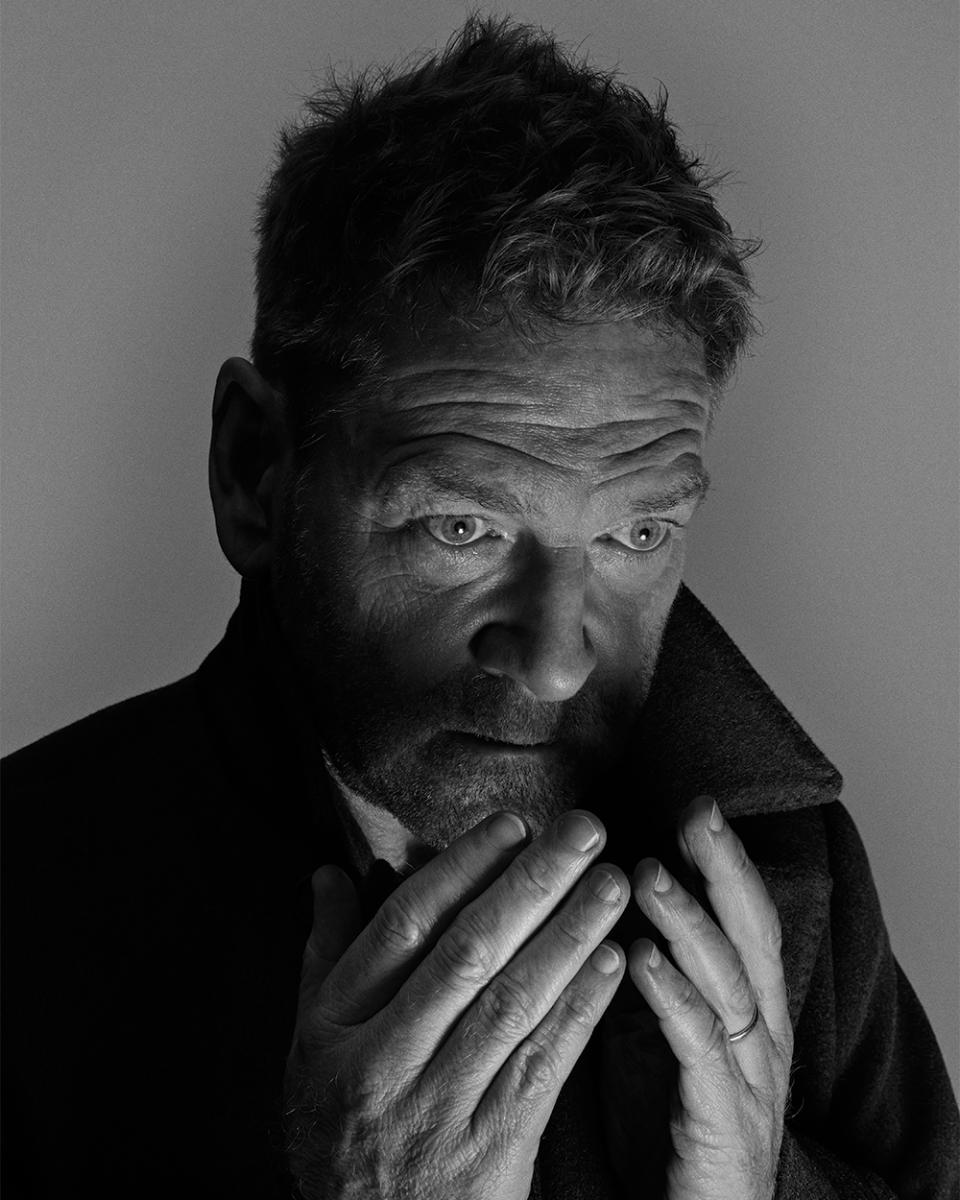

Nadav Kander for Variety

“It felt as though the gestation period was about 50 years,” says Branagh, 60. “There are some things that need to come out and when they do come out, they tumble out swiftly. I was not distracted by other projects or anything else. For some people the lockdown was an aching void, but for me I was lucky enough to fall into a creative drive that was all-consuming.”

The words poured out of Branagh, taking him roughly eight weeks to assemble into a shooting script. Maybe it was something about the odd kind of limbo that accompanied lockdown, the sense that time had been suspended, while public health requirements left all of us cut off from friends, family and the other totems of modern life, but Branagh found he was able to reach back a half century and easily clear away the mists of memory. For as long as he could remember, he wanted to make a film about his family’s decision to move from Belfast at the height of “the Troubles,” but it remained an unrealized ambition. During COVID, Branagh discovered that he could more easily access the thoughts and feelings that had informed his boyhood and find parallels between the pandemic and the social disruptions that led to his own loss of innocence.

