Kenneth Anger, Avant-Garde Filmmaker and Hollywood Fabulist, Dead at Age 96

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Time is all we have and every second that ticks away is one less second we’re alive,” Kenneth Anger told an interviewer from The Guardian 16 and a half years before his death this May at the age of 96. “The sands of time are going through the hourglass but it doesn’t frighten me.”

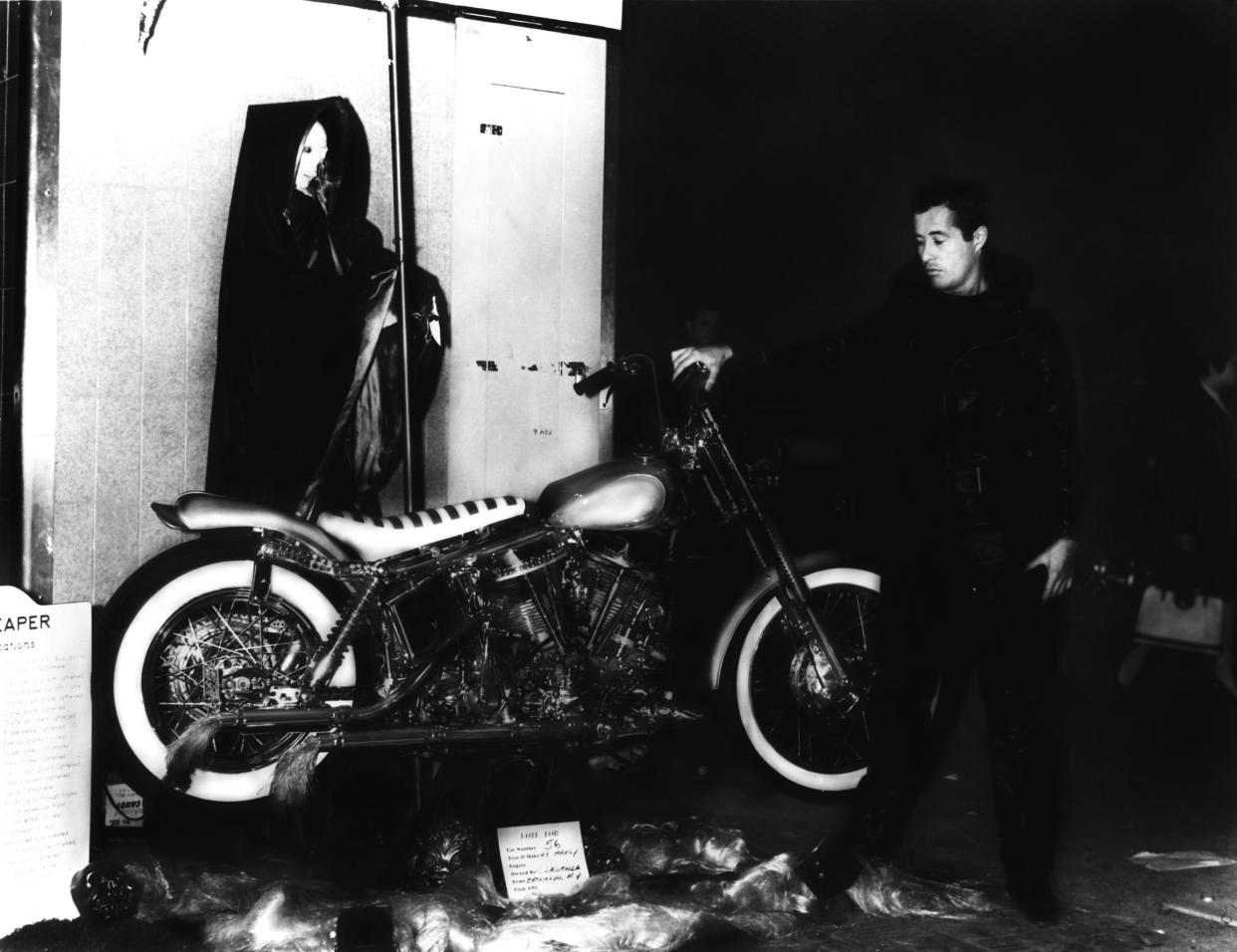

If Woody Allen’s Zelig was found rubbing elbows with the storied and famous of the ’20s and ’30s, starting in the 1950s Anger (born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer in 1927 in Santa Monica, California) was for some decades more than a match for him. His legacy is poised between the pathbreaking cinematic auteur who made such avant-garde shorts as “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” (1954) and “Scorpio Rising” (1963) and the purveyor of at times fictionalized Hollywood scandal in the sensational and frequently updated “Hollywood Babylon” (1959).

More from IndieWire

Angela Bassett on Tina Turner's 'Final Words' During 'What's Love Got to Do with It' Filming

Michael Lerner, Character Actor and 'Barton Fink' Oscar Nominee, Dead at 81

He was not immune from his own brushes with dark history — the very bikers he incorporated in some of his middle-period work would be involved in the blood-stained Hells Angels incident at the Altamont festival (revealed in documentary footage), and he consorted with the musician Bobby Beausoleil, who not only fatally stabbed to death an enemy Charles Manson designated, but during a subsequent prison term continued to work with Anger on soundtracks.

The filmmaker’s fascination with the occult religiosity of Aleister Crowley was reflected in his pulpy book collections “Hollywood Babylon” I and II and its documentary short (1965) and throughout his career under the rubric of his Magick series of experimental shorts. And if the Crowley connection led to extended creative flirtations — thanks to intros by John Paul Getty — with such British rockers as Jimmy Page, Mick Jagger, and Keith Richards (not to mentions the latter’s girlfriends Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg), the more sensationalized anecdotal history should not occlude the creative fount that he was.