“A rupture happened for me in the summer of 1969,” says Branagh, reflecting on the project in a 90-minute Zoom interview conducted from his living room. “There was a moment in life where things were settled and happy, and then immediately and instantly they were unhappy and unsettled.”

In the finished film, which Focus Features debuts in cinemas on Nov. 12, that moment is crystallized in a scene where Buddy (played by 11-year-old newcomer Jude Hill) is called in for tea, forcing him to interrupt fighting imaginary dragons on a drab city street for his afternoon snack. As he races down the block, he finds himself face-to-face with a massive, unruly crowd. Soon Buddy’s life will be unsettled, and the alleys and thoroughfares where he once roamed, carefree, interacting with neighbors who knew his name and looked out for him, will be bisected by barricades and marred by military checkpoints. His block, a mixed neighborhood of Catholics and Protestants, becomes a tinderbox as the communities turn against each other.

“The atmosphere of the streets themselves was a very electric one,” says Branagh. “There was singing and music, and it was one where laughter or entertainment could burst forth at any moment, but so could violence. The possibility of violence hung in the air.”

Re-creating that moment in history was a technical as well as an artistic challenge. Initially, Branagh had hoped to shoot the film in the same streets that had served as a sort of cobblestone playground, but when he scouted Belfast, he found that too many of the familiar buildings had been torn down. Plus, when production was set to commence in September 2020, vaccines had yet to be made available and Hollywood was only slowly figuring out ways to shoot amid a highly transmissible, potentially fatal virus. So Branagh and his team built parts of the city in the parking lot of an exhibition center in Farnborough, roughly an hour outside London, to reflect what Belfast would have looked like in that turbulent era.

They also introduced rigid safety protocols. Cast members and production staff were kept in pods, social distancing was enforced, mask wearing was required between takes, and the whole company was essentially asked to quarantine when not on set for the duration of the seven-week shoot. And yet, despite the stringent rules, the ensemble, which includes Jamie Dornan and Caitriona Balfe as Buddy’s working-class parents and Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds as his doting grandparents, say that filming was a joyous occasion.

Nadav Kander for Variety

“It was the most fun of all the jobs I’ve ever done, and that stems from Ken,” says Dornan. “He created a very relaxed atmosphere. It’s paradoxical, because there was a pandemic happening, but there was a lot of laughter. There was just a sense of we’re running on fumes — let’s make the most of it.”

Dench, who has appeared in numerous films that Branagh has directed in addition to working with him consistently onstage, says part of the key to his success is his abiding belief in preparation. He arrives on set with a firm sense of what he wants to do, but also has a politician’s ability to coax a performance out of his cast.

“He’s just planned it all so well,” says Dench. “You never feel secure, not in this business, but you feel as secure as you can with Ken. Not only does he know what he wants, but he puts it in a way that makes you think you’ve chosen the right way to do it, and that’s a wonderful virtue to have.”

At the center of the film is Hill, a wide-eyed, preadolescent force of nature who holds the screen despite never having appeared in a movie. The young actor is a competitive dancer, something that made him accustomed to needing to be up early and on time for events. He was also used to having to wait around for hours while judges made their deliberations, giving him an ingrained patience that came in handy on film sets, where it can take hours for crews to set up between scenes. Other aspects of moviemaking took some adjusting.

“He was a rough diamond,” says Branagh. “On the first two days, my single direction was ‘Jude, stop looking at the camera. Jude, don’t look at the camera. Jude, what mustn’t you do? Look at the camera.’ But he polished up quickly and the scales fell from his eyes, and he delivered a marvelous performance.”

When Branagh’s parents were considering uprooting their family to flee the violence and resettle in the U.K., where his father, a plumber and joiner, had a job offer, their 9-year-old son was adamant that his future was there in Belfast. He wanted desperately to stay behind in the city he knew so well. Over the decades, Branagh says he’s come to better understand the courage it took for his parents to make that break and the impact it had on all their lives.

“I was a very happy kid. I was very playful and imaginative. And after we moved, I became a much more withdrawn individual,” says Branagh. “As a family we became a much more withdrawn group. We were less sociable and more guarded.”

Branagh’s collaborators feel that the decades that the writer and director spent teasing out the story allowed him to approach the material with more nuance.

“As we get older, we are able to see our parents in a new light,” says Balfe. “That’s what Ken did with this film. He treats his parents and grandparents with such empathy. He understands their struggles.”

• • •

What makes “Belfast” notable is that, like John Boorman’s “Hope and Glory” or Louis Malle’s “Au revoir les enfants,” it applies a child’s perspective on war and trauma. That lends the film a certain sweetness — Buddy may be living in the shadow of violence and ever-encroaching unrest, but he still loves his comics and his TV Westerns and the trips to the local cinema. Branagh and his longtime cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos, with whom he has worked on seven other films, opted to shoot the movie in black and white. That was intended as an homage to Henri Cartier-Bresson, the famous street photographer who had an uncanny ability to capture candid, unguarded moments. They also framed many shots from the ground up, an attempt to replicate the way that Buddy sees his surroundings and the towering adults who are making important decisions all around him.

“We shot so many things through the bars of a banister or through windows or barbed wire to give this experiential sense,” says Branagh. “I’d had all this freedom of movement, and that all changed. Suddenly life became a more furtive exercise where you had to listen to grown-ups talking about futures that you had not previously been aware of. They were withholding information from you, and you suddenly became a kind of voyeur starting to hear things that in your imperfect 9-year-old way you’re trying to make sense of.”

Nadav Kander for Variety

The film also reveals some of the artistic influences that helped shape Branagh. Buddy’s family visits the local movie palace, watching films like “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” and “One Million Years B.C.,” as well as takes a trip to a theater for a performance of “A Christmas Carol.” Those on-screen and on-stage moments are presented in color, a symbol of the bold new world being opened for Buddy and, by extension, Branagh. There’s also an Easter egg of sorts, with Buddy at one point glimpsed reading a Thor comic book, a sly nod to Branagh’s future role directing the first film adaptation of the Marvel comic.

“Those original Jack Kirby illustrations for Thor were eye-popping,” says Branagh. “I did think about shooting young Jude, sitting on the pavement reading it while the comic book color leaps out, but we decided it was too much.”

The illustrations of the action on Asgard that so transfix Buddy, it was decided, would remain in stark black and white. Another stylistic decision that unites the different strands of “Belfast” is Branagh’s heavy use of Van Morrison songs. The music of the crooner, a native of Belfast, doesn’t just appear in the form of eight pop standards such as “Brown Eyed Girl” and “Days Like This”; he also penned incidental music and an original song for the movie, “Down to Joy.”

“He responded to the film,” says Branagh. “He has that delicate relationship with his hometown that happens with many Irish people who spend much of their life traveling. You have a tenderized, somewhat melancholic relationship to the place that you left, and that’s articulated in the film.”

As infectious and stirring as many of those songs remain, it may be hard for some audience members to separate the music from its increasingly controversial author. Morrison has been an outspoken critic of COVID health mandates, and his most recent album, “Latest Record Project, Vol. 1,” contains lyrics that some have interpreted as anti-vaccine and anti-science.

“He’s a man of an independent mind,” says Branagh. “What I understood through talking with him is that the passion that he felt wasn’t so much an anti-vaccination stance, but a passionate desire and a hope to have live music return. We didn’t connect on that level. He’s his own man, but as an artistic collaborator he was a tremendous ally.”

Perhaps it’s the unforgettable soundtrack or the evocative cinematography or the richly inhabited performances, but “Belfast” has emerged from the fall festival season as the Oscar front-runner, with many pundits predicting that Branagh could land nominations for best picture, his screenplay and direction, with Dench, Hinds, Dornan and Balfe seen as supporting actor contenders. Not only did “Belfast” score with critics in the Toronto and Telluride festivals, but it also snagged TIFF’s prestigious People’s Choice Award, which is a reliable awards season bellwether — previous recipients include best picture winners such as “Nomadland,” “The King’s Speech” and “Green Book.”

But for “Belfast,” it is unclear whether buzz on the film can translate into ticket sales, and that’s a bigger question at a time when COVID and its variants have depressed the box office and made moviegoers, particularly older audiences who will swoon for Branagh’s picture, skittish about returning to cinemas. Focus will release “Belfast” right before the Thanksgiving holiday in several hundred theaters around the country. That’s a fairly large footprint for an indie film, but the hope is that word-of-mouth will be enough to enable the film to compete with higher-budgeted releases such as Marvel’s “Eternals” and the Will Smith drama “King Richard.”

“People respond to this film on a human level, and I think the movie is going to become a conversation point,” says Focus Features chairman Peter Kujawski. “I’ve seen it with audiences, and it works. If people see it and talk about it, it will play for a long time.”

Hinds, who could snag his first Oscar nomination for his work as Buddy’s mischievous grandfather, believes that because Branagh made such a specific story, one steeped in the particulars of his childhood, the saga somehow became more universal. The actor, who, like Branagh, grew up in Belfast, saw much of his own upbringing in Buddy’s tale, but he thinks that the issues the film’s young hero contends with are not anchored in a particular piece of geography.

“As soon as I read the script, I was smacked with memories of experiences I’d had at that age,” he says. “I connected to the souls of these people. This may be Ken’s personal homage to his hometown, but it’s also every boy’s tale of growing up in circumstances that can be happy as well as dark.”