Martin Scorsese, arguably the inheritor who did the most lasting and committed work incorporating pop music into films where soundtracks once solely ruled, has long credited Anger as a key inspiration. Robert De Niro advancing through the bar and into movie history at the start of Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” (“Jumpin’ Jack Flash”), David Lynch’s succulent offering of “In Dreams” to set the haunting tone of “Blue Velvet,” and some dozens of evocative pop music cues in Quentin Tarantino’s work arguably would not have come to the fore without Anger’s influence.

The difference between Anger and any number of Hollywood fabulists and mountebanks was that his early encouragement in avant-garde film came via experimental film legend and artist Jean Cocteau, who invited him to France circa 1950. And Anger’s decision to make his addictive Hollywood scandal samplers was encouraged (by his own often-hyperbolic account) by his Cahiers du Cinema mentors François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps the oddest outlier of Anger’s celebrated cohort of visionaries, artistes, criminals, and the simply notorious was sex researcher Dr. Alfred Kinsey, who filmed him masturbating for one of his legendary reports. But just as striking but perhaps more logical given Anger’s deep immersion in (mostly male-on-male) erotica, is the appearance of novelist Anaïs Nin, doddering through the hallucinatory, transgressive episodes of “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.”

Puck Film Prods

It could be easy, in cataloging Anger’s many famous connections, to lose sight of what critic Dave Kehr identified when Anger was more active: “Andy Warhol aside, Kenneth Anger may be the United States’ best-known maker of experimental and avant-garde films… The missing link between Caravaggio and Bruce Weber, Mr. Anger continues to astound and delight with imagery so luxuriant and mysterious that at times it feels almost frightening.”

If subsequent to his advent Anger’s aesthetic would be reflected in such flamboyant eruptions as Jack Smith’s “Flaming Creatures” (1963) and Mike Kuchar’s “Sins of the Fleshapoids” (1965), he was likelier to cite his influence on Stan Brakhage. And if Anger’s exploitations of the industry’s sordid tales implied judgment, he was equally an autodidact of mainstream Hollywood history even as he was part of it. He claimed to have appeared as a boy in William Dieterle and Max Reinhardt’s Warner Brothers fantasia “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in 1935, and his searching eye led him to recast the medium’s early technological quirks from the days even before talkies appeared.

Such works as “Fireworks,” “Rabbit’s Moon,” and “Eaux d’Artifice” glow — especially in restored versions done by the UCLA Film Archive in service of updating his oeuvre — with the shiny surfaces of 1920s nitrate film. For nighttime scenes, again as a deliberate callback to the silent era, Anger incorporated that period’s deep blue tints. He would move on with homages to the near-repetitive use of color that Douglas Sirk and other Technicolor masters commanded. In a nod to his grandmother’s history as a studio wardrobe designer, his “Puce Moment” features a wildly vibrant array of dresses.

It’s hardly unusual for a trailblazing artist to arise from bourgeois roots, but Anger is certainly one. His family’s Midwestern Presbyterian roots offer no clue as to his later immersion with the occult. His father Wilbur’s job as an electrical engineer with Douglas Aircraft enabled a comfortable life for the family (Kenneth being the third-born) until the Great Depression joined with Kenneth’s stature as the troubled family member who would spend more time with grandmother, Bertha, who took him to see a double bill of “The Singing Fool” and “Thunder Over Mexico” and supported his early artistic instinct. He has said, “I was a child prodigy who never got smarter,” but aligned with his interest in film — he claimed to have made his first film at age 10 — was the chance to mingle with such child stars as Shirley Temple at the Santa Monica Cotillion.

He would rush into his life’s work soon enough in any event. At 20, he made the film that attracted the attention of Cocteau (Anger would claim he made it at 17). The 14-minute film “Fireworks” (1947) was shot during a single weekend while his parents were out of town.

Much of the Anger visual imprimatur is already in place in it: murk and shadows, almost phantom images appearing only to fade away, and, even more evocative of his later tropes, several male sailors appear to forcibly sexually assault a bystander, played by none other than Anger drenched in milky fluid. In what would set the tone for his entire history to come, the film saw an almost covert circulation following its 1947 premiere at L.A.’s Coronet Theater. Some years later the LAPD vice squad raided the Coronet, confiscated its copy of “Fireworks,” charged the theater manager a fine, and put him on three years’ probation for violating the obscenity statute in the Motion Picture Production Code.

Moving to Europe, Anger produced a number of other shorts inspired by the artistic avant-garde scene on the continent, such as “Eaux d’Artifice” (1953) and “Rabbit’s Moon” (released almost two decades later in 1971). He came to a wider recognition, or at least notoriety, with “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” (1954), “Scorpio Rising” (1964), “Kustom Kar Kommandos” (1965), and the much-derided, and also widely circulated, “Hollywood Babylon” (1965). His absorption in the Crowley demi-monde led to various works centered on the mystic’s Thelemite belief system, including “Invocation of My Demon Brother” (1969) and “Lucifer Rising” (1972). More famous than financially supported, Anger couldn’t raise production money for a sequel to “Lucifer Rising,” despite nurturing the dream through the mid 1980s. Out of some despair and the need for cash, he quit filmmaking to bring forth the book sequel “Hollywood Babylon II” (1984). In January 2019, podcaster Karina Longworth launched 19 episodes of podcast “You Must Remember This” devoted to researching and mostly debunking the contents of Anger’s “Hollywood Babylon.”

In more recent years Anger lived the part of a respected if underfunded doyen of cinema as art. Speaking to a cineaste site in his latter days, he still carried the mantle of a Hollywood maverick who nonetheless carried a deep love for the town and the medium he so boldly influenced: “I loved the young John Wayne. ..that’s a little slice of history. I love the things that have gone by the wayside.”

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.