• • •

The pandemic may have made “Belfast” possible, giving Branagh the space and time he needed to put his thoughts on paper and the will to get the movie made, but it has disrupted his professional life in other ways. Two films that he directed before “COVID” had entered the popular lexicon, “Artemis Fowl” and “Death on the Nile,” had their release plans dramatically altered. After multiple delays, “Artemis Fowl,” a fantasy adventure aimed at family audiences, finally debuted on Disney Plus in June 2020, at a time when most theaters were closed. “Death on the Nile,” having suffered similar postponements, is scheduled to sail into cinemas in February 2022, a year and a half after it was supposed to debut. Some filmmakers have been outraged to have their movies premiere on streaming services instead of cinemas (just look at the eruption of opprobrium that greeted Warner Bros.’ decision to release its entire 2021 slate simultaneously on HBO Max). Branagh seems sanguine about “Artemis Fowl’s” fate.

“I was happy that ‘Artemis Fowl’ had a chance to get to a family audience in the middle of a pandemic that needed such an entertainment,” says the director. “These decisions are made in the heat of these ever-changing circumstances, so it’s difficult to be prescriptive about what to do. I can’t complain about it since so many more difficult things were happening to people.”

The delays for “Death on the Nile” have presented different challenges. Since the film was shot in 2019, one of its stars, Armie Hammer, has been accused by multiple women of sexual abuse, something that has triggered an investigation by Los Angeles police. Hammer denies the allegations, but he has been fired from several projects in the wake of the scandal, and it’s unclear if the claims will overshadow Branagh’s film.

“What’s gone on there is a personal and private matter of which I have no knowledge and of which I think is going through a process which has to be respected,” says Branagh. “Those very serious issues are being dealt with seriously.”

As for the film, Branagh says, “It’s a very entertaining movie with a lot of people’s work wrapped up in it. A lot of Agatha Christie fans want to see it. A lot of Hercule Poirot fans want to see it. I’m hoping it gets its day in the sun.”

“Belfast” may represent a professional pivot for Branagh, who has spent much of the past decade overseeing epic Hollywood fare such as “Cinderella” or “Thor.” This marks something of a return to his indie roots. Branagh first caught the public’s attention with his stirring 1989 adaptation of “Henry V,” earning Oscar nominations for lead actor and for his direction, and he’s returned to the Bard with adaptations of “Much Ado About Nothing” and “Hamlet,” among others. Branagh says he’s toying with another oft-adapted Shakespeare play, “King Lear,” but with an important twist.

“I’ve talked with collaborators about a full-length feature animated ‘King Lear,’” he says. “I’m always looking to do Shakespeare in ways that surprise people, and an animated version of that play would be pretty unusual. You could do things with that form that might not have been done before.”

He’s also interested in making smaller-scale films based on original ideas.

“This film has opened up a desire to communicate in a slightly different way as a filmmaker,” Branagh says. “I’ve been extremely fortunate to be involved in some big films over this last decade, and they are great big, amazing machines where there’s a trillion collaborators. There are tremendous advantages to be had from the resources afforded you, but I value the bespoke cottage-industry quality to ‘Belfast.’ That kind of handcrafted product is harder to achieve with big films.”

As for “Belfast,” Branagh insists he’s not handicapping the movie’s Oscar chances. Getting to make the film was reward enough. He’s also received an important endorsement from his two siblings — older brother William and younger sister Joyce. They agreed that he did their family story proud and noted that their parents would have been delighted to have been brought to life by Dornan and Balfe, performers of stunning beauty. But one thing surprised Joyce about Branagh’s choice of material.

“For a very quiet, private man, you’ve really put yourself out there,” she told her brother shortly after the credits rolled.

At one point, Branagh was going to be even more closely enmeshed in the film. The picture was originally going to end with an older Buddy, played by the director, returning to the city where he was born. The actors shot a sequence where the entire family — Dench, Dornan, Hinds, Balfe and Hill — walked down the street that had played such a key role in shaping Branagh’s life and art, accompanied by the filmmaker himself. It ended up getting excised from the final film.

“It just didn’t work,” says Branagh. “Maybe I’m unique in being a director who cuts himself out of his own movie. The good thing was I didn’t have to write the letter, which I usually have to send saying I’m ever so sorry. You were brilliant. It’s the director who got it wrong. You’re on the cutting-room floor. My apologies.”

Styling: Tom O’Dell; Grooming: Emma White Turle/The Wall Group; Image 1: Coat: Timothy Everest; Sweater: Anderson and Sheppard; Image 2 (cover): Coat: Timothy Everest; Shirt: Budd Shirts; Image 3: Coat: Timothy Everest; Shirt: Budd Shirts; Pants: Drakes; Image 4: Coat: Timothy Everest; Shirt: Sunspel

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.